Setting Verdi’s opera in the era of the suffragettes’ campaigning and

Edward Elgar’s paean to ‘Englishness’ - the composer’s symphonic study Falstaff Op.68 was premiered in 1913 - neatly promotes pertinent

‘issues’ but also dilutes, a little, the immediate comic impact of the

out-size peer of the realm, Sir John Falstaff.

Designer Giles Cadle has been eager, it seems, and unlike the opera’s

eponymous protagonist, to stick within his budget. While Falstaff is

pestered in his attic garret by a gothic, disembodied hand which thrusts an

unpaid bill - for “Six chickens: six shillings. Thirty bottles of sherry:

two pounds. Three turkeys ... Two pheasants. An anchovy ...” - through the

floor boards, Cadle presents us with a cardboard cut-out set which allows

us to take in a long and short perspective of Windsor’s castle and forest,

and to enter some interior dwellings.

We begin in Sir John’s sparse abode above the Garter Inn. The pseudo-grand

double-arch proscenium frame (a nod in the direction of William Tite’s

multi-arched entrance to Windsor & Eton Riverside Railways Station,

perhaps) and the sharp perspective retreat of the central raised, square

platform seems to mock the pretentions of the Knight’s former glories, as

embodied by the portrait of a slightly more svelte Falstaff in Hussar

uniform which leans against the military hut from which the aging knight

bursts with vitality and vulgarity.

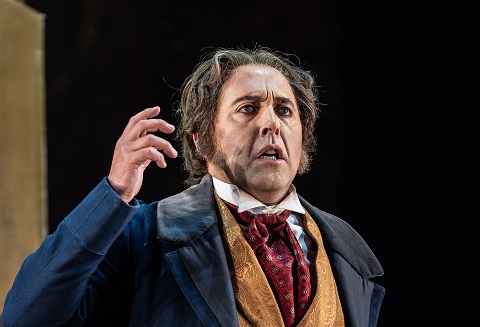

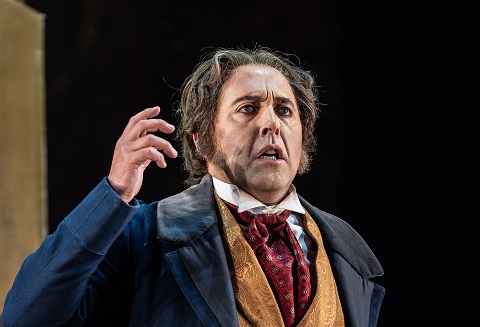

Henry Waddington (Falstaff) Nicholas Crawley (Pistola) Adrian Thompson (Bardolfo) Ansh Shetty (Page). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Henry Waddington (Falstaff) Nicholas Crawley (Pistola) Adrian Thompson (Bardolfo) Ansh Shetty (Page). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

This is a world in which feudalism has given way to the top hats sported by

the worthy professionals of the nineteenth-century middle classes, such as

Dr Caius, who is unceremoniously duped and turned on his head - literally,

in the opening scene - and the bowler hats of the up-and-coming lower

orders, such as Pistola and Bardolpho, who hedge their bets with regard to

where their allegiances and labours are best bestowed. The only servant

upon whom Falstaff can depend for loyalty is the young urchin who’s happy

to share a tankard and to do his ‘aristocratic’ master’s bidding - and to

dress up as a somewhat ‘benign’ Grim Reaper in the final scene.

Cadle utilises a rolling backdrop to set the scene. First, we have a vista

which takes in the Thames (in which Falstaff will take an unanticipated

dip, courtesy of the ladies whom he courts) and the castle of Windsor

(loosely based on Turner’s

Windsor Castle from the Thames

c.1805). Next, we are whisked to Tite’s spacious railway concourse, the

platforms of which retreat graciously and extensively under elegant arching

ceilings.

Here, the female members of the Temperate Society gather, bearing banners -

‘Lips that have touched liquor shall not touch ours’ - while Suffragettes

reminds us that only ‘Convicts, Lunatics and Women! Have No Vote for

Parliament!’ The political activity does not seem to bother the inscrutable

ticket officer ensconced in his tiny office; in fact, the dramatic focus

seems to be on the charms of the steam locomotive that will chug and puff

its way across the stage, raising a chuckle or two - and the only dramatic

function of this locale seems to be that it provides a little Brief Encounter sentimentalism for the romantic embraces of

Nannetta and Fenton.

Hollie-Anne Bangham (chorus) Victoria Simmonds (Meg) Yvonne Howard (Mistress Quickly) Soraya Mafi (Nannetta) Mary Dunleavy (Alice Ford). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Hollie-Anne Bangham (chorus) Victoria Simmonds (Meg) Yvonne Howard (Mistress Quickly) Soraya Mafi (Nannetta) Mary Dunleavy (Alice Ford). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

When Falstaff is duped into paying a call to Alice Ford, he finds himself

amid Victorian flock wallpaper and screens, and faux foliage. The allusions

to the detective fiction of the 19th century -the clumsy

detonation of the screens by Ford and his accomplices, à la

Holmes’ fictional foil, the police inspector Mr Athelney Jones - feel

rather perfunctory, just as Falstaff’s secreting of his bulk in the laundry

basket seems a bit laboured, especially as on this occasion he appeared to

get ‘stuck‘ as he slides unceremoniously into the murk of the Thames. The

result is laughs of the glibbest kind, such as those derived from the

assault on Meg’s ‘innocence’ when the Knight, who has gleefully divested

himself of his underwear when donning his tartan and sporran in

anticipation of sexual high jinks, flashes his nether regions at a

delighted/disconcerted Meg.

Cadle’s design reaches its apotheosis in the final Act: the menacing

foliage which creeps in right and left threatens to swallow the evening

forest tryst - à la Richard Dadd - and Falstaff himself is hoisted

aloft, as a sort of Maypole exhibit, an image which is both cruel and

comic.

Henry Waddington (Falstaff) and GPO Chorus. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Henry Waddington (Falstaff) and GPO Chorus. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

But, set and design and aside, most of the enjoyment comes, as it should,

from the singers and players. The Philharmonia Orchestra serve up

tip-toeing instrumental delicacies and brash quasi-vulgarities with equal

splendour, under the baton of Richard Farnes. If the coloristic orchestral

onslaught is not always sensitive to the needs of the singers and there are

moments when the vocal lines struggle to fight for space to be heard, then

Farnes is ultra-alert to the ever-changing moods and tempi.

At the centre of the music-drama is Henry Waddington’s Falstaff: a figure

who is wide of girth, proud and assured of his ‘entitlement’, but also

surprisingly sensitive of spirit and judicious of vocal articulation of his

self-worth. Falstaff’s ‘honour’ aria was eloquently delivered - how

pleasing it was to have time to take in the words and their sentiment,

particularly when they are so thoughtfully delivered with expressive nuance

- and perceptively accompanied, and it made its mark. In contrast, the

Knight’s lamentations about the sorry state of the world at the start of

Act 3 did not quite have sufficient space within the accompanying

instrumental medium to penetrate with sufficient pointedness. But, this was

a Falstaff who wanted us to think, rather than guffaw, and that’s no bad

thing.

Richard Burkhard (Ford). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Richard Burkhard (Ford). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Richard Burkhard’s Ford was a compelling figure of rage and revenge, and

his vendetta aria, ‘È sogno o realtà?’, conjured real threat and menace. I,

for one, wouldn’t want to cross him. As his wife, Alice, Mary Dunleavy was

a bright star, evincing smile-inducing guile and girlishness, complemented

by intelligence and ingenuity - all conveyed with vocal assurance and

plushness of sound.

Victoria Simmonds’ Meg Page was fittingly uptight, with an undercurrent of

mischievousness; Soraya Mafi’s Nanetta and Oliver Johnson’s Fenton reminded

us that there are real human emotions and lives at stake.

Soraya Mafi (Nannetta). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Soraya Mafi (Nannetta). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

The only downside of this direct and compelling production was the

unanticipated and unwelcome intrusion of the hedonist thumping and twanging

of a nearby pop concert, carried by the brisk wind from outside the Wormsley

estate to the opera pavilion, which, in particular, marred the magic of

Soraya Mafi’s nocturnal serenade. Goodness knows what the Fat Knight would

make of such a discourtesy.

Claire Seymour

Verdi: Falstaff

Sir John Falstaff - Henry Waddington, Alice Ford - Mary Dunleavy, Ford -

Richard Burkhard, Meg Page - Victoria Simmonds, Mistress Quickly - Yvonne

Howard, Nannetta - Soraya Mafi, Fenton - Oliver Johnston, Dr. Caius - Colin

Judson, Bardolfo - Adrian Thompson, Pistola - Nicholas Crawley, Page

(silent) - Ansh Shetty; Director - Bruno Ravella, Conductor - Richard

Farnes, Designer - Giles Cadle, Lighting Designer - Malcolm Rippeth,

Movement Director - Tim Claydon, Philharmonia Orchestra & Garsington

Opera Chorus.

Garsington Opera Festival, Worsley; Saturday 16th June 2018.