Metropolitan Opera 2017-18 Review – Roméo Et Juliette: Ailyn Pérez, Charles Castronovo, Plácido Domingo & Co. Deliver Darker, Heavier Interpretation of Gounod Opera

By David SalazarGounod’s “Roméo et Juliette” is arguably the composer’s best work – an extended love duet with beautiful melodies that capture the essence of Shakespeare’s classic tale, if not its complexity.

For years, the Met showcased a production that did draw closer to the greatness of Shakespeare, before replacing it with Bartlett Sher’s current interpretation. Sher’s version gets the job done adequately, the massive stage design by Michael Yeargan created in such a way as to have every single scene play out in the space, necessitating only the entrance and exit of props between acts to fill out the mise-en-scene. It is not necessarily the most elegant of compromises as watching supers carry props onto the stage to set it up can detract from the dramatic immersion. In the orchestra, the space looks more or less occupied, but in the family circle the massive gaps in space add to an overall feeling of an unfinished vision; while Sher is not the most dynamic of directors, this disparity in creating productions that are aesthetically pleasing for all areas of the cavernous Metropolitan Opera seems to be the great challenge of every director, with few actually succeeding fully.

As noted, the staging is adequate enough to mount the opera (though a far cry the previous production with its exquisite perspective), and ultimately, this work depends on the strengths of its musical contributors.

Two Lovers With Darker Edge

In the two leads of the opera – tenor Charles Castronovo and soprano Ailyn Pérez displayed great chemistry together. Castronovo was called in last second to replace an ailing Bryan Hymel in a role that he had not sung in five years. Per his own admission, Castronovo had to relearn the part in three days. He didn’t make it to the opening, but he was there on Friday.

Castronovo certainly looks the part of Roméo with dashing looks and physique. He moved about nimbly, portraying a young man with a sense of composure and confidence one would expect of a romantic hero like Roméo. He had a delicate manner with Pérez, from their first interaction to the very end. He also managed to give Roméo an emotional turmoil, best exemplified by a poignant breakdown during the orchestral introduction that precedes the Act four duet. And while his physicality certainly made the interpretation immersive, his darker timbre made him seem far older in age than the teenage years of the character in its original conception. It took some time to adjust to and ultimately, one came away with great admiration for Castronovo’s middle register, which was his sweet spot the entire night.

The famous aria, “Ah leve-toi soleil” was ponderous in approach, the tenor’s darker timbre and slower tempo giving the aria a more introspective feel. The only moments where the voice poured out its full potential was during the B flats on “Parait,” the first of which didn’t seem all that comfortable for the tenor. However, his voice bloomed by the final one, which he diminuendoed from a forte sound. Also worthy of note is that he opted for bringing some high notes down, including the optional high C at the close of the Act three concertato.

But the most important thing about his performance is that both vocally and physically, he shared great chemistry with Pérez.

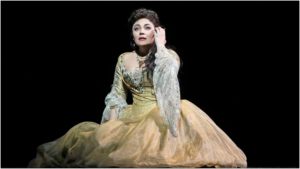

The soprano was once THE Juliette of the opera world, but her voice has transformed into something far weightier that doesn’t necessarily fit the concept of a young girl. The beauty of this opera is that Juliette’s journey is the most delineated and the best sopranos can transform her from an innocent child into a mature woman in control of her destiny. Pérez is definitely in the upper tier of opera stars around the world and manages this development, her strongest singing coming in the second half. She manages the opening aria, “Je Veux vivre” well, the tone vibrant and sparkling on the high B flat from which the opening passage descends. The coloratura passages aren’t as crisp as they once were, but the high As and B flats littered through the aria are confidently sung and the vibrancy of tone matches the overall conception of Juliette as a girl. Pérez’s own movements, graceful and nimble, add to this sense. It’s quite revealing to see how she interacts with Paris and then with Roméo. With one, she moves away, pays minimal attention, and when she does, she just toys with him. But with Castronovo, Pérez’s body took on poise and elegance – she gave off the impression of a secure woman.

The poison aria, Juliette’s other major solo moment, was Pérez’s finest dramatically and vocally. She let her voice blast through the Met with tremendous assuredness, the A trill to the high C delivered with an exciting crescendo that expressed the sense of strength of this Juliette. The middle section of the aria, wherein Juliette questions the plan, was sung with more hushed tone, drawing a contrast with the confident quality of the first section. But the reprisal of the opening section was delivered with even greater vocal force, Pérez’s voice beaming into the theater powerfully.

One note on the two lovers in their interactions with one another. Their voices melded together quite well. Pérez’s volume resonates more firmly in the Met than Castronovo and her weight potentially drowns his out in the more potent musical outbursts. But the two, despite minimal rehearsal time, were there to support one another, the vocal divergences coalescing into a whole, especially in the first and the final duets of the evening.

Alpha Males

Baritone Joshua Hopkins and tenor Bogdan Volkov complemented one another well as Mercutio and Tybalt respectively, both playing up Alpha male interpretations of their respective characters. While this is certainly something one might expect from a Tybalt, sung by Volkov with forceful but elegant sound, it isn’t always the case with Mercutio, who often gets played as a relaxed trickster. But Hopkins really played up his leadership qualities, singing with a ferocious and potent sound that was both gorgeous and intimidating all the same. This played especially well in the scenes where he confronts Tybalt over insulting Roméo, the fight between the two men given greater weight by their genuine battle for control. Of course, a muscular interpretation downplays some of the lighter moments in the opening act when he encourages Roméo to overcome Rosalinde. His Queen Mab aria, while beautifully sung through and through with a luxurious tone and pinpoint intonation, could have used a bit more lightness and overall variation in the tonal colors and dynamics. The phrase “Elle fuit, elle passe” gets repeated numerous times, in alternating quarter and eighth notes to provide the corresponding sense of lightness of the text. Hopkins’ robust sound in these passages was not quite light or fun as it was commanding and pointed. It’s a unique interpretation of the character, adding a darker overall edge to the tragedy.

Light On Lightness

As Capulet, Laurent Naouri provided a balanced reading of the character. The first act emphasizes his joyous nature while the second half features him severe and imposing. The opening sections of the opera saw his voice bright and forward, the sound carrying lightly into the theater and giving off a sense of benevolence and whimsy. But when he confronts his daughter in the second half of the opera, his voice had a snarl, the consonants sharp and jagged, the phrasing pointed with coarser sound. This was anticipated in the previous scene in which his physicality toward Castronovo’s Roméo provided stark contrast to the buoyant and jumpy manner of the opening act.

As the other father figure in the opera, Kwangchul Youn imbued Frère Laurent with contrasting emotional range as well. He had sarcasm and good cheer in his opening scene with Roméo, his grave line phrased with lightness. But then he turned stern and severe during the marriage scene, the bass sound forceful. When he finally relented and agreed to marry the two, he shifted yet again into a lighter tone, this one brighter. For the final scene with Juliette, we got a mix of this stern forcefulness with a gentler touch, the body language poised and concrete.

As Gertrude, Maria Zifchak’s was a force, holding her ground as she snapped at the Capulet bullies, her voice projecting with sharp accentuation. Even though there was tenderness in her approach to Juliette, she still retained that pointed phrasing, emphasizing her protective nature.

As the page Stéphano, mezzo Karine Deshayes took on an aggressive approach to the aria, the octave leap between Fs on “Belle” and high A’s on “tourterrelle,” pushed out to the point that they didn’t quite ring into the hall. The aria as a whole features lighter writing through eighth notes and triplet sixteenths; there was a great deal of accenting in the line, the connections between the lines not always fluid. The overall effect was hints of violence instead of grace, a creative choice which was better suited to the reprisal during the confrontation with the Capulet bullies. There is came off as an intimidation tactic, the prickly phrasing expressing the sense that the character was fighting back against his aggressors. Again, while rather unusual, it coalesced with the choices that Hopkins made with his Mercutio.

Working Hard For Unity

In the pit, superstar Plácido Domingo worked his hardest to keep it all together. His conducting style isn’t for everyone, the maestro substituting unpredictable passion for precision, though in this case, his overall reading of the score was more relaxed in its overall volume, even if it tended to be weightier in its accompaniment of the singers. The Met Orchestra, which is capable of engulfing the auditorium with luminous sound, was far more restrained in that department, never really rising above a mezzo forte. Domingo seemed more interested in offering a pedestal for his singer’s voices to rise above, and given the circumstances it certainly made sense. Some of the choices were unique, such as a pesante feel in many of the dances.

It ultimately made for an unusual experience of Gounod’s greatest opera, laden with a darker edge, the lightness of Shakespeare stripped away. It should be interesting to see if it delves deeper into this direction or not.