Shorn of joy, matted with despair, Philip Venables’s 4.48 Psychosis shot to near classic status after its world premiere in 2016. It might have been a damp squib on second encounter. On the contrary, this intense, 90-minute opera, for six women, a dozen instrumentalists and pre-recorded material, was yet more spiky, cogent, witty and elegiac in its first revival, at the Lyric Hammersmith. It is based on Sarah Kane’s play about the unending labyrinth of clinical depression, finished in 1999 shortly before her suicide at the age of 28.

Venables (b1979), the Royal Opera’s first composer in residence, has said he chose to make an opera from 4.48 Psychosis in part because of his response to the musicality of the text. With so much else to take in when the work was new, from fragmented narrative and unidentifiable characters to the score’s tight, bright skein of musical styles – now minimalist, now rock, close-harmony chorale, a snatch of Bach, a quasi lute song – the verbal aspect did not take on particular prominence. This time it hit home.

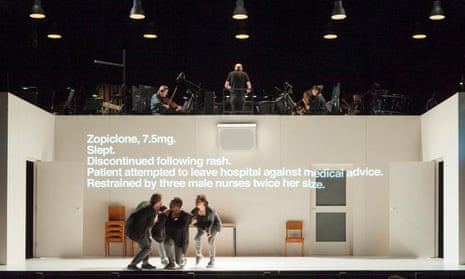

Three sopranos (Gweneth-Ann Rand, Lucy Hall, Susanna Hurrell) and three mezzo-sopranos (Lucy Schaufer, Rachael Lloyd, Samantha Price), all amplified, and with no weak link, express the loneliness and pain of mental illness. There’s enough information to suggest that the 24 short scenes, folding into one another, take part in an institution, but the imprisoning walls and flashing white lights may be of their own imaginings. 4.48 is that time of wakefulness, of lucidity and terror. Venables mixes song with, variously, a spoken voice or words appearing on the rear wall (distinct from surtitles, which are used as needed).

One device he employs to great effect is for a singer to sound the first word of a sentence, on a sustained note, while the speaker completes the rest, as in “I… am fat, I… cannot listen, I… cannot love.” Kane’s own voice is never lost in Venables’s handling.

The production, directed by Ted Huffman, honours the work, with clean, crisp designs, lighting and video by Hannah Clark, DM Wood and Pierre Martin. Richard Baker – like Thomas Adès, Oliver Knussen and Ryan Wigglesworth, a sympathetic composer-conductor – conjured expert playing from the agile musicians of Chroma. With three saxophones, accordion, wood saw, hammer and fist, the score has a dusky, unbleached quality, which intermittently breaks out in lament or cry. The bleakness of the subject matter, and the generosity of the performance, forged to make an unforgettable evening.

The same might be said of the London Symphony Orchestra’s two concerts of Mahler’s final two symphonies, conducted by Simon Rattle and paired, in the case of the Ninth, with a world premiere by Helen Grime (b1981), and in the Tenth with Michael Tippett’s sumptuous late score, The Rose Lake. Grime’s ambitious Woven Space, completing a work in part heard at the opening of Rattle’s LSO season last autumn, had more in common with Tippett’s music than might first appear. His endless twining of canons and song made a resounding echo with the subtle, gleaming intricacies of Grime’s music.

Mahler’s Symphony No 10 (1910), his last, was written not so much in the shadow of death – though it can seem that way, since he died within a year of drafting it – as in the blinding glare of a tormented life. On top of bereavement and his own fragile health, he discovered that his wife, Alma, was having an affair with the architect Walter Gropius. Littering the score with cries from the heart – “To live for you, to die for you” – Mahler established the melodic and harmonic arguments, but much remained incomplete. Some conductors prefer to perform only the Adagio, a 25-minute torso, which in mood answers, and challenges, the slow finale of the Ninth. Christian Thielemann has just released a recording with the Munich Philharmonic. Rattle, instead, has long put his faith in the Deryck Cooke “completion”, performing it frequently enough to conduct from memory. It enables us to hear all five movements, harmonically daring and suggestive of new horizons the composer might one day have explored.

Here, as in the Ninth too, Mahler takes the inner mechanisms of the orchestra, particularly the violas and second violins, and puts them in the spotlight. They played magnificently, seconds to the right of Rattle, violas between first violins and cellos. The rest of the strings, the brass, percussion and woodwind, and the many section soloists, gave their outstanding best to an audience who, especially towards the end of the Ninth, seemed to stop breathing. Man (on this occasion) of the match goes to Chi Yu-Mo, who plays the small but powerful E flat clarinet. He hit his shrill, high notes with spot-on intonation, duetting effortlessly with violin or piccolo or flute, ranging in style from klezmer dance to bucolic shepherd to anarchic goat. Lord knows what it does to his diaphragm.

Star ratings (out of 5)

4.48 Psychosis ★★★★

LSO/Rattle ★★★★★

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion