Krzysztof Warlikowski’s new Royal Opera staging of Janáček’s From the House of the Dead, the first in the company’s history, opens with silent but subtitled footage of the philosopher Michel Foucault heatedly discussing the prison system, which he analysed, attacked and attempted to reform throughout much of his life. A startling opening to a radical if flawed interpretation, it immediately exposes the tensions and problems to follow. The footage rolls over Janáček’s prelude, played with ferocious power by the ROH orchestra under Mark Wigglesworth. But reading Foucault pulls us away from the music, and our focus blurs.

Posthumously premiered in 1930, From the House of the Dead derives from Dostoevsky’s autobiographical 1862 novel that drew on his experience as a political prisoner in Siberia. Janáček focuses on Dostoevsky’s idea of the “spark of God” in every human being that has the potential to redeem even the most hardened criminal. There’s little plot as such, and the opera interweaves an unsparing portrait of prison life with multiple narrations, as the inmates tell each other the stories of their lives. It’s a depiction of a living hell in which the idea of heaven is nonetheless present, as a profoundly touching discussion about the gospels – between the political prisoner Gorjancikov and the damaged yet saintly Aljeja – makes clear.

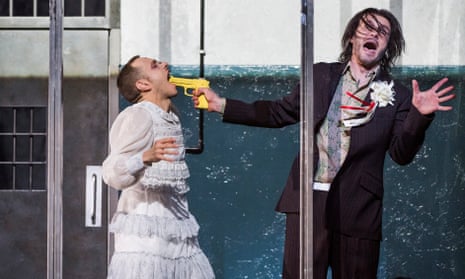

Warlikowski dispenses with Siberia, and relocates the opera to an anonymous modern penitentiary where the Governor scrutinises the prisoners on CCTV and guards surreptitiously supply drugs to the men they brutalise. The atmosphere of incipient violence is powerfully realised, as emotional and sexual frustrations fester, and the prisoners turn on each other as well as their guards. But Warlikowski falters when it comes to the inmates’ narratives by over-elaborating the imagery of the opera’s central scene, in which the prisoners put on plays for each other.

A revolving oblong box that contains the Governor’s office gradually morphs into a stage on which the narratives are obliquely re-enacted. As Skuratov (Ladislav Elgr) tells us how he murdered his lover’s husband, the players’ rehearsal behind him glosses the story. Šiškov (Johan Reuter) and Luka (Štefan Margita) gradually become aware that their destinies are horrifically linked as they play out their rivalry for a woman, which has destroyed both of their lives. The narratives themselves, however, are concentrated dissections of the human soul that have their greatest impact when unadorned. Once again, we’re aware of a crucial loss of focus.

For all that, however, you need to see it, since the performance itself is formidable. Wigglesworth, using John Tyrrell’s new critical edition, prises open every facet of the score. Playing and choral singing are outstanding, and none of the cast, one of the finest Covent Garden has assembled in recent years, puts a foot wrong. Margita and Reuter make Luka’s and Šiškovs’s anguish palpable. The deepening relationship between Willard White’s Gorjančikov and Pascal Charbonneau’s Aljeja is beautifully done. However, perhaps the most striking performance comes from Nicky Spence as the violent Nikita: the closing scene, in which he finally helps and befriends a prisoner he has previously attacked and injured, heartbreakingly captures Janáček’s faith in humanity even at its darkest, and will linger long after the curtain has fallen.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion