Approaching any of the various versions of Boris Godunov, one knows to expect a bleakly nihilistic evening. The blood-boltered history of Russia stretches like a despairing road from the horrors of Ivan to the modern monsters of Stalin and Putin and this opera, more than any other work, vividly conjures a society lurching between tyrants and opportunists. Mussorgsky’s original version lacks even the leavening yeast of the sensual and corrupt Polish court or the brightness of any substantial female roles. It is hardly surprising that it was sent back by an uncomprehending management with the demand that the composer added at least one prima donna role.

But, despite these perceived difficulties, the work shines prophetically forward to the masterpieces of Shostakovich and Prokofiev. It also stands as one of the great company operas providing a cornucopia of small but rewarding roles. Although a great Boris should be the impetus for mounting the work, the company must also field numerous other strong, low voiced singers. And, on top of that, a huge chorus to portray the various strata of oppressed Russian society.

The Royal Opera has a rich and honourable history of performing this work, stretching back to Shalyapin, Silveri directed by Peter Brook through to Robert Lloyd and John Tomlinson directed by Andrei Tarkovsky and memorably conducted by Abbado and, later, Bychkov.

This new production was conceived around Bryn Terfel’s first Boris and Antonio Pappano’s first time conducting the score. Richard Jones has had many successes with both Pappano and Terfel – his Meistersinger with Terfel at WNO remains one of the most memorable and successful. There was much to admire in his determinedly un-romantic approach – Jones’ Russia is a grim, dangerous place. He got much right – the disorganised panic of the Boyars as they try to cajole Boris towards the throne was perfectly done and eloquently evoked the chaotic process of succession in Russia, so well described in Simon Sebag-Montefiore’s recent history of The Romanovs which commences with the rise of Boris. But some of the stage mechanics is distinctly juddery, complete with thudding flats and vocal noises off. Much of this stemmed from the laudable intention to run the opera without a break – unfortunately there are moments which would have been much more effective with the use of a curtain or front cloth to cut off the end of the scene. Worst among these were the undignified scramble for the wings at the end of the Coronation Scene and the climax of Boris’ hallucinatory terror at the end of Scene 5 which left Terfel to slope off in semi darkness. Nothing here equalled the sight of Robert Lloyd’s terrified Tsar tangled in the huge map of his domains in the Tarkovsky production.

Worst was the continual re-winding of Dimitri’s murder. Because the murder was stylised, with Dimitri masked and looking more like a doll, it wasn’t remotely the horrifying event it should be (although the ROH, no doubt mindful of some of the sensitive flowers amongst its audience, saw fit to print a warning about the onstage murder). Hints at the edge of the audience vision are often so much more effective than overt portrayals. Projection is an overused medium in opera but in this case it could have provided something far more subtle and terrifying. The endless repetition of the same visual motif quickly became tiresome, particularly as the work doesn’t need this literalisation.

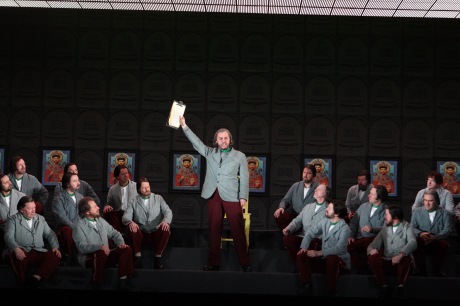

Whatever reservations concerning the production, there is no doubt the Royal Opera did the work proud in terms of casting. First, a word for Renato Balsadonna‘s wonderful chorus work. They duly pinned us to our seats in the first two scenes and later, as the poor outside the cathedral. In this version they don’t get much of the fun acting, deprived, as they are, of the Kromy Forest scene and the Polish Act, but they grabbed all opportunities on offer with both hands. As with their beleaguered colleagues in St Martin’s Lane, they proved that the chorus is the core of an opera house. Undervalue it at one’s peril.

The orchestra under Pappano was in similarly world beating form – the astonishing Coronation Scene was barbaric in splendour with the bells pealing out to almost nightmarish effect. Pappano showed that even this moment of apparent triumph is stained with guilt and blood. He also ably pointed Mussorgsky’s subtle use of themes and variants on them – I had never noticed so clearly that the scratching motif which opens Pimen’s monologue is a quiet drawn out variant on the oppression theme which opens the opera – Pimen is writing of past horrors so the theme is distanced and semi-submerged.

Terfel’s Boris was haunted even from the moment he was informed of Dimitri’s murder – for once one really believed him when he refused the throne. There is no record of whether Mussorgsky was familiar with Shakespeare but the parallels with Richard III and Macbeth are almost irresistible. Also noticeable is allusion, unconscious or otherwise, to Henry IV’s anguished “God knows, my son, by what by-paths and indirect crook’d ways I met this crown..” in Boris’ farewell to Feodor. Vocally, Terfel is some way removed from the black-voiced Slavs of tradition and the very lowest parts of the role are currently a stretch for him. But after a muted Coronation aria, possibly not helped by his positioning on the upper enclosed section of the set, his portrayal grew in power and subtlety. The big monologues were both well done, as was his harrowing vocal disintegration at the climax of Scene 5. The farewell to his son was memorable as much for the way Terfel fined his voice down to a whisper as his life ebbed away. He crowned the scene with a roaring “I am still Tsar” before collapsing into his last mumbled “Forgive me, forgive me”. A memorable role assumption which will grow in stature with further performances.

Equally striking was the dark voiced Ain Anger making his debut as Pimen. The long scene with the forceful Grigory of David Butt Philip, which can often seem tedious after the splendour of the prologue, was riveting from beginning to end. Butt Philip made much of the role of Grigory but there’s no disguising that the role is an unrewarding task without the Polish and Kromy scenes. He was also saddled with a horribly unflattering costume and wig. Indeed, unflattering costumes seemed to be the order of the day with the Boyars seemingly fallen on very straightened times and Shuisky dressed as an orderly from one of the less glamorous foot regiments. Only in the riot of colour for the Coronation scene was the richness of the court evoked.

Varlaam is about right for Sir John Tomlinson these days and his rollicking performance went some way to banishing memories of his Marke last season. He formed a hilarious double act with Harry Nicoll’s excellent Missail, who played a mean set of spoons as well. Rebecca de Pont Davies added to her gallery of eccentrics with a beady eyed Hostess of the Inn.

I wish I could be as enthusiastic about the usually excellent John Graham-Hall’s Shuisky, but, partly hampered by the production, he came over as fatally muted both in character and voice. Shuisky needs a tenor with plenty of sap in the voice – this performance did little to banish memories of Philip Langridge’s superlative assumption.

Fortunately the other parts were of high standard with special mention of Kostas Smoriginas excellent as Shchelkalov (what a gift of a role this is!) and Vlada Borovko as Xenia. The role of Fyodor, usually assigned to a mezzo, was taken by a boy treble in this production. While Ben Knight gave a moving performance as the doomed Tsarevich, there were moments of inevitable imbalance against other voices. Possibley a subtle amount of amplification might be wise. Andrew Tortise gave us a beautifully sung and poignant Holy Fool. I do wish though, that his hat had been the proper tin variety instead of what looked like an inverted plastic bin.

Despite reservations regarding the production, this is a worthy vindication of Mussorgsky’s original, pitch-black vision of Russian history. Warmly recommended.

4 stars

Sebastian Petit

(Photos : Catherine Ashmore)