Emmanuel Chabrier had many gifts – though any kind of formal musical education wasn’t among them – but the one thing that impresses most about his brief, incident-packed life (dead at 53, from syphilis, in 1894) is the simply staggering roll-call of people who counted him as a close friend, including Renoir, Manet, Degas, Monet, Verlaine, Mallarmé, Zola, Fauré, d’Indy and Chausson. He came from humble Auvergne stock – and looked it too, being thick-set and short – and only really became a full-time composer in 1880, when he resigned from his day-job as a civil servant, aged 39. For the rest, he had taught himself composition and orchestration by copying out Wagner’s Tannhäuser in full score, and sedulously reading Berlioz’s Grand traité d’instrumentation et d’orchestration modernes. Yet such was the regard in which he was held by so many, not least in his own chosen sphere of music – Debussy and Ravel both adored him, Stravinsky and Satie professed themselves his debtors – that the man who had never even been to any of the Parisian grands écoles de musique, let alone won the coveted Prix de Rome over which all other would-be composers fought like cats in a sack, was eventually appointed Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur. Alas, though he had the gift of friendship in spades, in all other respects he was the unluckiest man alive, and it somehow seems typical that his two finest operas both had successful premieres only for Brussels’ La Monnaie – Gwendoline, 1886 – to close after two performances due to bankruptcy, and the Opéra Comique at the Salle Favart – Le roi malgré lui, 1887 – to burn to the ground within the week.

L’étoile, written to a libretto by Eugène Leterrier and Albert Vanloo (who’d already collaborated with Offenbach on his Le voyage dans la lune for the very same theatre, the Bouffes Parisiens, in 1875) was first performed in 1877 and only enjoyed very limited success. Nor did it travel well thereafter – London only heard it for the first time in 1899, at the Savoy, wholly re-written as an English musical: the performance tonight marks its Covent Garden debut – and the piece effectively vanished until the Opéra Comique staged it in Nazi-occupied Paris in 1941. The real turning point in the opera’s fortunes came in 1985, when it was mounted at both the Salle Favart in Paris, and the Opéra de Lyon, the latter conducted by John Eliot Gardiner (and both recorded by EMI and filmed). More recently, the Opéra Comique has had another crack at it – in 2007, with Stéphanie d’Oustrac – and no less than Simon Rattle conducted it at the Berlin Staatsoper in 2010, with Mrs. Rattle in the trouser role of Lazuli. Now we have – apparently in co-production with no-one (!) – the work’s belated London premiere, directed by Mariame Clément and conducted, in the fortieth anniversary of his house debut, by Mark Elder.

To be honest, I didn’t entirely approach this event with equanimity. People I know were at the dress rehearsal on Friday and all came back with various gripes and grievances, the most universally-expressed of which was horror at the introduction of two new speaking roles, taken by actor/comedians, who both comment upon and interfere with the action of the opera proper, taken by Chris Addison (whom I’m apparently supposed to have heard of) as “Smith” and Jean-Luc Vincent as “Dupont”, speaking in English throughout whilst the rest of the piece goes its sweet way in the original French. O God, I thought, here we go again! Take a delicate, unfamiliar work and proceed to grind it into the ground with directorial overkill and smart-arsery, betraying a complete lack of faith in the opera itself and the possibility than an audience just might, mind, might manage to appreciate a work on its own terms without being spoon-fed and/or truckled to. And judging by the pretty tepid response tonight, and a vague sense I had around me of somewhat stern critical disapproval, then you might well imagine that the unimpressed party has indeed carried the day.

Except for the fact that, try as I might, I couldn’t summon either outrage or upset at the manner of the opera’s presentation, and indeed sat there thinking that the set designs by Julia Hansen were absolutely exquisite, and exquisitely realised in myriad, complex Pollock’s toy theatre-type detail. I didn’t even mind the actor/comedian interventions, because the plain truth is that, apart from getting a dumb-show of late Victorian Anglo-French breakfast manners all to themselves during the four minute overture, their actual contribution to the remaining 45’ of Act I is two minutes of befuddled plot re-iteration of the “well who is this, and why are they here?” variety, less than a minute in Act II and nothing at all in Act III other than – disguised as Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson – resolving the plot, which by that time no-one can either remember or care anything about anyway even if they do. Do they need to be there? No. Do they add anything much? Not really. Is their self-penned dialogue thigh-slappingly hilarious? Dear me, no. But do they get in the way or impair the performance? Not at all. And Chris Addison, whoever he is, actually has a nice line in gangling primness, which could be charitably thought to set up at least a frisson of dramatic contrast with the otherwise generally louche goings-on in the opera itself, all extra-marital affairs, mistresses and ooh-la-la smut. (The plot concerns King Ouf’s reluctance to execute the pedlar Lazuli chosen for the annual human sacrifice-by-impalement having been told by his Astrologer that he’ll only outlive his victim by 24 hours, and thus needing to keep him alive, even though Lazuli is in love with Laoula, the King’s betrothed; but the King has been tricked into thinking that she is actually Aloès, the wife of Tapioca, who really is having an affair with the real Aloès, who’s actually the wife of Tapioca’s employer, Hérisson de Porc-Epic, the matchmaking ambassador of Laoula’s father, King Mataquin, who doesn’t appear. Wozzeck this isn’t).

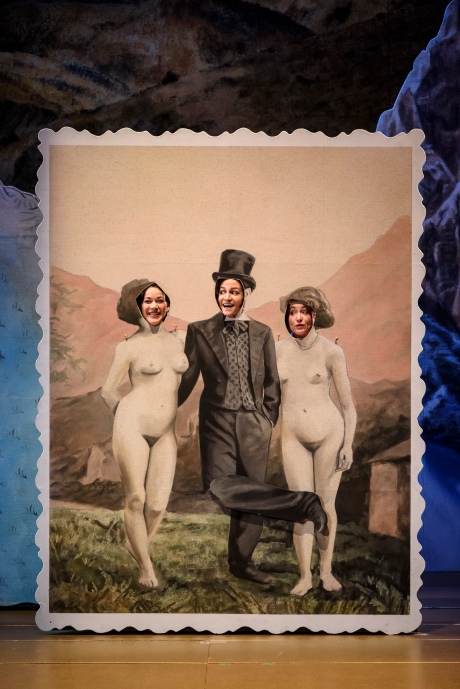

Clément opts to treat the whole shebang in a manner very similar to the House’s stagings of La fille du régiment and, in particular, Il turco in Italia, with mostly flat, parti-coloured painted scenery either flown or slid into position and a substantial reduction in the usable stage space, virtually all of the main operatic narrative happening upstage behind a false proscenium (with a gorgeous, faux Byzantine Persian front-cloth) which must do wonders for the sightlines in the sides of the house, but which I do rather worry might affect basic vocal audibility in the auditorium’s further reaches. Only the interpolated comedian characters get to occupy the foreground shallow framing box with any regularity or duration, though “Smith”’s Chesterfield gets to see plenty of action, on and off. To me, it all looks wonderful, and the arrival of M. Porc-Epic’s party in a hot air balloon emblazoned with the name of the department store they all purport to work for (the fictional Au Bonheur des dames, courtesy of Emile Zola, though the opened-up interior is plainly that of the very real “Galeries Lafayette”) is a sight to see. The worst I could say is that the silly end-of-pier head-through-the-hole bathing costume cut-out they use to accompany the delicious “tickling” trio for the two women Laoula and Aloès and the sleeping Lazuli gets in the way and physically prevents any actual tickling taking place. Other than that, it’s a very classy (and pricey) looking romp, and though the comedy runs out of steam in Act III – a delicious duet hymning the joys of the utterly vile green Chartreuse apart – I wouldn’t lay too much of the blame for that at the director’s door.

Musically, L’étoile stands or falls by the quality of its Lazuli and here, again, I suspect I’m going to be the minority opinion in that I think Kate Lindsey disappoints, both overacting and undersinging (just as she did as Cherubino earlier in the season). Physically, she’s right for the role, but tends to the tiresomely hyperactive (no piece of furniture remains unjumped upon) whilst the voice itself strikes me as of no great scale or distinctiveness, with some very thinly-supported attempts at soft singing – though one duly honours the intention – and a pallid, wiry tone that simply needs a whole lot more flesh and fat on it, particularly in the alarming excursions below the stave in the “sneezing” aria at the start of Act III. I can’t help thinking that either of Mmes. D’Oustrac or Kožená would be far preferable in the role, for me at least. And then there’s the King Ouf of Christophe Mortagne, whose prissy posturings as Guillot in Massenet’s Manon managed to mitigate the thinness of his voice, but whose efforts here can’t disguise the fact that he is now at least as much a diseur as a fully-functioning opera singer (which is what the role actually requires: where is Yann Beuron when we need him?). Poor François Piolino, as Hérisson de Porc-Epic, had a middling torrid time of it in the only act in which he gets to sing anything of any significance – the first – with a couple of cracks and other notes that simply refused to materialise at all, only some of which can be blamed on Chabrier’s tendency to write for baritones in the tenor register.

Hélène Guilmette sings the disguised princess Laoula very prettily and with due diligence, though for me the timbre is too similar to that slightly unfortunate authentic French sound of Mady Mesplé, though mercifully less so. I liked Simon Bailey’s Siroco, the court astrologer, though he has little enough to do, and we get no opportunity to bask in the fabulously burnished bass-baritone he fielded here as Leporello last season, easily the best I’ve heard since José van Dam. Julie Boulianne makes a strong impression as Aloès, and Aimery Lefèvre, tall, dark and very handsome, cuts a dash as a convincingly Lothario-like Tapioca (a nearby esteemed critic from a print daily became quite visibly animated when the character appeared in Act II minus his trousers, evidently mesmerised by the size of his voice). In two spit-and-a-drag roles that effectively vanish vocally after Act I – Patacha and Zalzal – the two Samuels on the Jette Parker programme, Sakker and Dale Johnson, were both excellent (though Mr. Sakker, who first made me sit bolt upright as the Second Armed Man in Die Zauberflöte, and has since sung the gruelling tenor part in Das Lied von der Erde wonderfully, should really be spared this kind of activity: his is a natural Wagnerian Heldentenor of amazingly dark, rounded power and heft – you know, like Kaufmann when he actually turns up – and should simply be allowed to get on with developing it).

Mark Elder presides over a reasonably pacey traversal of the score (not something you can rely on with him, responsible in this very house for the most turgid, lumbering, unidiomatic accounts of Elektra, La bohème, Il barbiere di Siviglia and Adriana Lecouvreur it’s ever been my misfortune to have to sit through). This was more audibly the Elder who can galvanise half-dead Donizetti back into life, and with a modestly-sized band he sifted and sorted the textures for maximum clarity and Gallic sparkle, obtaining some very deft playing in the process. Even so, and though I’ve no doubt you will read quite the reverse elsewhere, I don’t think the prime attractions of this new production are actually musical at all, with too much so-so singing where it most matters, notwithstanding the generally intelligible French of a largely Francophone cast. No, apart from the work itself – which in truth would surely be seen to better advantage in a far smaller house, like Glyndebourne – the main pleasure is to be derived from Mariame Clément’s inventive mise-en-scène and the flawless technical address with which it is all mounted (no mean feat: this is a busy, busy show, with something going on scenically the whole time, and it all passes off flawlessly, which is considerably more than could be said for much of the singing). I can’t imagine the ROH will ever revive it – which is a pity, because they could then correct the casting – so if you’ve any interest in operatic arcana in general, or the French repertory in particular, my advice would be to go and see L’etoile while you can.

3½ *

Stephen Jay-Taylor © 2016

(Photos by Bill Cooper)

Funny thing is that Yann Beuron was actually in the audience last Monday ! I saw him !!