Flame-throwers threw, tumblers tumbled, gigantic carnival masks mocked and leered; crowds waved mops and feather dusters, stilt-walkers and jugglers reeled and tweaked and twirled until golden rain showered from the rafters of the Coliseum and the earth moved. (How? Go see for yourself.) Some of us were still peeling plasticated rectangles of gold from our clothes the next morning.

The artist-director-animator Terry Gilliam, for whom size has always mattered – check out his other folies de grandeur, from Brazil to The Zero Theorem – has called Berlioz's Benvenuto Cellini a "clunky and clanky little story". In his mad, heady new staging for ENO, the ex-Python has restored the 1838 work's epic pretensions. Vitally, he has allowed the music – steered at high speed and with white-knuckled authority by Edward Gardner – to share top billing.

Considering the pre-publicity heaped on the director, this was by no means a given. If the production was mesmerising, the chorus, soloists and orchestra were equally spellbinding in their handling of Berlioz's ebullient score. This is restless, relentless music that glitters with dark wit and contains magnificent choruses (such as the insistent Honneur aux maîtres ciseleurs, in praise of master goldsmiths) as well as a flow of richly melodic arias.

Having promised the kitchen sink, Gilliam has delivered enough domestic appliances for a small town, as well as its inhabitants with all their eccentricities and foibles. This parade of humanity is clothed from the dressing-up box of romantic fantasy: now Victorian, now Roman, now old-style rocker, now saccharine Snow White. The set itself, co-designed by Gilliam, is an amalgam of Piranesi and Goya, as if forced through a paper shredder and stuck together again.

Berlioz's youthful and unwieldy work was inspired by the Italian Renaissance goldsmith of the title. In Cellini, the French composer found a worthy match for his own extravagant self-aggrandisement. Both men's outlandish autobiographies make eye-popping reading. In the guise of exploring the tribulations of the artist's life, the opera is chiefly about getting the girl. Cellini is late with a vast statue commissioned by the Pope. In the war of love – his rival is a fellow artist – the goldsmith is nearly hanged and goes into literal meltdown, calling on God to sort him out. Obligingly, he does.

Despite the apparent excitement of the story, almost nothing happens – though in truth the opera is surely of far more weight and consequence than its reputation would suggest. The libretto (translated by Charles Hart) may be uneven, but Berlioz's score fires on all cylinders throughout, rollicking along at top speed even if the reasons for the excitement are not always clear. Another musical climax with shrieking woodwind and furious brass outbursts? Why not.

Gilliam has not troubled himself about the meaning of life, or the state of early 19th-century French opera, or whether the piece is semi-seria or how it represents the purpose of art. Instead he has put on a great show and allowed the music to breathe. The American-led cast, with Michael Spyres thrilling and golden-voiced in the fearsome title role and Corinne Winters bright-toned with a light, comedic glint as Teresa, had scarcely a weak link. Nicholas Pallesen as the rival Fieramosca, ever lurking and hiding, emerged as a fine performer. Willard White, brandishing gold-plated talons, was ideally cast as Pope Clement VII, riding a Popemobile which would make the real Cellini's outrageous salt cellar for the king of France look plain.

With too little space to celebrate every aspect of this costly extravaganza, one generous donor needs noting: the octogenarian Peter Moores, who has included this production in his Swansong Project. As for Gardner and Gilliam and their forces, no praise is enough. There's a live cinema screening of Benvenuto Cellini on 17 June.

Puccini thought his "California gold rush" opera, La fanciulla del West (1910), among his best. We may agree, yet it remains an acquired taste, teetering on the sentimental but with a blistering, often dissonant score. A new production by Stephen Barlow opened Opera Holland Park's new open-air season with plenty of pizzazz – despite an unpersuasive updating to a 1950s Nevada nuclear testing ground, nimbly designed by Yannis Thavoris.

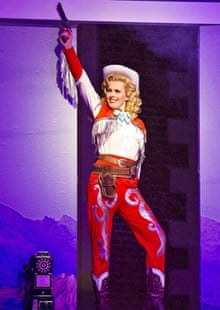

The wide stage created difficulties in Act 1, which was somewhat chaotic. All settled with the big-tuned arrival of Minnie (Susannah Glanville) – camp heroine, mother and would-be lover of all. Here she swings a holster at her hip while standing astride the bar of the Vegas-style Polka saloon. As night closed in and the action grew more taut, so soloists and chorus, crisply conducted by Stuart Stratford, blossomed in confidence. Simon Thorpe (Jack Rance) and Jeff Gwaltney (Dick Johnson) convinced as sheriff and bandit, though neither was quite powerful enough. Glanville alone – warm, potent and alluring, carrying off her Annie Oakley/Katharine Hepburn look wonderfully – had the gleaming tone to scale the orchestral fortissimos.

With the expert City of London Sinfonia, in their raised pit, on constant display, Puccini's score was spread out before us in all its ingenuity. On so many occasions the sonic effects or rhythmic brilliance prompted the thought: "Puccini? Surely not." Webern, an unlikely early admirer of Fanciulla, observed that every bar is "a surprise", the whole never guilty of kitchiness. The stern Austrian miniaturist might have said the same about Benvenuto Cellini. On second thoughts, in ENO's spectacular Gilliamised version, he may have spotted just a hint, a glimmer of kitsch. If this be excess, give me excess of it.

Star ratings (out of 5)

Benvenuto Cellini ****

La fanciulla del West ***

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion