Lord Lechery, Madam Wanton and Judas Iscariot: in a flash these names thrust us into the moral chaos of Vanity Fair, that sleazy pit stop on the grand highway to salvation. Sluts and slatterns, hypocrites and usurers, the naked and the damned tempt the journeying soul to divert from the Celestial City – Christian's destination in John Bunyan's allegory The Pilgrim's Progress – and head straight to Hell.

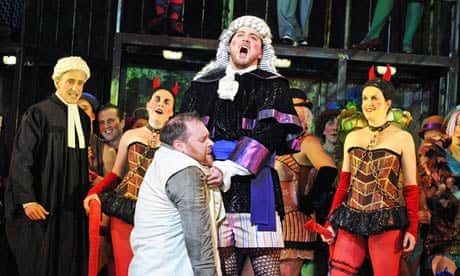

At the Coliseum, in a new staging of Vaughan Williams's operatic version of Pilgrim, they toss in the usual array of dildos and nipple tassels, bare bums and cleavage, to titivate a work high on contemplation, low on dramatic action. They need not have tried so hard. The composer himself makes the most of that scene: the spitting, mewling chorus of sinners provides an interlude of rapid, angular music in a score almost too generous in its unrationed radiance, but compelling nonetheless.

The Pilgrim's Progress was premiered during the Festival of Britain in 1951 and has hardly been seen since. This production at English National Opera, conducted by Martyn Brabbins and directed by Yoshi Oida, is the first fully professional staging for six decades. Since the composer took some 45 years to write it, why hurry?

That said, as an operatic experience – Vaughan Williams called it a "morality" – it is fraught with difficulties. Little happens. The characters are mostly types, not individuals, and all but indistinguishable (Branch Bearer, Cup Bearer, Usher). On this interior journey, you hardly mind whether Pilgrim is in the House Beautiful or the Slough of Despond. Instinctively you recognise the Biblical language – "Teach me thy way O Lord", "Enter in for thou art blessed" and so forth – and know the outcome.

Bunyan's 1678 dream narrative used to be read by all but is now chiefly the province of Eng Lit students or those chugging through the history of English mysticism from Piers Plowman, who falls asleep in the Malvern hills, to the ecstatic poems and "transcendent wonder" of Tennyson. Yet for Vaughan Williams (1872-1958), an agnostic, the book fired his imagination for most of his life. All his musical styles are audible in this rhapsodic score, from the serenity of Greensleeves to the tugging, modal harmonies of the Fifth Symphony, to the solo viola melancholy and ethereal chorus of Flos Campi.

You either respond to this sound world or you don't. I was ready to hear it a second time, immediately. Brabbins, the hero of the evening, conducted a performance of quality and heart, with few weaknesses anywhere in the cast, the outstanding chorus (trained by Martin Fitzpatrick) or the coruscating ENO orchestra.

Though many singers took on several roles, a large ensemble filled the stage. Here are some who shone, rising stars and veterans alike: Benedict Nelson, Aoife O'Sullivan, Eleanor Dennis, Ann Murray, Kitty Whately and Timothy Robinson.

As Pilgrim, ever present and with hardly time to rest his voice, the baritone Roland Wood was dignified and expressive, soaring above the orchestra yet achieving a full spectrum of tonal colour and unforced dynamic contrast.

The production opted for low-key drabness with touches of Noh theatre, as you might expect from the Japanese Oida, a long-time associate of Peter Brook. You couldn't object to the rusty cage-like set, in Tom Schenk's effective designs, or the simple workers' garb worn by Pilgrim and the chorus. There were huge puppets too, another inescapable operatic tic (in the US, you can get a special grant for using puppets in opera. Crazy but true). The whole mise-en-scène, if hardly inspiring, does not interfere. Go for the music.

In 1952, the year Vaughan Williams finally stopped tinkering with Pilgrim's Progress, Oliver Knussen was born. Within a few years this new arrival on the British musical scene had conquered the craft of reading a score – at the Mozartian age of eight! The self-effacing Knussen told a young Joan Bakewell this remarkable fact in 1968, just after his first symphony had been performed by the London Symphony Orchestra, with the composer conducting. He was 15.

A snatch of this interview formed part of Barrie Gavin's TV documentary, Sounds from the Big White House, shown at the Barbican's Total Immersion weekend to celebrate Knussen's 60th birthday. Following the operatic double bill Where the Wild Things Are/Higglety Pigglety Pop! on Saturday, the second day was devoted to orchestral and chamber works. In the Music Hall of Guildhall School of Music and Drama, in addition to violin music delivered exquisitely by Alexandra Wood, two young composers-pianists performed: Ryan Wigglesworth played Knussen's tintinnabulous Secret Psalm (1990, revised 2003) and Huw Watkins the recent, ghostly and atmospheric Ophelia's Last Dance.

In his love of detail, playfulness and precision, Knussen shares the same aesthetic terrain as Mozart and Ravel. Knussen's output is sparse, each piece entering the world with butterfly brilliance but no sense of an outpouring. He has spoken of psychological blocks, but he is also generous beyond belief, and serves music and musicians – as a conductor and an unboastful guru – over and above his own muse.

Does this relative paucity matter? I suspect not. Knussen's Symphony No 3 is one of the most frequently performed, worldwide, of recent Proms premieres, poetically played on Sunday night by the BBC Symphony Orchestra for whom it was written. The Horn Concerto, too, is a contemporary classic. Others may produce more but how many works in their extensive catalogues are given a second hearing? The cream of British composers across the generations turned out to support the much loved "Olly" last weekend, from Edmund Finnis (b 1984), a recipient of a £50,000 Paul Hamlyn award announced last week, to Knussen's senior ally, Alexander Goehr (b 1932).

This shows the breadth of Oliver Knussen's influence. He has championed the new as none other. Two of his own great friends and influences, Hans Werner Henze and Elliott Carter, towering figures in contemporary music, have died in the past fortnight. Knussen won't need reminding that Carter, who was 103, only got into his compositional stride in his 60s. No pressure on Olly, then.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion