Though Scottish Opera brought the fine staging it shared with Opera North and Welsh National Opera to Covent Garden in 1990, it is 40 years since the Royal Opera itself gave a complete staged performance of Berlioz's Les Troyens.

The new production, directed by David McVicar and conducted by Antonio Pappano, is therefore a major event, presenting as much of a challenge to the company's resources as any other single work in the repertory.

It is a long evening in the opera house – five and three-quarter hours on the first night – and the cheers that greeted the final curtain might well have been tinged with relief that the whole thing had finished. There are certainly moments when this production hangs fire. That's partly a result of Pappano's fondness for slow tempi, especially in the second and third acts (he moves the fifth and final one along much more purposefully). But it's also a consequence of the decision to include every bar (or so it seems) of the fourth-act ballet, which, coming so soon after the Royal Hunt and Storm sequence, also choreographed by Andrew George, is too much of a good thing.

The problem is also partly one of Berlioz's pacing, especially as McVicar resists temptations to invent extra business to quicken the dramatic pulse of the tableau-like sections.

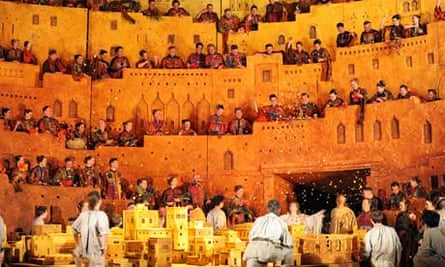

He and designer Es Devlin, with costume designer Moritz Junge, locate the show more or less at the time of its composition, in the 1850s, when Second Empire France was preoccupied with its colonial ambitions. The Trojans in the first part fight in Crimean uniforms, their city protected by walls built from the metal detritus of war; the Greeks' fire-breathing Trojan horse is more huge machine than animal. Dido's Carthage is a colourful, terracotta kingdom, in which a model of the city, like a north African Bekonscot, is the focal point; it's suspended over the stage to suggest the moon of the fourth act, and lies broken in half in the final one, when Aeneas and his retinue leave.

It sometimes seems more glossy pageant than gritty production, and vocal standards are uneven. There's one glorious, totally compelling performance: Anna Caterina Antonacci's Cassandra dominates the first two acts, making every word and every gesture count, always making her presence mean something, and no one else comes close to matching her intensity. As Aeneas, Bryan Hymel, who came into the cast when Jonas Kaufmann dropped out, gained in confidence as the evening went on and made something special out of his final aria, but Eva-Maria Westbroek's small-scale Dido is sometimes touching but never alluring.

Still, Hanna Hipp as Anna and Barbara Senator as Ascanius both make a strong impression, and there are fine contributions from Brindley Sherratt as a gnarled old Narbal and Ashley Holland as Panthus, while Ed Lyon sings Hylas's ravishing aria wonderfully. The components never quite gel, though, into a memorable, epic whole.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion