When I was a child, I would hear stories about how my grandmother hated Charlie Parker. He was the reason, she said, that her son Marcus had died, at the age of 35. Marcus, my mother’s twin brother, was a jazz musician who idolised Parker so much he not only played the alto saxophone, he also copied his heroin use.

Fourteen years Parker’s junior, Marcus also shared a birthday with him: 29 August. The two hung out and played together when Parker came to Cleveland, Ohio. My uncle was only in his late teens then. Like many musicians, he thought Parker’s extraordinary skills were enhanced by his heroin use. But, for my uncle, the music, the drugs and his obsession with Parker ultimately led to prison and an early death. For my grandmother, Parker was the devil incarnate.

So when I heard, through my own musician brother, that a New York-based composer called Daniel Schnyder was looking for a librettist to write the book for an opera about the jazz great, I was intrigued, and set out in search of Charlie Parker, knowing little about him or his music beyond my grandmother’s stories.

I had two and a half years to research, read and listen to everything Parker. It didn’t seem all that long to familiarise myself with his music and his life, then find an interesting dramatic story to support Schnyder’s music – music he could not compose until I finished the libretto.

Schnyder’s only request was to have “his” Parker compose new music for a full orchestra of 40 musicians, something Parker had talked about but never achieved. Such is the beauty of theatre – we can fulfil unrequited wishes.

While I hadn’t tackled a libretto before, I had written several plays, including one about the medical pioneer Dr Charles Drew, whose work is the cornerstone of today’s blood banks. Heavy stuff. One of the few black surgeons in America in his time, Dr Drew was the first African American MD to also hold a Doctor of Science Degree. So, ok I could surely write about Parker. After all, music is less complicated than explaining how to separate blood.

And of course Parker’s name was familiar to me. My grandmother used to say his music was so fast and crazy, it had to be what hell sounded like – frantic, confusing, unrepentant. I understand. It’s exactly how I feel about today’s rap music. But she couldn’t know, and I had to research before I fully understood how important Parker was in the evolution of jazz and music today. Miles Davis once said: “You can tell the history of jazz in four words: Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker.”

By the early 1940’s, Parker, the only child of a Kansas City vaudeville artist and a domestic worker, led a revolutionary movement - bebop - that breathed new life into jazz. A self-taught saxophonist, he learned to play in every key. He stated, “I could hear it sometimes, but I couldn’t play it. I’d been getting bored with the stereotyped changes that were being used. I found that by using the higher intervals of a chord as a melody line and backing them with related changes, I could play the thing I’d been hearing. They teach you there’s a boundary line to music. But, man, there’s no boundary line to art. Once I could play what I heard inside me, that’s when I was born.”

He was able to move away easily from a tune’s “home” key and back without losing the plot. He began stacking swing music’s relatively simple chords with extra notes on top, and then using the additions instead of the core notes as the basis for improvising. Bebop was already waiting to happen, fostered by the frustration of creative younger musicians at the limitations of commercial swing, and the desire of many African-Americans to increase respect for jazz as art-music. But if jazz was poised on a cusp when he arrived, Parker’s genius tipped it into the most liberating transformation since its birth.

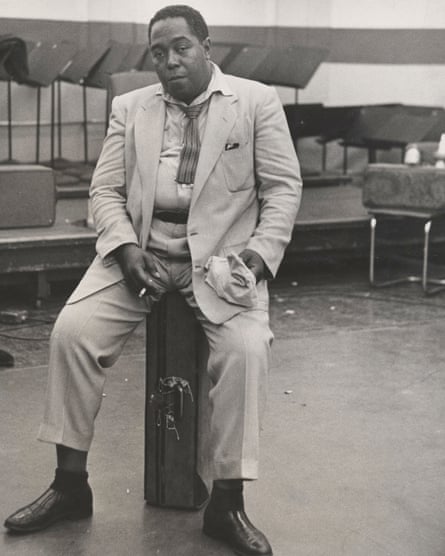

“Music is your own experience,” Parker once said, “your own thoughts, your wisdom. If you don’t live it, it won’t come out of your horn.” He had quite a story to tell, but there was little of it in his own words. In the few recorded interviews that remain, I got to hear a quietly spoken, articulate man. Dizzy Gillespie spoke of his great sense of humour, while his wife Chan said he always treated people with great respect.

This meant I had to uncover – and tell – his story through the lives of the people who knew him best: his mother Addie, Dizzy Gillespie, three of his four wives (Rebecca, Doris, and Chan) and his British-born patroness, Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter (Nica for short) in whose hotel suite he died on 12 March 1955, at the age of 34. “When I met him,” said his second wife, Geraldine, “all he had was a horn and a habit. He gave me his habit.” Indeed, Parker broke the hearts of all the women he loved, including his mother’s. Her words – written for Robert Reisner’s 1962 book Bird: The Legend of Charlie Parker – helped me shape the opera. In her testament, full of raw rage and grief, I got a glimpse of a mother’s undying love and the unrelenting chaos of worry.

While I wanted the opera to be about Parker’s real life, I did not want it to be a typical biography. I searched for those private stories that helped us understand him as son, husband, musician and man. His mother wrote of her terror that he would be lynched, which, given the times, could have been for any reason, but particularly because he dated white women. In the opera, Addie sings about this fear as well as her pride and love for the musician he has become. And when he dies, she sings of the pain in her heart. Through her story, we understand Parker’s.

I usually write to music, so I wrote to his. I read everything, watched every interview and documentary, and got up at 8am every day to listen to Phil Schaap’s Parker-dedicated radio show Birdflight, in which he discusses the significance and nuances of every recording the musician ever made.

I went to the places where Parker worked and played: from Minton’s Playhouse, where bebop was practised nightly, to Jimmy’s Chicken Shack (now Tsion Cafe), where the 19-year-old washed dishes so he could hear Art Tatum play piano. I stood on the corner of 139th street, where Don Walls’ Chili House once stood on Seventh Avenue, the place where Parker expanded his knowledge of harmony and chord substitutions while playing with guitarist Bill “Biddy” Fleet. He also played Harlem’s Apollo Theatre, where last year the opera made its New York debut and outside which his name is now enshrined on the boardwalk.

Daniel Schnyder and I met regularly for those two years at local restaurants and talked, argued, screamed and laughed, and forged an opera out of Parker’s spirit. We wanted to explore this king of improvisation’s creative process, but also his heroin addiction, his unrequited dreams, issues of racism, of segregation, of forgiveness and broken hearts as well as his place in history.

Yardbird begins at the end, with Charlie’s body lying misidentified in the City Morgue, the wrong name and age hanging from his toe. It ends with a stanza from Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem Sympathy, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.

Sometimes I stand on Parker’s name in front of the Apollo and think about his journey and ours. Sometimes when I think of Charlie Parker I imagine him sitting with my uncle Marcus in heaven. My grandmother Lucille is sitting with his mother Addie. They are watching their favourite sons, Charlie and Marcus blow their saxophones loud and free in unison. That makes me smile.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion