Eccentric, brilliant, wilful, unstable, depressive, erratic, witty, morose. Just some of the words that might describe the pianist and composer André Tchaikowsky. But there was also his “dybbuk” – that untrustworthy mercurial Jewish spirit that hovers at your shoulder and will as likely precipitate you into a crisis as magically rescue you from one.

Tchaikowsky was trained early to inhabit an unstable world. At the age of five he was taken with his family into the Warsaw ghetto under his real name: Robert Andrzej Krauthammer. His enterprising grandmother bought false papers to get her and the child out of the ghetto, on which she presciently replaced Krauthammer with the name of her favourite composer: Tchaikovsky. Grandmother and child then spent the next three years on the run in and out of Warsaw. At one stage, André was hidden in the wardrobe of a young, pregnant girl whom he imagined to be the Virgin Mary.

Someone prayed for him anyway, or it was his dybbuk? By a miracle he survived, all the time playing a fantasy piano on any surface he could find.

When he emerged at the end of the war and went back to school, it seemed he had taught himself to play the piano, something that seems typical of the way in which Tchaikowsky acquired knowledge and skill effortlessly (he was later fluent in seven languages). He was soon a protege of Rubinstein and groomed for a career as a concert pianist. But Tchaikowsky’s maverick dybbuk chafed against the social rituals of this role. He was a lethal baiter and hater of “society recital audiences” – and once got his revenge on an insufficiently attentive hall by playing the entire 45 minutes of the Diabelli variations as an encore.

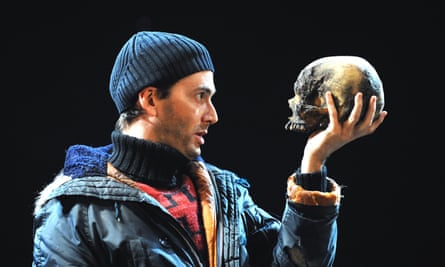

Tchaikowsky was an outsider who cultivated the role, though being a homosexual in Soviet-dominated Poland was about as “outside” as you could get. He defected to England, lived just outside Oxford, and catalogued his tempestuous and active love life as well as his equally tempestuous mood changes in diaries written in superb English – as you might expect from a man whose devotion to Shakespeare led him to leave his skull to the RSC for use in Hamlet, a wish that was fulfilled at the hands of David Tennant and even celebrated on a British postage stamp.

Unfortunately, rather more attention has been paid to his skull than to his compositions. Tchaikowsky had long yearned to be a composer since he studied in Paris, but only gradually forged free time from his money-earning concert duties. He wrote two piano concertos, one of which was premiered by Radu Lupu, two string quartets and some songs, but then turned his attention to his opera The Merchant of Venice, on which he worked from 1968 until his death in 1982.

Tchaikowsky was as much of an outsider as a Jew as he was in any other capacity, but it is riveting that, as a survivor of the Warsaw ghetto, he would choose this play of all possible Shakespearean subjects. But quite apart from his all too authentic experience of antisemitism, it is a brilliant choice for an opera, with a plot that traverses two vividly opposed worlds, each suggesting a different type of musical expression.

Venice is the male world of business, a place dominated by hatred, intolerance and money. Those who seek love, leave. Lorenzo elopes with Shylock’s daughter Jessica, and Bassanio borrows Antonio’s money so he can depart to woo Portia, thereby unwittingly putting Antonio at Shylock’s mercy. By contrast, Belmont, the residence of Portia, is a place of women, love and music. And the strange device of the caskets one of which her wooers must correctly choose to gain her hand, carries an unmistakeable message. The winner, Bassanio, chooses the casket made of lead, not the gold or silver. Money, the primary measure of value in Venice, is worthless here.

Tchaikowsky seized the musical possibilities of these contrasted milieux with astonishing assurance. The two Venice acts are dark and violent. Belmont is scored with exquisite lyricism, coloured with Renaissance references. The music is at times humorous, and brilliantly captures the seesaw developments of Portia and Shylock. As Portia leaves Belmont and triumphs in the man’s world of Venice, so she takes on its characteristics, becoming herself intolerant and malicious, gratuitously grinding Shylock into the dust. In response, Shylock increasingly acquires our sympathy and inhabits a tragic grandeur that was missing from his earlier, grotesque ranting.

Sympathy or not, the issue of antisemitism in the play is not to be ducked, though by casting Shylock and his daughter, Jessica, as black singers in our new production at Welsh National Opera, we suggest the wider context of racism in general. And there is a further irony, in that if there is a self-portrait of Tchaikowsky in the opera, it is not Shylock but Antonio, perhaps the most violently antisemitic figure.

Antonio begins the play with an astonishing speech about depression, a singular way to open a comedy: “In sooth, I know not why I am so sad: It wearies me ...” It later becomes clear that he is in love with Bassanio, a depressive and a homosexual. And at the end of the play, when all the couples have paired off, two characters remain solitary: Shylock and Antonio. Perhaps, in some senses, this is an autobiographical portrait of Tchaikowsky’s heritage and life experience.

The rehabilitation of Tchaikowsky’s opera can definitely be attributed to his dybbuk. At the opening night of Weinberg’s opera The Portrait that I directed at Opera North in 2011, the Russian musicologist Anastasia Belina‐Johnson said to me: “Now that you have resurrected Weinberg, you have to do the same for André Tchaikowsky”

I had not heard that name for 20 years. In my early days at English National Opera I was part of a committee that met to hear Tchaikowsky play a couple of acts of his opera in the hope that we would perform it. Sadly, we said no. A simple decision at the time, but now I can read his diary, and see the bipolar euphoria that preceded his “audition” and the terrible emotional crash that followed rejection. He died a few months later. In between, were a couple of juicy comments typical of Tchaikowsky. He recounts how one “beautiful young man” arrived late – which was me, and then rather gallingly goes on to write: “… followed by an even more beautiful blond who turned out to be Mark Elder”.

The day after my conversation with Anastasia, I flew to Warsaw on a different project, and was standing in the vast marble foyer of the Teatr Wielki when a small figure emerged from the farthest corner of the hall and made his way towards me. As he vigorously shook my hand, he muttered with a broad accent: “Now that you have resurrected Mr Weinberg, you have to do the same for André ...” I needed no further persuading. The dybbuk had spoken.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion