“You cannot live without it - but you have to leave it behind the door of your house, otherwise it will take you completely, it will destroy you, it will eat you”. That’s how the Polish baritone Mariusz Kwiecien describes the experience of preparing and singing the title role in his compatriot Karol Szymanowski’s opera – for many, his masterpiece – Król Roger (King Roger), which opens in its astonishingly belated premiere production at Covent Garden on 1 May. Better late than never.

First staged in 1926 in Warsaw, King Roger is a piece that conjures a soundworld, a drama and musical vision that is rooted in the hyper-expressivities of early 20th century modernism, but it’s also a dangerously intoxicating music drama such that only Szymanowski could have written.

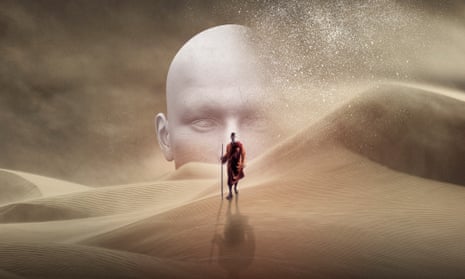

The drama is an outward struggle between ideologies, between conservatism and sensuality, between Christian orthodoxy and pagan abandon – represented, respectively, by the church and the character of the shepherd, who introduces a world of temptation and pantheistic seduction into King Roger’s court. But it’s really about the inner desires and conflicts of the King’s psyche and soul. He is tempted by the Shepherd and the bacchanal he inspires in the opera’s second act, but he is torn by his sense of duty and public persona, although he reaches - perhaps - a kind of acceptance of both sides of his character at the end of the opera. (That’s a moot point; in any case, it’s that inner world that Kasper Holten’s production, which Antonio Pappano will conduct, attempts to find a way to realise on the Covent Garden stage.)

It’s been suggested the character of Roger embodies Szymanowski’s own internal and external struggles. At ease with his homosexuality, he was nonetheless living in a conservative culture in which it simply wasn’t acknowledged let alone accepted. He was a person who dreamt a world of sheer musical dazzle and orchestral sumptuousness that out-emotionates (which isn’t even a word, but seems appropriate for Szymanowski’s music…) and out-exoticizes even Scriabin’s musical imaginarium (as Kwieicen also said: “composing this kind of music you have to be on drugs, or a little bit crazy”), yet he was also a master compositional craftsman, who created these musical and dramatic opiates with absolute precision and consummate care.

At the end of the opera, Roger is suddenly alone, and he sings a hymn to the sun, music of coruscating power. It’s an image that’s open to a multitude of interpretations: has Roger awakened from a dream? Has he decided to reject the Shepherd’s ideology of pleasure? Or has he accepted a new life, a new kind of freedom released by the Shepherd’s “land of eternal ecstasy”? Szymanowski’s music, some of the most definitively powerful of the early 20th century, suggests an expressive certainty in its blinding blaze of colour, but opens a Pandora’s box of dramatic possibilities. But however you interpret it, there is surely a sense of Roger being at last “strong enough for freedom”, as Nietzsche would have put it; someone who stands in “splendid isolation”, as Szymanowski himself wrote in the English title he gave one of his essays written during the composition of the opera.

What’s certain, too, is that the three acts of King Roger contain some of the most ecstatic music ever written for the opera house. And as an operatic proposition, King Roger is an evening of unique concentration and attraction. I think it’s the perfect opera for anyone who hasn’t yet been to the opera house in the flesh: it lasts just 80 minutes, yet it should be a musical and dramatic spectacle of truly hyper-intense, super-operatic emotions, and with Kwiecien, you’ll get to hear arguably the finest exponent of the role anywhere in the world. Take your operatic chance to hear King Roger and follow the conflict that all of us must face between head and heart, between pleasure and rationality, between Dionysus and Apollo.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion