Simon McBurney has a wild glint in his eye as he talks about his new version of The Magic Flute for the English National Opera. "This is not something ossified by 200 years of productions," he says during a break from rehearsals at London's Coliseum, a baseball cap pulled tight around his head. "It's literally physically dangerous."

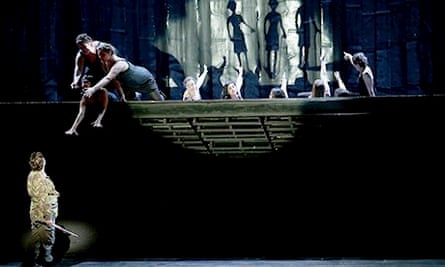

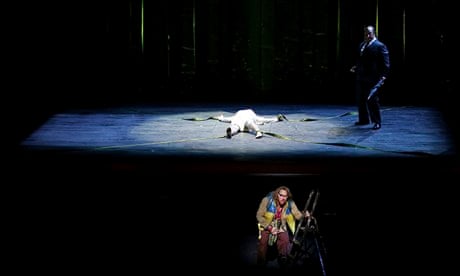

It is, too. During one of Mozart's trickiest quintets, the platform on which the singers are standing shudders and tilts up like the hull of a sinking ship. The Queen of the Night's three attendants, who've been trying to lure Prince Tamino, the hero, and his sidekick Papageno back to the dark side, slide towards oblivion – singing as they go. And then there's the Queen of the Night herself. With its breakneck coloratura and high Fs, her showpiece aria – The Vengeance of Hell Boils in My Heart – is hard enough to sing while standing still. But here, she's rolling around in a wheelchair, wielding a knife and being pawed by her errant daughter, as does the impressive Cornelia Götz.

So why is the Queen of the Night in a wheelchair? "There are lots of paradoxes in Mozart," says McBurney. "She says she's losing her power. But then she goes on to sing one of the most demanding arias in opera. So if we're to treat what she says seriously, the question becomes how do we physically show her growing powerlessness?I thought the wheelchair would do that. By the end of the opera, she can hardly move."

McBurney, the award-winning 56-year-old founder of Complicite theatre company, who's appeared in The Vicar of Dibley and Rev, and had screen roles in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and Harry Potter, came late to opera, and even later to Mozart. "For years, I wasn't in the least bit interested in opera," he tells me over a post-rehearsal drink. "The productions were so wooden, the plots so fucking obscure, everything so fucking pointless. And I never got Mozart. I thought he was light, frothy, insubstantial."

With all due respect, I say, that's nuts. "I know. I'm very slow and stupid, so I only gradually understand what's going on." He removes his baseball cap, and orders more crisps and a second glass of Talisker whisky. "Mozart's seeming frothiness is just a light touch with very profound material. That's what I've found working on The Magic Flute." You didn't know this before you started work on it? "No. It's always like that for me: a journey where you don't know where you're heading." That must be interesting for your actors and singers. "Interesting, yes. It's pretty much always a diabolical pact for them. As it is for me."

What audiences will see later this week in McBurney's Magic Flute is the ancien regime dying before them and the European Enlightenment struggling to be born. The wobbling, tilting, swinging, hovering platform is a visual metaphor for humanity in crisis. After the Queen of the Night's attendants tumble off, the platform rights itself like a mechanised flying carpet, and Tamino and Papageno head off to endure further ordeals before they can get their girls and achieve enlightenment.

"The Magic Flute, I think, is fundamentally asking what is it to change people's consciousness," says McBurney. "What makes it evolve? This was an important question when this was first performed two years after the French revolution - and now. When we performed this in Amsterdam we got a big laugh when Sarastro says we're in a crisis. We were in 1791 and we are now."

On stage, Papageno is wondering aloud why he can't just get the girl without having to go through all this fuss: trials by fire and water, plus lewd propositions from scantily clad regal lickspittles. The opera's answer seems to be that you aren't in the Garden of Eden any more, sunshine, you're in a modern world where you don't pull fruit from the trees or immediately receive the object of your sexual desire, but have to suffer, struggle and use your wits and rationality to get what you want. Even then there's no guarantee of success.

Yet the struggle is is our predicament, what makes us human rather than animal. This is the vision that fires McBurney. "The opera is politically, philosophically and musically profound," he says. "And sexual. I just got a text from Stephen Fry saying, 'Good luck with your flute. Oo-er.' Zauberflöte is German slang for penis. The opera's original audiences in 1791, when Die Zauberflöte premiered in Vienna, would have immediately grasped a lot of the resonances we struggle to understand. They'd have recognised the Queen of the Night's coloratura singing as old-fashioned, and her rival Sarastro's singing as something more modern. In a sense, she's the dying ancien regime, and he's the new dawn. They'd have got that political subtext from the music."

Traditionally, says McBurney, the second half of The Magic Flute was so dull you might nod off. It is unlikely to happen here. The pacing is snappy, the production dense with multimedia effects. A sound-effects artist in a glass chamber stage right makes a rustling noise echoed centre-stage as Papageno fumbles with a sweet wrapper. A video artist stage left projects images and directs the singers with arrows that appear behind them on a screen. And when the singers speak, they are mic-ed up so they can move more freely around the stage yet still be heard. When they sing, though, the mics are turned off. The sound design alone makes it one of the most technically virtuosic operas ever put on in London.

"It's the most demanding production we've ever staged," says ENO artistic director John Berry. This co-production with De Nederlandse Opera (their engineers built the amazing hydraulic system) was performed in Amsterdam to rave reviews last year and now Berry is hoping for similar success. Berry is the man responsible for attempting to revive ENO by luring in celebrated directors (Terry Gilliam, Rufus Norris, Mike Figgis and of course McBurney) to work in opera for the first time. He's also the man who smiles when I mention the boos that Calixto Bieito's Fidelio got at ENO recently: "Part of the territory."

It was Pierre Audi – former artistic director of London's Almeida and since 1988 artistic director of De Nederlandse Opera – who first persuaded McBurney to face down his operatic prejudice, proposing that he direct an adaptation of Mikhail Bulgakov's absurdist novel Heart of a Dog in a DNO-ENO co-production in 2010. "I love Russian literature," says McBurney, "and I adore Bulgakov. I've long been fascinated by that pre-war Soviet era." Indeed, that fascination has yielded some of his and Complicite's best work, notably 1994's adaptation of Daniil Kharms's Out of a House Walked a Man (with an original score composed by his Russophile musicologist brother Gerard) and 2011's adaptation of The Master and Margarita.

"Once Pierre had got me sucked into opera, he kept mentioning The Magic Flute, saying I'd get a kick out of directing it. I thought, 'Bollocks.' Other opera directors warned me off, saying they couldn't see how to make it work."

So how is he making his production work? "My proposition is that music is at the heart of what The Magic Flute means, that it's Mozart's music, not the words, we should be attending to. Music expresses what can't be expressed otherwise. It reminds me of the music of the Chukchi people of north-eastern Siberia."

Really? He gives me a sidelong glance. "Oh yes. Really." McBurney recommends I listen to his choices for Radio 4's Desert Island Discs last year. Not I'm the Slime by Frank Zappa (though that is superb) or the fifth movement of Schnittke's Concerto Grosso (ditto), but throat singer Veronica Oucholin's rendition of I Light the Fire. At the time he told presenter Kirsty Young: "I understood through my father [the late American archaeologist Charles McBurney] that in neolithic times, humans felt they were part of the world of animals and echoes of that time the vestiges, can still be heard today, which is why I've chosen this piece from the Chukchi people."

What's that got to do with Mozart? "It's very simple. Mozart is saying: that which cannot be articulated otherwise can be expressed in music. The magic flute changes people and so do the bells. It's the great prophetic opera. All this is taken on by Beethoven, Wagner, Hitler, Stalin, maybe even the Beatles."

So now McBurney is in love with the art form he disdained. He and Argentine composer Osvaldo Golijov are currently trying to create a libretto for an opera about which he will tell me nothing. "I'm also planning to do operas with Damon Albarn and the Pet Shop Boys, and maybe something involving Beethoven."

But first Mozart. It would be absurd to judge a production on a single rehearsal, but one impressive and symbolic thing McBurney has done is to raise the orchestra from the pit to a level where the audience can actually see it. For once you'll be able to study the first clarinettist's dandruff from the cheap seats. It was Wagner at Bayreuth who first shoved his musicians into the Nibelheim-like bowels of the Earth.

"For Wagner," says McBurney, "that was about mysticism. I want to do the opposite – to take the audience from darkness to light, to make us evolve, to end mystification and embrace reason and rationality. That, as I understand it, is what the opera is about."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion