A book about a movie is a familiar thing. Most readers are likely to have seen the movie and are thus able to judge the book against the original. A book about a theatrical production, by contrast, is rare because unless a production is videoed, it disappears forever into the memory when the show's run is over. It is a fair bet, therefore, that any theatrical production that does generate a book is a memorable one.

I possess only two volumes of this kind. Both fulfil with ease that condition of memorability. The first is about Peter Brook's 1970 RSC production of A Midsummer Night's Dream, a triumphant staging whose imaginative allure still captivates those of us who saw it more than 40 years ago. The second was published two years ago in German by Antonia Goldhammer. Its subject is Stefan Herheim's astonishing 2008 production of Wagner's Parsifal at the Bayreuth festival. Each was a theatrical milestone.

Herheim's Parsifal, which brought the work, the composer, the Bayreuth festival and the history of modern Germany together in a series of stunning stage images, catapulted him to international fame. "The Parsifal did not change the way I work, but it certainly made me more spotlit than before," he tells me when we meet in London. That is some understatement. Today, Herheim is one of the most in-demand opera directors, especially for his Wagner. His production of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg was the star turn of August's Salzburg festival, and was immediately bought up by the New York Metropolitan Opera.

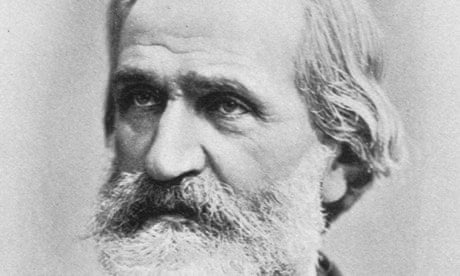

Herheim has worked across Europe since his first production, Mozart's Magic Flute, in 1999. But the Berlin-based Norwegian has never, until now, worked on opera in Britain. This month, as the centrepiece of the Royal Opera's celebrations of the Verdi bicentenary, Herheim is tackling the Italian composer's most neglected mature work for the stage. Verdi's Les Vêpres Siciliennes, written to a French libretto for the Paris Opera in 1855, is a sprawling five-act story of love, conflict and politics set against the background of a rising against the occupying French in 13th-century Sicily. It has never held a secure place in the repertoire – indeed, it has never been performed at Covent Garden before.

"The working conditions here are excellent," Herheim says. "People are so kind and enthusiastic." But any continental director arriving to work in London these days has to battle against the reflexive scepticism and even hostility that British audiences and some critics reserve for any much-touted foreigner. Calixto Bieito's recent staging of Fidelio for the English National Opera is only the latest of many such shows that may have poisoned the well for strong-minded and interventionist directors of whom Herheim is definitely one. There is no denying the October premiere will be a high-profile and high-wire affair.

Part of this is down to Herheim's working methods. He always works with a team. The Vêpres, like the Bayreuth Parsifal and other Herheim productions, is a collaboration with his convivial and erudite dramaturg Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach and costume designer Gesine Völlm. "I am the captain of the team, definitely," he says. "But I'm a very communicative captain and I need the teamwork on the level where we can discuss everything. But I am very perfectionist. This can be a blessing and a curse."

Is there a trademark Herheim way of doing an opera? "It's not about talking about the piece," he says. "It's about feeling it and trying to make the instrument in my hands – the operatic machinery – express it. My approach starts with the music, much more than with the text. The text is absolutely secondary in my work. For me the score is the text and when the music says something different from the text, I follow the score. Music speaks a language beyond words, beyond anything speakable, and this is what fascinates me."

Meier-Dörzenbach agrees. "Our approach to opera is very interdisciplinary. We look at what is happening in painting or in politics at the time a piece is written. But Stefan started as a musician. He is a trained cellist. He reads the score. A lot of directors are unable to read a score. He allows the score to open the door to new rooms. The important thing is that no image on the stage conflicts with the music."

Of the four Herheim productions that I have seen – all of Wagner – none embodies the truth of his and his team's comments better than the Tannhäuser he produced in Oslo three years ago, in which the Bacchanale in the sensual realm of Venus erupts into a manic allusive celebration of the operatic form. In a brilliant kaleidoscope, famous scenes from all kinds of opera take place on the stage simultaneously: Madam Butterfly prepares for suicide; Octavian presents the silver rose to Sophie; Boris Godunov broods; Mimi coughs; Lucia sends herself mad while, at the moment Wagner's score calls for castanets, a toreador and the cast of Carmen parade across stage. At the height of the mayhem, Tannhäuser sings his first line: "Too much, too much. I should not have woken." At which point the stage empties.

Described on the page, all this may sound a bit nerdy and indulgent. True, there's an element of that; Herheim has sometimes been criticised for his micromanaging and for the incredible visual detail of his shows. But at the same time, there is such ebullience here, such wit and joy, too, that even the most staid operagoer is likely to cheer when Herheim and his team get it right, as they often do. In the Salzburg Meistersinger, for instance, there is a brilliant Alice in Wonderland coup in which Hans Sachs's room suddenly becomes just the desk on which the cobbler-poet is working, so that all the characters are turned into giant Biedermeier versions of themselves, creating a fairytale world for a staging that draws heavily on the aesthetic of the Brothers Grimm.

"My productions are detailed because I am fascinated by the little details of the score as well as the big things," Herheim says. "It matters to me why the composer has used this D major here and that D minor there. The rhythms and the rhythmic changes matter. There is no tone that does not have a thought behind and within it. I also think opera can convey more than one thought at a time, including some ambiguous ideas. I love challenging myself, the team and the audience."

How does a director who has scaled the Wagnerian heights to such acclaim deal with the change of gears that Verdi requires? "For me, Verdi is in general the hardest composer to stage," Herheim reflects. "He's tricky. It seems on one level so straightforward, even sometimes banal: the form is so clear; the music is so simple; it tells you immediately what it is supposed to be about. The difference between Wagner and Verdi is like night and day. Yet Verdi has a concision and a pragmatism. He often called himself un uomo di teatro – a man of the theatre – rather than a composer."

Les Vêpres adds two further and specific challenges, however. First, most of the audience have never seen the piece or know or care greatly about the history of 13th-century Sicily. "It's certainly not a drawback to be knowledgeable about the piece," says Herheim. "But the important thing is to feel that it makes sense."

Second, the work is problematic, in its mix of French and Italian operatic traditions. "I am very aware that most people will be afraid that it's going to be a long and perhaps slightly boring evening because they know it is maybe not the best piece by Verdi. My job is to find a key to the door that opens the room in which the drama can take place so the music becomes dramatically compelling. I'm not sure yet if it really is going to work. I wish I could tell you in a very strong and brilliantly intellectual way how it will turn out. But I know what I am hunting for."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion