John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress obsessed Ralph Vaughan Williams throughout his long life. He turned to the 1678 religious allegory again and again, writing music for it first in 1906; 45 years later his opera, Pilgrim's Progress, was premiered at Covent Garden, London. The composer was never a Christian (he moved from "atheism into cheerful agnosticism" according to his second wife, Ursula), but he felt sufficiently inspired by Bunyan's text that he kept a copy of the book with him while he served in the first world war's trenches.

Bunyan's book, famously written when he was in prison for preaching outside the auspices of the Church of England, tells of an everyman figure – Christian – who journeys from his home, the City of Destruction, to the Celestial City on Mount Zion. You might not know the work, but you'll have heard of its Vanity Fair, the Slough of Despond, or Doubting Castle, and you will probably have sung the hymn, He Who Would Valiant Be, whose words are from part two of the book, and whose music (in the form it's sung today) was composed by Vaughan Williams in 1906. That same year saw his first musical treatment of the text when he composed incidental music for a local amateur stage presentation of selected scenes. Some 15 years later he wrote a popular one-act opera based on the episode The Shepherds of the Delectable Mountains (a section of which was eventually incorporated into his 1951 opera), and, in 1925, he started work on the full-scale opera, writing its first two acts over the next decade. On deciding it was unlikely to reach the stage, however, he abandoned the project, recycling some of its themes in his Fifth Symphony.

But Pilgrim's Progress hadn't finished with him, and the BBC would reignite Vaughan Williams's interest when they asked him to write incidental music for a radio dramatisation of the work (broadcast in September 1943) in which John Gielgud played the Pilgrim. Vaughan Williams returned to the opera, brought the whole thing together, and it had its world premiere at Covent Garden in 1951, as part of the Festival of Britain.

Yet, this was almost the end of the story. The opera's reception was, at best, lukewarm. Critics didn't like it, and it seems those involved in the production didn't have much faith in it either. It was a huge disappointment for the composer; it had been a work he had felt compelled to write. He made some changes, extending the Vanity Fair scene with help of the poet Ursula Wood (later his wife), inserting the wonderfully louche aria for Lord Lechery. Apparently, a Cambridge University production in 1954 vindicated Vaughan Williams's belief in his work. So why has it not been performed in Britain on a professional stage for more than 60 years?

I've lived with the score for several weeks, and I believe I am in the company of a masterpiece. In Pilgrim's Progress we get the very best of Vaughan Williams – both the gentle lyricism of his pastoral style, and his darker side that lived with the horrors of war. There's an incredible luminosity to the orchestral writing, and the principal characters are blessed with wonderful vocal lines that are precisely shaped to reflect both their personality and the dramatic situation. The exciting and vivacious Vanity Fair scene is a masterpiece, adding a moment of musical and dramatic light relief. (Certainly, in ENO's new production, this scene will be a feast for ear and eye.) The work's crowning glory comes just two minutes before the end, when we get a fantastic wall of sound from an on-stage and off-stage chorus, off-stage brass and, of course, the orchestra giving it their all in a final, climactic Alleluia!. There's a slow inner momentum to much of the music that, if you're not careful, can drag a little. Perhaps this is one of the things that did for it at its premiere. Conducting, I've got to be careful to keep the pacing of the piece in accord with the drama on stage.

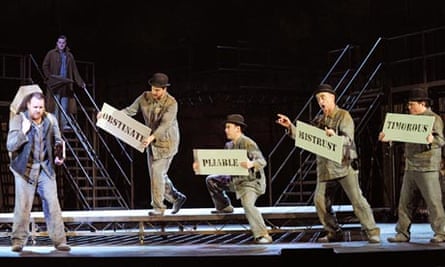

Admittedly, it's an unconventional opera – Vaughan Williams preferred to refer to it as a "morality" – and it needs a careful and thoughtful approach. Our production has that, thanks to Japanese director Yoshi Oïda and Dutch designer Tom Schenk. Both – by their own admission – knew little of the man or his music beforehand. Yoshi has changed the name of the central character from Christian to Pilgrim, taking his cue from Vaughan Williams, who once explained: "I wanted the idea to be universal and to apply to anybody who aims at the spiritual life, whether he is Christian, Jew, Buddhist, Shintoist or Fifth Day Adventist." Yoshi, himself not from a Christian tradition, took this as a green light to venture beyond a specifically Christian journey: our production features an everyman figure on a universal journey towards spiritual enlightenment. Tom Schenk's set, meanwhile, is a giant jigsaw puzzle that can be rearranged into any number of different configurations, playing an important unifying role in the production: the same pieces are a castle, or a highway, or a prison cell, depending on how they're fitted together. It's fantastically effective, especially when you see it moved into place. The gallant set-moving brigade have been rehearsing almost as hard as the singers!

As music evolves in today's postmodern world, and audiences become familiar with such a bewilderingly wide array of musical languages and genres, perhaps now, 60 years after its premiere, The Pilgrim's Progress will not simply be judged in relation to the vogues of a particular era, but will be allowed to speak on its own terms. I hope we can establish its latent reputation as a 20th-century masterpiece.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion