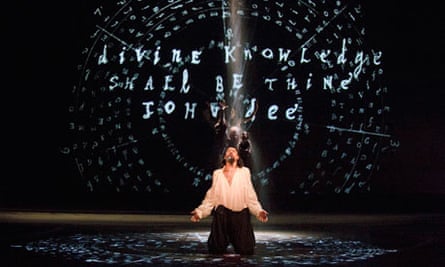

Elizabethan England is enjoying a revival in the public imagination, with Shakespeare integral to the 2012 Cultural Olympiad and Damon Albarn's opera Dr Dee, about Elizabeth I's maverick astronomer, opening on Monday night at the Coliseum in London.

It's worth remembering that Renaissance England was a diseased landscape. Average life expectancy was 35 years, more than 80% of patients at St Bartholomew's Hospital had syphilis and Elizabethans were terrified of the bubonic plague. Superstition was rife and witch-hunts were common. But this period was possibly Britain's most intellectually fertile and we can trace the origins of modern scientific enquiry to the reign of Elizabeth I.

Dr John Dee (1527-1609) was effectively the queen's science adviser. An astronomer, mathematician, navigator, alchemist, spy and celestial necromancer, Dee was a larger-than-life magus figure. He was probably the inspiration for Christopher Marlowe's character Doctor Faustus, Ben Jonson's The Alchemist and Shakespeare's Prospero.

Dee also advised Elizabeth's spymaster Francis Walsingham on national security and the establishment of a network of spies, and his code-breaking efforts helped expose Catholic plots to dethrone the queen. He signed himself 007, inspiring the codename of Ian Fleming's alter ego. Dee taught Raleigh and Drake "the perfect art of navigation" for calculating longitude from lunar distance observation, which helped facilitate the establishment of the British Empire.

Infamous in his lifetime, Dee was a risk-taker and exceptional scholar. With his eye on the court he rejected the comfort of university tenure at Cambridge, preferring to collate and categorise his data independently. A serious bibliophile, his private library became the largest in Britain. Dee charted the movement of the planets and in his early career toured Europe giving talks on astronomy – a form of science outreach that was entirely new.

He was opposed to a tiered system of education where those without classical scholarship were held back, so when his translation of Euclid's mathematics was complete he made the arcane information accessible to non-university-taught artisans and craftsmen. In his General and Rare Memorials Pertaining to the Perfect Arte of Navigation, he advocated the usefulness of mathematics as a "Publick Commodity".

Dee was a mystic who attempted to talk to angels, but he also believed that numbers formed the basis of all phenomena and designed geometric algorithms to fathom the solar system. His students included Francis Bacon, promoter of the "scientific method", and the astronomer Thomas Diggs, who believed the universe to be infinite.

It is to the enigmatic Dr John Dee that we must look for the origins of Britain's contribution to modern Western science, yet Dee has been largely left out of the history books – why?

The bedrock of modern Western science is its empirical methodology, in which phenomena are measured and experiments repeated. But in Dee's time it was predominantly God and celestial beings who gave man answers.

The life of a Renaissance scientist could be hazardous. Being a star gazer and conducting experiments frequently necessitated secrecy; alchemy could be confused with witchery – a crime punishable by death. In 1600, astronomer Giordano Bruno was burnt at the stake for daring to say the sun was a star.

Within Dee's lifetime Copernicus's sun-centric theories would be strengthened by Galileo's discoveries. In direct contradiction of Christian and classical teaching, astronomy was proving man and Earth were not at the centre of the universe after all. Dee's life and personal beliefs straddled this time. He skillfully mixed fact and fiction not only to juggle astronomy and astrology, but also to ensnare the enemies of the state.

Dee was collaborative in nature and a spiritual man; he appears to have been drawn to debate and the stimulation of the shared experience. It was this open thinking that made him a true Renaissance man, but it was this same openness to ideas and exploration that was his undoing. As astronomy opened up the heavens, Dee wanted to transcend the knowledge available to him and find divine answers to this new infinity – answers that at this time, just prior to Galileo's Starry Messenger, only omnipotent celestial beings could give.

Occultist Edward Kelley befriended Dee in the 1580s and they collaborated on alchemical and magical investigations. Kelley distracted Dee from his other areas of interest and persuaded him to move to Poland and tour the country giving lectures on magic and alchemy for the aristocracy and at universities. Polish Catholics became aware of their necromancy and they had to defend their position to the church to save their lives.

It was during this time that Kelley told Dee the angels wanted them to swap wives. Dee reluctantly agreed and nine months later his wife had a son, whom he raised as his own.

Gossip and scandal dogged Dee. He apparently regretted this period of his life and he parted company with Kelley. On his return to England he found his library destroyed and robbed of its contents. After Elizabeth's death Dee fell out of favour with James I's court and he died penniless at what was then the great age of 82.

In the last days of rehearsal at the Coliseum I met up with the opera's director Rufus Norris and Marek Kukula, Public Astronomer at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich (see the video at the top of this page). Norris explained that in some regards Albarn identifies with Dee's drive for understanding. The opera also attempts to unravel what it means to be English and how we might combine imagination and spirituality in our lives alongside the reductionism of science.

Dee's claim to know the language of angels and his magical use of a scrying ball and obsidian mirror have been largely responsible for historians playing down his contribution to the origins of Western science, preferring to cite his students Bacon and Diggs. Albarn wants to put the record straight and in his opera, in which he also performs, he explores both Dee's painful vulnerability and the astronomer's prescience.

I was actually at the Coliseum to interview Albarn, but with first-night production concerns he had no spare time for interviews. So I went up into the gods with Kukula and Norris to talk about the production and Dr Dee's legacy, while Albarn fretted and strutted on the stage below as live ravens flapped around the auditorium.

Last-minute panics nothwithstanding, this opera is going to be spectacular.