Opera Australia 2024 Review: Idomeneo

By Gordon Williams(Photo: Keith Saunders

In her thought-provoking program essay on “Idomeneo,” the final opera in Opera Australia’s 2024 summer season which premiered at Sydney Opera House on Feb 20, director Lindy Hume quotes Anne Carson’s “Grief Lessons” of 2008: “Myths are stories about people who become too big for their lives temporarily, so that they crash into other lives or brush against gods.”

Somehow this wonderfully conveys the power of Mozart’s “Idomeneo.” But, how much backstory is necessary to get a sense of this ‘crashing’? And how precarious is the mythic dimension if the backstory that prefigures the characters is not as clear to a 21st century audience as it might’ve been to an 18th century one? Idomeneo was among the Greek assassins lurking in the belly of the wooden horse that their enemies, the Trojans, were tricked into bringing into their city. Do many members of a contemporary audience come to the theater knowing this? Maybe it is not vital that they should.

There was something deep yet indefinable, or perhaps deep because indefinable, in Hume’s production. That was the overall impression, even if we didn’t exactly know in advance how ruthlessly the title character could hang onto power.

The sense of directorial absorption in study of this story was palpable, a sense of watching something magnificent and consequential. We learned early on that Idomeneo has made a bargain with Neptune if his own life is saved on the sea voyage home from war and that that bargain is to sacrifice the first person who happens along, who turns out to be his own son. There are great stakes thrusting our attention on Idomeneo, and in the title role, Canadian tenor, Michael Schade certainly warranted our attention.

Schade’s portrayal of Idomeneo contained plenty of that “untethered, homeless quality” Hume pointed to in her program essay. His torment was palpable in the great number “Fuor del mar” where Idomeneo equates the raging of his emotions to the tossing of the seas. The great weight of authority on Idomeneo’s shoulders was palpable in his supplication to Neptune, “Accogli, oh re del mar.” But we were also in the throes of watching an almost superhuman traversal of emotion, able to share with Idomeneo the sense of relief when he assuages the god by abdicating power. “Oh me felice” Schade sang at the end (“I am content”, according to the surtitles) with a flautando quality in his voice that was just exceptionally moving for those of us who had traveled with Idomeneo on his punishing journey.

And there was also a sense of hearing something magnificent, in the rich activity of the Opera Australia Orchestra under the direction of German conductor, Johannes Fritzsch, Conductor-Laureate of the Queensland Symphony Orchestra.

This orchestra told in so many ways – in the continual excitement of the accompaniment (witness the eloquent bassoons pointedly underlining Idomeneo’s acceptance that Neptune will not cease his threats), the tricky-sounding shift, back and forth between secco and instrumental recitatives (a challenge for conductors since Christian Cannabich conducted the very first performance in 1781) or even passages that sounded like metrical modulations, such as that leading into Elettra’s “Tutte nel cor vi sento” in which this daughter of Agamemnon gives vent to her fear that the Trojan princess-currently-prisoner, Ilia, may become Queen of Crete through Idamante’s love for her.

It felt like a flawless cast. Emma Pearson’s emotional gamut as Elettra, jealous of Idamante’s love for Ilia, ranged all the way up to a keening fury. Australian mezzo-soprano Caitlin Hulcup was completely convincing in the ‘trouser role’ of Idamante, Idomeneo’s son, beloved of Elettra, but in love with Ilia. Soprano Celeste Lazarenko made sense of her every word and emotion as Ilia. Portraying the daughter of the Trojan king Priam, she enlisted our sympathy as she quietly reflected on her situation with the question: “Shall I love a Greek?”

In smaller roles, Scottish tenor John Longmuir as Arbace managed to make an informative continuity of transfers from secco to stromentato recitative while Melbourne-born tenor Kanen Breen conveyed alarming urgency as the High Priest concerned with the state of the rattled Idomeneo’s kingdom, a contrast to Breen’s previous, somewhat comic roles – “Magic Flute” Monostatos or Rameau’s Platée.

“Listen for the chorus” we were advised before the performance and the Opera Australia Chorus sounded terrific, especially those warm, hushed male voices supporting Idomeneo’s plea to Neptune to abate his anger or the final full chorus, “Scenda Amor,” but a most striking effect was created by chorus movement, a courtly dance in Act two where a mere rising up of the whole ensemble on toes as part of a sequence of movements was extraordinarily and even inexplicably moving. Also worth noting was the blocking of the ‘suffering’ quartet as the shifting of the four principals’ vocal lines saw visual representation in the singers’ stepping on and off a revolving stage in varying combinations.

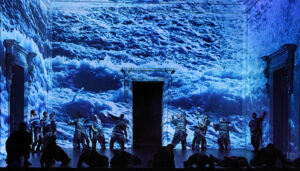

Hume’s production made intelligent use of back-projected video, by David Bergman, Catherine Pettman and Rummin Productions, of Tasmania, the island state that could be thought to stand in a similar southerly relationship to Australia as Idomeneo’s Crete to Greece. Tasmania’s sea cliffs stood in for Crete’s and Ilia sang her “Zeffiretti lusinghieri” as if in a southwestern fern forest. There could almost have been more made of this unique, mythic landscape, but enough had already been achieved by this production to convince a modern audience that the 25 year-old Mozart’s “Idomeneo” was profound enough to stand with the masterly operas he composed later in the 1780s.