Lyric Opera’s “Champion” packs a powerful emotional punch

It’s rare that a curtain call provides one of the high points of an opera evening. But when Reginald Smith Jr., portraying the elderly, dementia-ridden Emile Griffith and Justin Austin as Young Emile the boxer, entered from opposite ends of the Lyric Opera stage to meet in the center and embrace to cheers and a rousing ovation it seemed the perfect way to end a successful performance.

One was not expecting to be overwhelmed by Terence Blanchard’s Champion, which opened at Lyric Saturday evening in its Chicago premiere. The jazz trumpeter-composer’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones, presented by the company in 2022, proved disappointing, undone by a pallid score, unwieldy narrative and overlong duration. If his second opera fell that short of the mark, what would his first opera be like?

On the contrary. Champion proved a much stronger work across the board—musically, dramatically and visually, in this dynamic and often spectacular staging, a co-production between Lyric and the Metropolitan Opera, where this show opened last season.

Champion is inspired by the true-life story of boxer Emile Griffith who won world titles in three different weight divisions. The opera begins in the elderly Griffith’s small apartment where the retired boxer is in confusion due to his ring-related dementia. From there the fast-paced narrative flashes back and forth from his childhood as an abandoned orphan in St. Thomas, youth as a baseball player and hatmaker, his emigration to New York, locating his mother, and his fast boxing rise, aided by manager-trainer Howie Albert. Act I builds to the championship grudge rematch with Cuban fighter Benny “Kid” Paret to regain the welterweight title. At the weigh-in, Paret taunts Griffith by calling him maricón (a derogatory Spanish slur equivalent to “faggot”). In the 12th round, Griffith unleashed a relentless assault with 17 punches to Paret’s head before the fight was stopped. Paret lapsed into a coma and died ten days later. The controversial fight (available online) and Paret’s death haunted Griffith for the rest of his life.

The other, less interesting focus in the opera is on the bisexual Griffith’s gay side—which he was ashamed of and conflicted about in his young days—understandably so, considering the times and the macho world of boxing. That side of his life is painted with episodic, somewhat campy scenes in a gay bar headed by sassy proprietor Kathy Hagen.

Though he continued to box for another 15 years, Griffith was never as successful after the Paret fight, likely because he was afraid of seriously injuring another opponent. Eventually Griffith retires at the urging of Howie. Divorced and lonely he returns to the gay bar outside of which he is severely beaten by a gang of (presumably homophobic) thugs. (The actual 1992 attack landed Griffith in the hospital for four months.) Frail and diminished by dementia and the beating, the elderly Emile with the aid of his young partner/adopted son Luis befriends the son of his former adversary, Benny Paret Jr., and is finally able to forgive himself.

While the music for Fire in My Bones centered on a kind of mid-tempo jazz noodling that felt bland and aimless, Blanchard’s score for Champion is much richer and more varied and textured. There are driving, percussion riffs building up tension for key scenes, and solo arias for all the major roles that reveal character in distinct emotional peaks, as well as duets, trios and ensembles. In short, as an opera, Champion is much closer to the real thing.

Apart from the opera’s finale having more endings than Symphonia domestica, the one weak point is the libretto (as was the case with Fire as well). Here playwright-actor Michael Cristofer’s plain-spun, often coarse verbiage strains to find a poetry and eloquence to match Blanchard’s music in the emotional high points but invariably falls short.

So, while Champion may not be a timeless masterpiece, it is an intensely moving and humanistic work. The extraordinary cast sang and acted with total conviction, making Saturday’s performance a hugely compelling night in the theater.

First among the principals was Reginald Smith Jr. as the older Emile. From the opening scene where the elderly boxer is looking for his shoes and sings a plaintive little aria (“My shoe goes where it goes. And I go where?”) Smith wholly embodied the man’s dementia-related confusion. Singing with a cavernous baritone, Smith is often a witness to scenes from Emile’s past life, sometimes duetting with his younger self. Dramatically, Smith took on the essence of the ailing Emile with his diminished, old-man shuffle and hesitant confusion in one of the most heartbreaking performances one will ever see in an opera house.

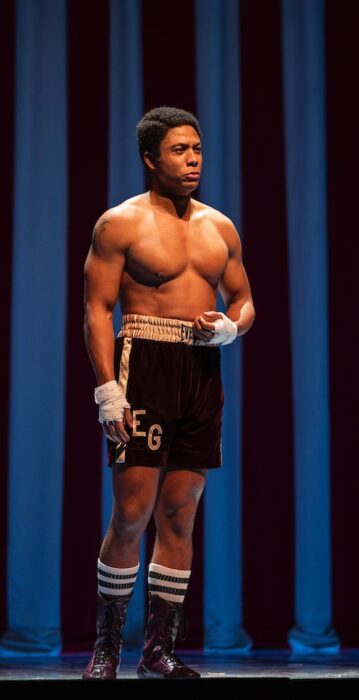

Justin Austin contributed a star-making turn as young Emile. The baritone was a charismatic figure, wholly credible in the ring with his boxer physique, as well as conveying the conflicted Emile’s tentative exploration of New York’s gay milieu. Austin maintained a credible island accent and sang superbly throughout. His prefight aria, “What Makes a Man a Man?” is the pivot-point of the entire show, and Austin delivered the aria with searching rumination, building the emotional intensity to a soaring climax.

The libretto’s treatment of Emelda, Emile’s slatternly but loving mother flirts with sit-com caricature at times (as with the seven children she has lost track of). Still, Whitney Morrison delivered a scene-stealing performance, making the most of her two big arias with powerful top notes.

(The close synergy among the three principals was notable, all of whom also appeared in Fire Shut Up in My Bones. Smith played the supporting role of Uncle Paul, and Austin and Morrison took on the lead roles of Charles and Billie for the latter half of the 2022 Lyric run after a Covid wave hit the opening-night cast.)

Paul Groves was a characterful presence as Howie Albert, Emile’s milliner employer turned cigar-chomping boxing manager and father figure. Repeating his role from the Met, Groves delivered a fully lived-in performance as the gruff but supportive Albert (seemingly a composite of Howie Albert and Griffith trainer and later boxing commentator Gil Clancy).

A late sub for the indisposed Leroy Davis, Sankara Harouna was most impressive in the dual roles of Benny Paret and his son, Benny Jr. The baritone powerfully put across the trash-talking boxer as well as doing an effective 180 as his more subdued and empathetic offspring. (Harouna, a Chicago native, will become a Ryan Center member next fall.)

As Luis, Martin Luther Clark unveiled an impressive rich tenor in the opera’s latter scenes. Clark’s understated portrayal nicely etched a portrait of Emile’s fitfully frustrated but sympathetic partner who helps the old man with his tasks of daily living.

The young Naya Rosalie James sang the role of the little boy Emile with fine clarity and impressive intonation and high notes in “This night is long.”

The large cast was filled out with several strong performances in smaller roles: Meredith Arwady as the sassy Texas Guinan-like proprietor of the gay bar; Larry Yando as a leather-lunged ring announcer/narrator who also make ironic comments on the action; Krysty Swann as the sadistic Cousin Blanche who abusively punishes little Emile by making him hold cinderblocks over his head; Ian Rucker as two generations of bar patrons; and Meroe Khalia Adeeb as Emile’s affectionate but understandably perplexed wife.

Champion has the same production team as Fire Shut Up in My Bones, though, like everything else, the staging for this show is flashier and much more effective.

Allen Moyer’s sets efficiently swung in and out to paint a number of locations from Emile’s apartment to rustic St. Thomas, Albert’s hat shop, a gay bar, Madison Square Garden’s boxing ring and Central Park. The towering visuals and projections were often stunning, with a flying plane, New York street scenes, massive blowup photos of the real Griffith and vintage posters of fight playbills (projections by Greg Emetaz).

Director James Robinson moved the well-rehearsed action at a crackling pace, aided by the atmospheric projections and Moyer’s fast set changes. The intermittent dance sequences kept the proceedings lively as with the Caribbean Mardi Gras and later 70s-style ensemble, even if the latter sometimes recalled the Solid Gold dancers.

Enrique Mazzola can be frustratingly uneven in standard repertory but proved a superb advocate for Blanchard’s score opening night. The company’s music director led an energetic performance with driving momentum that kept the action moving at a fast clip. Blanchard’s jazz-tinged style and scoring always came through and the standout solo moments made effective dramatic and theatrical impact.

Champion continues through February 11. lyricopera.org

Posted in Performances