It’s amazing what a bit of holiday reading can achieve. Unwinding in the sun, James Clutton, the enterprising artistic director of Opera Holland Park (OHP), reached for one of Simon Mayo’s adventure yarns and was immediately struck by its operatic potential. Last week, that poolside inspiration burst into sparkling, vivid life with the world premiere of Itch, an exciting, moving, relevant new opera – and an undoubted hit.

Composer Jonathan Dove and librettist Alasdair Middleton have devised a compelling piece of music theatre, telling a fast-paced story with power, grace and wit that will surely go into the repertory. Clear direction from Stephen Barlow and stylish design by Frankie Bradshaw add hugely to the whole experience.

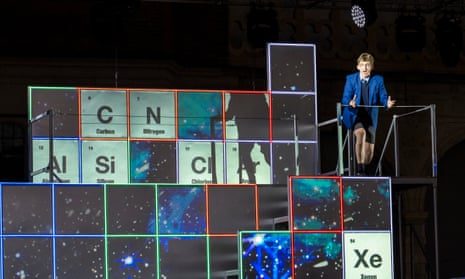

Itch is Itchingham Lofte, an endearingly nerdy schoolboy desperate to collect all the elements in the periodic table. His obsession translates to the ingenious set: the periodic table itself, made up of illuminated boxes that spell out the element symbols while doubling as a screen for some impressive video images. Itch’s quest leads to the discovery of a rock containing a previously unknown element, a source of energy that could end the climate crisis or – in the wrong hands – be a danger to the entire planet. In a week when people voted against Ulez while swathes of Europe went up in flames, this piece could hardly be more timely.

Dove’s pulsing, shimmering score imbues Middleton’s strong, direct libretto with a hectic urgency, pushing the narrative along, with only rare moments of traditional operatic introspection. It’s an exhilarating ride, one made all the more intense by the startling range of colour Dove extracts from just 12 members of the City of London Sinfonia; wind, brass with percussion and a single violin, cello and bass, all tightly controlled by conductor Jessica Cottis.

Clean-toned tenor Adam Temple-Smith makes an impressive OHP debut as the irrepressible Itch, one half of a splendid daring duo with his kleptomaniac sister, Jack (bright soprano Natasha Agarwal). Seasoned American baritone Eric Greene also makes a welcome debut at Holland Park, giving a tender portrayal of their father, Nicholas.

Dove’s hugely successful opera Flight (1998) features a coloratura soprano as a domineering air traffic controller and a mystical countertenor who wanders lost in an airport. Characters who mirror those originals turn up in Itch: spectacular Rebecca Bottone is the permanently angry boss of a dodgy energy company, Greencorps, and lyrical James Laing is an eco-conscious beach bum. There’s excellent support from soprano Victoria Simmonds as teacher Miss Watkins and baritone Nicholas Garrett as a scheming Flowerdew, the villain of the piece.

The never-ending slate-grey skies of her Port Talbot childhood form the backdrop for Adele Thomas’s debut production at Glyndebourne. To her, those skies represented a hemming in of her ambition, a paradoxical limitless horizon that gave no opportunity to move out into it. She translates that feeling of claustrophobia to ancient Thebes in Handel’s Semele, where the eponymous heroine feels trapped by her father’s demands that she make a loveless marriage. Semele has other ideas. She doesn’t want to just leave Thebes, she wants to live with the gods, and she sees Jove, king of them all, as her passport to immortality – an ambition that is to be her fiery undoing.

Disappointingly, those grey skies rarely clear. They permeate Annemarie Woods’s stage design and Hannah Clark’s costumes. Chilly blacks and greys inform the mood of the whole piece, which feels strangely subdued and withdrawn, even when Jove is in his pastoral paradise – though his fetching citrus suit does relieve the gloom.

Part of the problem is the work itself. It was conceived as an English oratorio, which is a different animal from Handel’s other great oeuvre, Italian opera. Yes, it features spectacularly operatic showpiece arias in the Italianate da capo style, but the greater emphasis on chorus numbers, however beautifully sung, slows the narrative and weighs down the drama. Thomas attempts to alleviate this by giving the chorus stylised movements and gestures, but on a raised platform strewn with debris that inhibits their ability to move about freely.

A fine cast of principals bring a refreshing range of vocal vibrancy to this drab scene, aided by the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, under Václav Luks, making his Glyndebourne debut. American soprano Joélle Harvey in the title role is a bright, vivacious star, while her Jove, tenor Stuart Jackson, rarely thunders. Instead, he is all tender sensitivity (Where’er Ye Walk is almost a whisper). Mezzo Stephanie Wake-Edwards is an implacable Ino, sister to Semele, and Jennifer Johnston makes a scarily imperious Juno, who wakes Somnus (splendid Clive Bayley) to wreak her revenge on Semele. Yet Thomas’s cult-like Thebans turn Semele’s immolation into a disturbing, distasteful spectacle, as far from an ecstatic death as can be imagined.

The annual Proms visit by Sir Mark Elder and the Hallé is always an event, but this year’s Russian programme was exceptional. Can there be a current British orchestra with a better string sound? The sheer finesse they brought to Shostakovich’s fifth symphony was ravishing, particularly in their wondrous handling of the pianissimo passages in the first movement and the central largo. The romping bombast of the finale was terrifying, but again it was the glistening pianissimos within that movement that really impressed.

We began with Rachmaninov’s curiously dark choral symphony The Bells, based on the florid poetry of Edgar Allan Poe, which honours the bells that mark the joys and sorrows of life. Even with 220 singers, the combined Hallé and BBC Symphony choruses struggled at times to be heard above the huge orchestra, but the glorious voices of soprano Mané Galoyan, tenor Dmytro Popov and baritone Andrei Kymach rang through the texture with appropriate bell-like insistence.

Star ratings (out of five)

Itch ★★★★★

Semele ★★★

Prom 16 ★★★★

Itch is at Opera Holland Park, London, until 4 August

Semele is at Glyndebourne, East Sussex, until 26 August

All Proms are available on BBC Sounds. The Proms continue until 9 September.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion