When opera lovers think of the Ring, it’s in conjunction with four epic 19th-century operas composed by Richard Wagner known collectively as the Ring Cycle. Now the renowned Metropolitan Opera Company, founded in 1883 in New York, has added a boxing ring to the dialogue.

On Monday night, 10 April, the Met unveiled its first production of Champion - an opera based on the life of former world welterweight champion Emile Griffith. There will be nine performances running through 13 May. The 29 April performance will be broadcast live in high definition in 47 countries around the world including the United States. In the United Kingdom, the telecast will be available in 155 cinemas located in 19 cities.

Griffith’s career as a professional boxer began in 1958. Less than three years later, at age 23, he was welterweight champion of the world. Unlike today’s world where multiple sanctioning bodies dispense championship belts like trinkets at a carnival game, it was an era when boxing had only eight world champions.

During his 19-year sojourn through boxing, Griffith engaged in 111 fights and boxed the staggering total of 1,122 rounds, 337 of them in championship competition. That’s 51 more championship rounds than Sugar Ray Robinson fought. His final record was 85 wins, 24 losses, and 2 draws. Many of those losses came long after he should have retired. He’s on the short list of the greatest welterweights of all time.

Griffith was gay.

Let’s put that last sentence in context. In the early 1960s, gay sex was illegal in 49 out of America’s fifty states. As noted in Donald McRae’s brilliant biography, A Man’s World: The Double Life of Emile Griffith, “The onslaught against homosexuality ran deep and wide. The state and the church and the courts, the police and the doctors, the newspapers and the magazines, the rich and the powerful, the poor and the illiterate, were united in their condemnation of men like Emile Griffith. A homosexual, to them, was sick and cowardly. He was depraved and absurd.”

On 17 December 1963, a 5,000-word investigative report headlined ‘Growth of Homosexuality in City Provokes Wide Concern’ was featured on page one of the New York Times. The article warned, “Sexual inverts have colonized three areas of New York. The city’s homosexual community acts as a kind of lodestar, attracting others from all over the country. The old idea, assiduously propagated by the homosexuals, that homosexuality is an inborn incurable disease has been exploded by modern psychiatry. In the opinion of many experts, it can be both prevented and cured.”

“Amid such oppression,” McRae wrote, “the idea of Emile coming out in public as a gay man would not just have invited disbelief. It would have been a criminal act which could have resulted in his imprisonment. The mystery of Emile Griffith was buried tight inside him.”

On 24 March 1962, Grffith fought Benny Paret at Madison Square Garden. At the weigh-in prior to the bout, Paret openly derided Griffith as a “maricon” (a particularly demeaning anti-gay slur). That night in the ring, Griffith beat Paret to death. For the first time ever, a man was killed on live national television.

Griffith was haunted by Paret’s death. He fought for 15 more years but was never the same fighter again.

Worse times lay ahead. At age 54, Emile was savagely beaten by a gang of thugs as he left a gay bar near the Port Authority Bus Terminal in New York. His skull was fractured and he was hospitalized for four months. Later, severe dementia pugilistica (now known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy) set in. There was a long sad decline until his death in 2013 at age 75.

The music for Champion was composed by Terence Blanchard, who crafted the score for several Spike Lee movies and is also an accomplished jazz trumpeter. Michael Cristofer, who won a Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award for The Shadow Box, wrote the libretto.

Champion was first produced in 2013 at the Loretto-Hilton Center for the Performing Arts in Missouri. There was a second production in San Francisco and a third at the John F Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington DC. Blanchard wrote an opera after Champion - Fire Shut Up in My Bones - that was produced by the Met in 2021. That marked the first time the Met had performed an opera by a Black composer.

For some aficionados, an opera hasn’t been performed until it has been performed at the Met. Anthony Davis, the composer of X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X (which will be produced by the Met during the 2023-24 season) speaks to that point, saying, “One of the things that makes having your work performed at the Met so special is the resources you have at your command. The singers, the orchestra, the staging and production, costumes, lighting, everything. It’s an affirmation and a culmination.”

Two artists, both bass-baritones, sing the role of Emile Griffith in Champion. Ryan Speedo Green is the young Emile. Eric Owens plays Emile’s older self, haunted by the ghosts of his past.

Green, age 37, had a troubled childhood that included two months in a juvenile detention facility when he was 12 years old. He’s now an emerging star in the world of opera. “Someone with my background wasn’t supposed to be in the position I’m in today,” he says. Friends and colleagues call him Speedo, which is his real middle name.

Is that nomenclature a tribute to the 1950s doo-wop song sung by the Cadillacs?

“I wish it was as cool as that,” Green answers. “My father was a body-builder and I was born on April Fool’s Day, so he named me after underwear.”

Green stands 6ft 4in tall and, not long ago, weighed 345lbs. Recognizing the danger, he’d begun the process of losing weight and was down to 310lbs when he was offered the role of the young Emile.

“I made a promise to myself and to Terence Blanchard when I accepted the role that I would take full advantage of it,” Speedo says. “That meant I would sing the part and I would look the part to the best of my ability.”

Green is now a well-muscled 245lbs, feels healthier than he has in years, and says that the weight loss hasn’t adversely affected his voice. This is his first leading role at the Met.

“I always wanted to be on the operatic stage performing with colleagues,” he recounts. “I was happy to play any role I was given. Now I’m discovering that I can be the person who carries a show, and that’s very exciting to me. Every role I’ve had up until this point in my life has prepared me for this moment.”

Owens, age 52, has been widely praised for his artistry and says, “I think it’s wonderful that the Met is putting on a contemporary story like this. I hope it draws a new audience to opera and opens people’s minds as to what opera can be.”

As rehearsals progressed, Owens took note of the fact that arias and chorus parts were being revised from the original score and observed, “The atmosphere in the rehearsal room has been special. One reason for that is we have the composer here at our service, which you don’t have with Strauss or Verdi.”

Neither Green or Owens has been to a professional fight. They have only a passing familiarity with boxing and the sport’s big names.

“I didn’t know who Emile was before I heard about the opera,” Owens acknowledges. “Now I look at old interviews with Emile and see a good man who’s searching for forgiveness. But first he has to forgive himself.”

And what would Emile think of Champion?

“I think he’d be fascinated by it all,” Owens answers. “How many people have an opera written about them?”

Former WBO heavyweight champion Michael Bentt was hired by Champion as a boxing advisor. Little mistakes are magnified under bright stage lights, just as they are in a boxing ring. That meant the fatal fight scene involving Griffith and Paret and other boxing moments had to be choreographed and rehearsed until they were performed perfectly every time.

“All boxers deal with identity,” Bentt says. “We all put on a mask of one kind or another. But the mask that Emile had to wear; I can’t begin to imagine what it was like to carry that burden.”

One might draw a parallel between opening night at the Metropolitan Opera and the glitz and glamour that accompany a major championship fight. I was at the Met for the opening night of Champion.

The Met is one of the world’s great opera houses, a place where the music of the ages is elegantly presented and brilliantly performed. Twenty-one hanging crystal chandeliers overlook a sea of burgundy and gold. A huge stage with seven hydraulic elevators offers endless possibilities for production.

Opera isn’t meant to be historically precise. And Champion isn’t. But it captures the pain, shame, pride, joy and passion of Emile Griffith’s journey in powerful fashion.

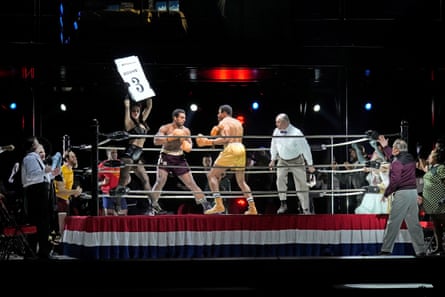

The original production in St Louis had 18 people in the cast. This production has eighty. When Champion was performed in St Louis, four dancers walked onto the stage and held up ropes to create the illusion of a boxing ring. At the Met, not only is there a boxing ring, it spins around to signify the passage of time.

When the performance on opening night came to an end and the applause was cascading down, I found myself reminiscing about Emile. He was one of the first people I met when I started writing about boxing four decades ago. Over the years, a ritual greeting developed between us. Whenever we saw each other at a fight, at an awards dinner, wherever, Emile would say, “Hi, Tom.” That was the trigger. I’d respond by pointing in his direction and blurting out “Sugar Ray Robinson!” Then he’d laugh and give me a hug. We did it dozens of times.

Toward the end of Emile’s life, a young man named Luis Rodrigo served as his caretaker and companion in a very loving way. One night, I saw Emile and Luis at the fights and went over to say hello. There was a hint of recognition in Emile’s eyes but nothing more. No “hi, Tom.” So without prompting, I pointed and said, “Sugar Ray Robinson!”

A look of panic crossed Emile’s face. “No! No! No!,” he cried out. “Emile Griffith!”

As the curtain calls for Champion ran their course, I thought back to that moment and imagined how Emile would feel if he were healthy again and in the audience for the presentation of his life story by the Metropolitan Opera. Most likely, he would have been overwhelmed with emotion and filled with wonder that he was the foundation for such a glorious spectacle. One by one, he’d give everyone involved with the production a hug followed by a heartfelt “thank you.”

If I’d been sitting with Emile at the opera, I would have told him that he should be proud he was a great fighter. But more important; that he was a source of hope and inspiration for a marginalized people and that the culture has changed to become more accepting of who he was and the life he led.

But first, I’d point and say, “Sugar Ray Robinson!”

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. Among his writing credits, he is the author of The Final Recollections of Charles Dickens, published by Counterpoint. In 2019, Hauser was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.