United States Giddens & Abels, Omar: Guest Artists, Chorus and Orchestra of LA Opera / Kazem Abdullah (conductor). Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles, 30.10.2022. (JRo)

United States Giddens & Abels, Omar: Guest Artists, Chorus and Orchestra of LA Opera / Kazem Abdullah (conductor). Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles, 30.10.2022. (JRo)

Production:

Libretto – Rhiannon Giddens

Director – Kaneza Schaal

Production – Christopher Myers

Sets – Amy Rubin

Costumes – April M. Hickman & Micheline Russell-Brown

Lighting – Pablo Santiago

Projections – Joshua Higgason

Chorus director – Jeremy Frank

Choreographer – Kiara Benn

Cast:

Omar – Jamez McCorkle

Omar’s Mother – Amanda Lynn Bottoms

Johnson/Owen – Daniel Okulitch

Julie – Jacqueline Echols

Auctioneer/Taylor – Barry Banks

Owen’s Daughter – Deepa Johnny

Katie Ellen – Briana Hunter

Abdul, Omar’s Brother – Norman Garrett

Abe – Alan Williams

Amadou – Ashley Faatoalia

Olufemi – Cedric Berry

Suleiman – Patrick Blackwell

Principal Dancer – Jermaine McGhee

Rhiannon Giddens has turned the personal narrative of Omar Ibn Said, a West African Islamic scholar, into a universal story for all faiths. Omar is an enthralling opera with a clear message of man’s inhumanity to man. But the physical beauty of the production and the tenderness and power of the score, magnificently handled by the Los Angeles Opera Orchestra under Kazem Abdullah, move the message beyond despair to offer hope and transformation.

The opera is a collaboration between Giddens, who trained as an opera singer and is a noted roots musician, and Michael Abels, a composer of film scores and concert works. Giddens’s talents are too numerous to mention and, in this libretto, she has created a poetic evocation of suffering and the uplifting of life through faith. After recording herself singing the score, she sent it to Abels who took her material and orchestrated it into a dynamic and sweeping opera. Senegalese music, traditional Arabic rhythms, spirituals, bluegrass, jazz, ragtime, hoedown, hymns and hints of Gershwin and Copland all combine in Abels’s hands to coalesce into an orchestral work with unique style, sumptuous textures and lyrical vocal lines.

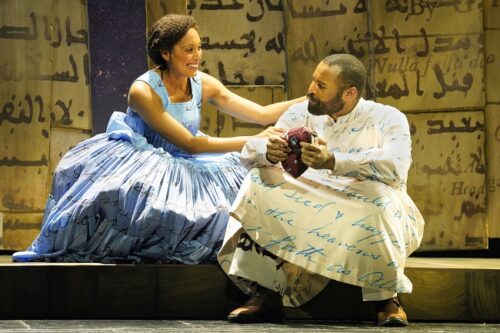

The libretto, based on Said’s memoir, follows him from his home in what is now Senegal to the slave ship that carried him and other prisoners to Charleston, South Carolina. There he is sold to a brutal plantation owner. Though Omar has yet to learn English, he understands the words of a young slave, Julie, who urges him to escape when he can and make his way to Fayetteville and the plantation of a kindly slaveholder. In Fayetteville, Julie and Omar are reunited and share a particular bond. Julie has saved Omar’s cap which had been tossed off in the auction. It seems she remembers her father wearing a similar cap and praying on his knees while facing the rising sun. Omar, through the spiritual guidance of his dead mother, Fatima, and the kindness of Julie, learns to accept his life and transform it through the written word, hoping that his life story will bring courage and faith to others.

The characterizations of slaveholders and slaves walk a fine line between realism and caricature and succeed in bringing portraits of individuals to complex life. Owens, the kindly slaveholder, is nevertheless a man convinced of his superiority. His daughter, Eliza, is still innocent enough to want to make a home for Omar, whose writing in his jail cell impresses her. The commands of the monstrous slaveholder, Johnson, as he chastises Omar, are translated into surtitles of pidgin English, showing just who is the primitive and who is the civilized man. The auctioneer sings in shades of Gilbert and Sullivan, underscoring his malevolence with absurdity. Julie’s fellow slave, Katie Ellen, has a sunny disposition underlaid with the gravity of what’s at stake.

Under Kaneza Schaal’s intelligent direction, a soulful dignity imbues the performances. In one eloquent moment, Owens and Omar pray and sing ‘Hallelujah’. Owens drops to his knees, and Omar remains standing: that simple action speaks volumes about the dignity of Omar despite his feigned acquiescence to Christianity.

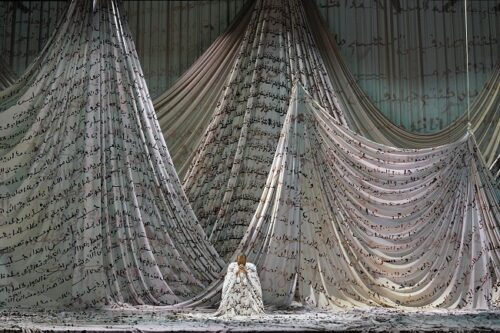

The sets and costumes, in no small part, contribute to the poetry and mood of Omar. In fact, it is unimaginable that the opera could ever be produced without them. They are brilliantly realized by set designer Amy Rubin and costume designers April M. Hickman and Micheline Russell-Brown. Rubin’s imaginative use of fabric, Arabic letters, archetypal slave imagery, rope and scrims is breathtaking. To name a few memorable effects, there is cream-colored drapery imprinted with Arabic writing that flares out in tented shapes across the stage, a massive skirt in the same print that enthrones Omar’s mother on high and a huge tree of rope. The video projections of Joshua Higgason are eloquent, and the lighting design of Pablo Santiago creates a harmonious whole.

Jamez McCorkle is a superb Omar – his tenor fluid and gracious. The orchestration and conducting leave enough air around the text to allow the beauty of McCorkle’s instrument to shine. The dramatic soprano of Jacqueline Echols as Julie soars when she sings, ‘What else do we have but memories in darkness’, a shining aria of grief and remembrance. As Fatima, Omar’s mother, Amanda Lynn Bottoms’s voice has rich color and tone. All three vividly inhabit their roles.

In the dual roles of Owens and Johnson, Daniel Okulitch is a standout, as was Deepa Johnny as his daughter. All the soloists are exemplary: bass-baritone Alan Williams as Abe, tenor Barry Banks in another dual role, baritone Norman Garrett as Omar’s brother, mezzo Briana Hunter as Katie Ellen and Ashley Faatoalia, Cedric Berry and Patrick Blackwell in the poignant roles of captured slaves on the ship. The chorus, whether in the world of African homeland, auction block or plantation, is excellent

For me, there is only one flaw in the opera. Unfortunately, it is the conclusion and that tends to color the overall impression. Instead of trusting the audience to understand the message of Omar, Giddens and Abels present a didactic ending. Omar preaches to the audience as the chorus intones his message. It feels more like a religious service than an opera finale. The composers may have wanted a splashy ending, but a quieter one would have sufficed.

The brilliance of the opera is that it works on many levels: spiritually, politically, socially and religiously. Its universality is what makes it a work of art. The merging of world music done so elegantly in the score reinforces this – no further preaching necessary.

Jane Rosenberg

Masterful, moving and profound? The story of Omar certainly is all of these, but I don’t think Giddens manages to make this into a compelling opera. The story is brutal, the opera tame. It lacked drama. Omar has profound faith, but his character was stoic to the point of blandness. It struck me as one-dimensional and then it became preachy. Abels’s interestingly eclectic score and excellent voices, scenery and costumes didn’t save the day. I left the opera house wanting to be impressed but was disappointed. I wanted to be generous but … I wonder if, with our sensitivity to the BLM era, critics are tippy-toeing around the problems with this opera.

I haven’t seen the opera but have been following with interest. I wonder if we might find that some now popular operas were poorly received at opening. Sometimes, it takes several iterations to get things more right. Think about what tweaks might make it more dramatic for you. After all, we are talking about an educated man, enslaved for something like 47 years who had to survive and shape a life under that yoke. To me, that would certainly tamp down a lot of drama.