A thunderous hammering of feet on the floor greeted the curtain calls of Parsifal, semi-staged by Opera North at its home venue, the Grand theatre, Leeds, before touring throughout this month. This noisy physicality added to the collective excitement unique to a great live performance. The epic length – five hours with two intervals – of Wagner’s last music drama, and the grandeur of its redemptive ending, almost guarantees a warm response, even if its quasi-religious scenario remains obdurately opaque. The outstanding forces of Opera North, conducted by its former music director Richard Farnes, made Tuesday’s performance one to remember.

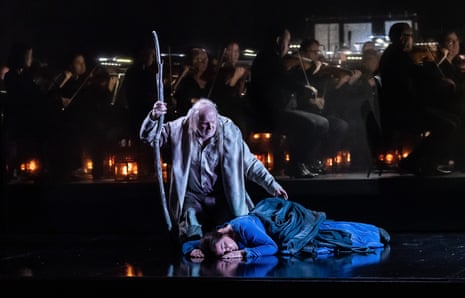

The company’s Wagner journey began in 2016 with successful concert stagings of the Ring. Its first Parsifal has orchestra and conductor on stage, the action taking place in front and behind in Sam Brown’s simple but striking staging, ingeniously lit by Bengt Gomér. A board of lights variously glimmers and dazzles to suggest the strength and decay of the grail brotherhood at Monsalvat. (Other venues will be concert stagings only.) The baby at the end is tacky, and the knights, with their hoods up, have the look of hobbits, but everything else works well. Special praise to Robert Hayward’s fine Amfortas, the stricken leader who sings nobly and has to endure the indignity, half-naked, of his sanguivorous knights feasting on his wound. They may have been acting but it looked hideous.

If the central theme of this 1882 opera is compassion, its chief advocate is Gurnemanz, whose two huge narrations, in the first and third acts, work as buttresses to the entire opera. In the Lancashire-born, world-class bass Brindley Sherratt, making his debut as the veteran knight, Opera North has a star. His gift for lyrical Italianate repertoire, for which until recently he was better known, brings radiance to a role that can sound booming. His delivery had clarity and variety, every note secure. Bass voices take time to ripen: his is at its best.

All round this was a magnificent cast. As Parsifal, also making his role debut, Toby Spence has supreme vocal confidence but also negotiates intelligently the demands of being both catalyst and foil, destroyer and redeemer. Katarina Karnéus, as Kundry, is strong in this complex figure’s different guises, with terrifying and brilliant top notes in her Act 2 outpouring. Derek Welton made an immediate impact as the magician Klingsor. The rest of the cast – including Titurel (Stephen Richardson), the Esquires and Flowermaidens, as well as the enlarged chorus – gave sterling performances. Farnes’s pacing keeps the music moving, but allows the essential space and amplitude needed. David Greed, leader of Opera North’s superb orchestra for its entire 44 years, will step down at the end of this tour. His successor will have a job to keep the string sound as luminous and precise as it was here.

Tchaikovsky’s views on Wagner swerved from admiration (of the music) to rebuttal (of the associated cult and the mumbo-jumbo that went with it). The Russian composer’s own perfect opera, Eugene Onegin (1879), based on Pushkin and blessedly free from metaphor, is as direct a summation of human experience as you could hope to find. Opera Holland Park opened its 2022 season with Julia Burbach’s production, conducted by Lada Valešová and designed by takis. At the second performance last weekend, not everything gelled vocally but many key moments proved arresting, capturing the work’s intensity and passion, especially at the shattering midpoint, when the drama spins out of control.

Burbach makes us think hard about the opera’s interior world, perhaps at times confusingly for those unfamiliar with the story, but always perceptively. Each character – the susceptible Tatyana (Anush Hovhannisyan); her vivacious sister Olga (Emma Stannard); the brutish but beguiling Onegin (Samuel Dale Johnson); the tragically ardent Lensky (Thomas Atkins) – is sympathetically handled. The period staging looks handsome, with elegant, adaptable sets in shades of ivory. Onegin and Lensky are compelling and well matched. Supporting roles are expertly taken, especially the Larina of Amanda Roocroft, herself once a glorious Tatyana, and Kathleen Wilkinson’s Filippyevna. The revamped OHP stage, in the round with the City of London Sinfonia in the middle, is a far more enjoyable experience for the audience but still presents problems of ensemble. You can be sure that OHP, a company with a “naught availeth” ethos, will work fast to solve this.

The visionary notions of Alexander Scriabin make Wagner’s looks lucid in comparison. They cannot be compressed into a short paragraph. Let’s stick with his synaesthesia, which in his case meant perceiving sound as colour. For his tone poem Prometheus: Poem of Fire (1910), for piano and orchestra, he dreamed up a light scheme, using a specially invented “keyboard for lights” to heighten the experience. Bold Tendencies, living up to it name, opened its ambitious 2022 season, which takes place in a south London multi-storey car park, with a sold-out Scriabin double bill.

Performed by the Philharmonia, complete with “live” lighting faithful to the score’s instructions, the Poem of Fire was in every aural and visual sense a blast. If you want cosmic, it was cosmic. Samson Tsoy triumphed as the intrepid piano soloist. Gergely Madaras was the impressive, authoritative conductor, keeping a grip on this seething multicoloured ocean of orchestral sound. In comparison, the Poem of Ecstasy (1908), dominated by an irrepressible solo trumpet, is more straightforward and merely orgiastic. It was written in a tiny rented room on the Italian Riviera, noisy with street sounds and trains roaring past the window. It might have been designed for this now renowned car park. The season runs until September. Try it.

Star ratings (out of five)

Parsifal ★★★★★

Eugene Onegin ★★★★

Scriabin: Poems of Ecstasy and Fire ★★★★★

Parsifal tours until 26 June

Bold Tendencies’ live programme continues until 10 September

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion