The Karrawirra Parri/Torrens River runs through the heart of Adelaide and, for the opening week of the Adelaide festival, it’s lit up like Christmas — even the nearby Adelaide Oval is bathed in the rainbow colours of pride.

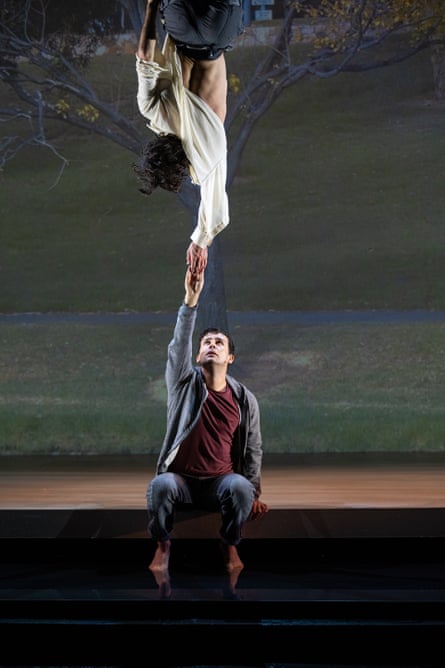

Inside the Dunstan Playhouse, Watershed is also built around the water. Behind a simple white stage a tranquil scene is projected, the footage filmed at a spot just a few hundred metres up the river. A lone figure (Mason Kelly) descends from the rafters in slow motion; suspended from a cable with an unbuttoned shirt draped dramatically over his frame, he’s posed like an idol in a renaissance artwork — Saint Sebastian, perhaps, or Christ in Michelangelo’s Pietà.

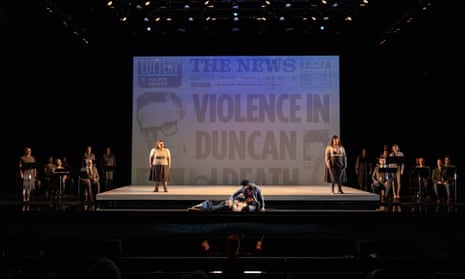

As he floats over the stage, the 18-strong Adelaide Chamber Singers narrate a moment from 50 years ago. “The night’s offerings are of sweat and spit and cum,” they sing with church-like reverence.

It’s the scene of a beat, a place where men would meet after sundown without speaking words or exchanging names. As the dancer twirls in the air, the lyrics reveal the beat’s secret rhythms and rituals, its tenderness and grit, in a way that turns this rite of the shamed and marginalised into a kind of sacrament.

But the man isn’t flying – he’s drowning. On the night of May 10 1972, Dr George Ian Ogilvie Duncan, a law lecturer at the University of Adelaide, was thrown into the river. The circumstances of his killing, the suspected involvement of police officers and its impact on nation-leading gay rights reform in South Australia are the subject of this newly commissioned work, premiering just shy of the 50th anniversary of Duncan’s death.

Watershed is presented as an oratorio; it’s not a fully-staged opera, but the songs are delivered with simple, powerful flourishes by the director, Neil Armfield, and choreographer, Lewis Major – a restraint that suits the sobriety of the occasion.

The librettists, Alana Valentine and Christos Tsiolkas, grapple with how to tell his story in song. They resist the temptation to neatly, retroactively cast Duncan as a martyred hero; he was a quiet, private man who may never have identified himself as homosexual nor envisioned himself as a rallying figure for gay rights.

There’s also a reckoning with the privilege and status that allowed this professor’s death to needle the conscience of mainstream Adelaide in a way that the uncounted, anonymous victims of earlier gay bashings had not. On this note, Ainsley Melham appears as the “Lost Boy”, a nameless narrator in hoodie, jeans and T-shirt, who walks and sings us through the aftermath of Duncan’s death while posing the question: how many others met a similar fate without making history?

Led by State Opera South Australia regulars Pelham Andrews and Mark Oates, who inhabit a variety of historical players including the former South Australian premier Don Dunstan, the Chamber Singers, dressed in the dowdy greys and browns of the era, portray the drowning’s cascading impact across wider Adelaide, as the composer Joe Twist’s score veers into rock opera and disco.

Dunstan (Oates) explains in song the grind of parliamentary reform that, even after such an explosive event, is a three-year marathon of setbacks and compromise. This timely echo of today’s parliamentary horse-trading over the rights of queer people isn’t quite as plainly affecting as that inspired opening set piece (how could it be?) but there’s a feeling of bearing witness.

A brief moment of jubilation comes in the wake of decriminalisation in 1975; the music picks up to a danceable clip, the Chamber Singers shimmy and a slideshow of grainy photos of colourful parties and beaming friends hint at the liberating effect this legislative breakthrough had for generations of queer people.

But still questions of justice remain unanswered, from the New Scotland Yard report tabled in parliament which concluded Duncan’s killing was a “frolic” gone wrong, to the 1988 manslaughter trial that ends in acquittal for the former police officers charged. No one has ever been convicted over Duncan’s killing.

But that evergreen note of righteous anger is not the last emotion Watershed leaves us with. We return to a couple sprawled by the riverbank – it’s the drowning man and the Lost Boy in a tender embrace. As they kiss, the Lost Boy reprises his earlier, mournful refrain of “river don’t forget my name”, into something more gentle. It’s now a love song to those unforgettable anonymous encounters – the scent, the stubble, the long kisses. That, for all the danger, the drowning, the injustice, there is beauty in the beat.

After the curtain falls and the standing ovation finishes, I walk along the Karrawirra Parri on my way home, passing the spot where Duncan went under at about the same time of night half a century ago. Here there are no flashy lights — but it’s a hard place to forget.

Watershed: The Death of Dr Duncan continues at Adelaide festival until Tuesday 8 March