Review: L.A. Opera ends its pandemic hiatus with a triumphant, season-opening ‘Il Trovatore’

For 35 years, the Los Angeles Opera opening night, with its black-tie festivities, has, with one exception, heralded the fall season — whatever the temperature.

No one needed to be reminded Saturday night at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion why the seasons didn’t turn, turn, turn last year for the arts. But with a new production of Verdi’s “Il Trovatore,” autumn was meant to right itself.

For the record:

6:35 p.m. Sept. 20, 2021In an earlier version of this review, the photo caption misidentified Raehann Bryce-Davis as Tiffany Townsend.

The mood couldn’t not be celebratory. For the vast, mostly vaxxed, mostly masked audience, this was the first trip in a very long time to a theater to experience live opera fully staged. There were thrillingly big, bold voices. There was an exquisite soprano. There was a chorus, glorious. There was an orchestra sounding so rich and strong and colorful, even in the pit of an acoustically challenged hall, providing pleasure. There was potboiler Verdi.

A toast, then to L.A. Opera. It is a pandemic survivor, overcoming obstacles and not only the usual ones. The sets for the production, shipped from Europe, didn’t arrive in time. Because of the backup of container ships off San Pedro, new sets had to be built from scratch in 10 days, re-creating a similar feat 19 years ago when a labor strike hit the Port of Los Angeles.

From all appearances, the first-night performance went ahead without a hitch (which isn’t always the case with any production, any year). Even climate-changed nature appeared to be, momentarily at any rate, an opera fan. No heat wave. No smoke-filled air from fires blackening singers’ lungs.

But what the pandemic has ultimately wrought for L.A. Opera is a harder question to answer. This was not a normal opening night in several ways. The first music heard was the national anthem, sung by the audience through masks, which gave it a moving, muted mellowness.

There were no star singers but rather fresh talent. Much has changed in society during the pandemic, and clearly L.A. Opera, which has been an outspoken leader in addressing diversity in opera, is making a noticeable effort to have a cast that is racially and physically diverse.

It also selected an opera that, for all its popularity, has long been problematic for its racial stereotyping. It is the opera that has the anvil chorus, that treats the zingari (traditionally translated as Gypsies but now better translated by L.A. Opera as Romani) as the awful other, with their witches who cast evil spells and burn babies.

There is a lot to get around, and L.A. Opera chose a production from Monte Carlo by the Spanish director Francisco Negrín to solve those problems. He does so in part by making everything so dark and spooky you can’t easily tell what is what or why.

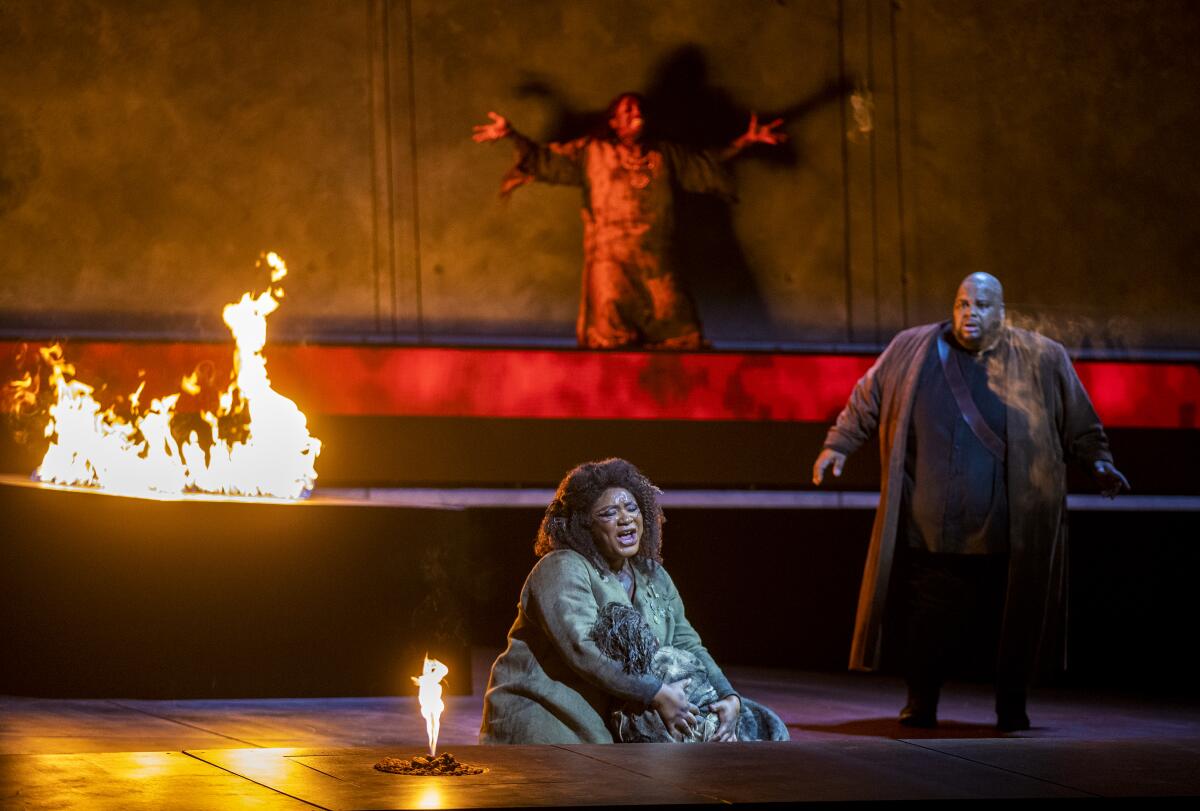

That Louis Désiré set so proudly built by L.A. Opera is a handsome, spare construction with moveable parts, including a tower that rises and lowers. Crevices serve a creepy crawly chorus. Fires come and go, as stark dramatic motive. The stage floor rises toward the rear, and everyone feels far away, adding to the dark, disturbingly ghoulish obscurity.

Every director these days makes some attempt at “Trovatore” redemption. L.A. Opera’s 1998 production set the opera in the killing fields of Bosnia. Negrín’s effort is to humanize Azucena, who avenges her Romani mother’s burning at the stake by stealing and incinerating the baby of a 15th century Spanish prince. In one of the libretto’s many incongruities, it turns out that Azucena mistakenly incinerated her own baby, so she has raised the Spanish one as her own.

This time, we witness “Trovatore” from Azucena’s point of view. Her charred child appears and reappears, as does charred momma. Centuries of terror and abuse toward the Romani appear to have created a community of grief, of which Azucena becomes for Negrín a symbol. The past cannot be escaped.

Too little of this, however, comes across on the stage. Poorly directed, singers semaphore conventional, unconvincing theatrical gestures that turn them right back into stock opera characters. All that fire and horror and angst feel stereotyped in their own right. Little is original visually and especially not the Robert Wilson-lite lighting effects of illuminated pillars.

Coronavirus may have silenced our symphony halls, taking away the essential communal experience of the concert as we know it, but The Times invites you to join us on a different kind of shared journey: a new series on listening.

Leaving the singers to their own devices is not, however, always such a bad thing in “Trovatore.” It’s often said that all you need are four impressive singers. In fact, five are needed, and L.A. Opera managed an impressive four.

Most striking is Guanqun Yu as Leonora, the love interest of both Manrico, the troubadour (Azucena’s “son”), and the Count (Manrico’s enemy and, we ultimately learn, his brother). Verdi made her a fiery heroine. Yu, on the other hand, is eloquent and understated and the most believable figure onstage. Her true, pure high notes become all the more meaningful for their lack of showiness. The sense of resolve and purpose she gives Leonora in sacrificing her life for love is inner strength rather than outer over-the-topness.

Limmie Pulliam’s Manrico is yang to her yin — physically, vocally and theatrically. He has a healthy, focused, ringing tenor that penetrates space but is never vulgar. He didn’t show much nuance, but neither did Verdi nor Negrin when it came to Manrico. If Pulliam required noticeable effort to sing softly, that effort had as touching an effect as the effort Yu needed to sound heroic.

Raehann Bryce-Davis might have been two different Azucenas. Onstage, she was reduced to stock traumatized motions to gain our pity, but vocally she filled the emotional gap. She relied on her resonant mezzo-soprano voice to reveal complex depths of character.

Baritone Vladimir Stoyanov’s modest Count showed his strength primarily in his sword play. But the powerhouse bass Morris Robinson, as Ferrando, the captain of his guard, rendered the Count’s army formidable. Leonora had a sympathetic Tiffany Townsend as her suffering servant.

James Conlon was, to little surprise, in his element with Verdi, the production’s publicity noting that the company’s music director has conducted more than 500 performances of Verdi operas throughout his career. He provided the singers his usual solid support and, when needed, some nudging in the direction of excitement. The orchestra played like it meant it, and the chorus sang that way as well.

Not for the first time, Conlon got the loudest applause, peppered with cheers of “maestro,” during the curtain call. This time he was not just the evening’s conductor but the symbol of a company back in action.

How back, you might ask? The risk factor may not be low enough for everyone to sit inside the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion for nearly three hours. Vaccination requirements allow for exceptions. (Those who are not vaccinated must show proof of a negative COVID-19 test within 72 hours of the performance.) Even though masks are mandatory for all throughout the evening, a couple in the row behind me took theirs off the second they reached their seats. Others within my view of the orchestra section let masks slip below their noses during the performance.

A check of the microCOVID Project risk calculator shows that attendance at “Trovatore” could be around half of your weekly risk budget. As an alternative, the performances on Oct. 3 and Oct. 6 (when Gregory Kunde will take over the role of Manrico) will be live-streamed for a fee.

'Il Trovatore'

Where: Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, 135 S. Grand Ave., L.A.

When: 7:30 p.m. Oct. 6, 2 p.m. Oct. 10

Tickets: $19-$292 to see in person, $30 to stream

Info: (213) 972-8001 or laopera.org

Running time: 2 hour, 45 minutes

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.