United Kingdom Guildhall School of Music and Drama’s Triple Bill: Guildhall School Orchestra / Dominic Wheeler (conductor). Live stream from the GSMD’s Silk Street Theatre and reviewed on 2.11.2020. (JPr)

United Kingdom Guildhall School of Music and Drama’s Triple Bill: Guildhall School Orchestra / Dominic Wheeler (conductor). Live stream from the GSMD’s Silk Street Theatre and reviewed on 2.11.2020. (JPr)

Production:

Director – Stephen Medcalf

Designer – Cordelia Chisholm

Lighting designer – Simon Corder

Assistant director – May Howard-Shigeno

Il segreto di Susanna (Susanna’s secret)

Music – Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari

Libretto – Enrico Golisciani

Countess Susanna – Olivia Boen

Count Gil – Tom Mole

Sante (non-singing) – Brenton Spiteri

Zanetto

Music – Pietro Mascagni

Libretto – Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti and Guido Menasci

Silvia – Ella de Jongh

Zanetto – Jessica Ouston

Rita (Two Men and a Woman)

Music – Gaetano Donizetti

Libretto – Gustave Vaëz

Rita – Laura Lolita Perešivana

Beppe – Thando Mjandana

Gasparo – Chuma Sijeqa

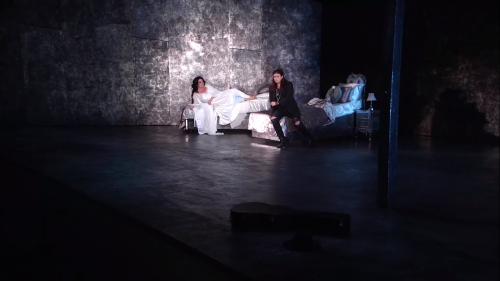

Well, how enjoyable this all was and perhaps something of a hidden gem as I would be interested in how many knew this live stream was available and watched as it happened (the only way to see a performance). Conductor Dominic Wheeler in an introduction explained that it was the Guildhall School’s first ever opera production like this and how what we would see was ‘completely live [and] unedited … with all the excitement and all the risks that entails’ to give the students ‘the chance to perform live in a socially distanced Covid-safe configuration’. Wheeler explained how ‘Our director Stephen Medcalf then devised – what we affectionately called – our kabuki [theatre] system for portraying moments of human contact.’ Asked in a Q&A (available on the GSMD website) Medcalf explains his ideas/inspirations as ‘Fantasies and dreams – very close together in many ways – tie together the three operas. What set us off was the Mascagni because there are so many dreams within this centrepiece. Sylvia seems to dream of this young man that she may have glanced at once in a street, who’s remembered her and who, somewhere in Florence, is also dreaming of that moment. Then of course this dream seems to come true. I suppose that we’ve expanded that theme of dreams to the other two operas. The set for all three works is, in essence, a bed, and the bed is torn in half – which is obviously emblematic of dreams and relationships that go wrong.’

Though not their original settings, Florence now links all three of the operas and there is ingenious use of black and white filmed montages which are dreamily projected at the rear of the stage to set the scene for each of them. These are in the style of some of the great masters of post-war Italian cinema, think Michelangelo Antonioni, Luchino Visconti, Vittorio De Sica, Federico Fellini, and others.

Wolf-Ferrari’s Il segreto di Susanna (Susanna’s secret) was premiered in 1909 and is a typical bedroom farce. Countess Susanna’s secret is a simple one (spoiler alert) and she just wants to smoke, something her husband, Count Gil, has forbidden her from doing. (Medcalf shows this by turning Gil into a puppetmaster briefly at one point). Gil is convinced by his own jealousy that Susanna has a lover who is a smoker who she sees when he is not at home. The bedroom looked like the type you would find in a plush hotel and the cast – as throughout the triple bill – were in contemporary clothes (apparently costumes were bought online). Wolf-Ferrari’s score is vivacious in an operetta-like way though there are the occasional overwrought passages for Susanna and Gil. It was played with great charm by the socially distanced young musicians spread out in front of the stage.

My only tiny criticism is that the overhead shots of Susanna as she lay on her bed were slightly voyeuristic and this was something that would be repeated in the other two operas. On the plus side I enjoyed the updating to have Susanna smoke marijuana and it made sense of lines like ‘its subtle vapour … lulls me into a dream’. There was a happy ending with Susanna and Gil reconciled smoking their joints and under the covers of their (separated) beds just like ‘Old Hollywood’ demanded of married couples! As the suspicious Gil, Tom Mole used a mature-sounding and well-focused baritone voice impressively; Olivia Boen was a pert and engaging Susanna, who seemed to relish her long drags on her ‘cigarette’; and Brenton Spiteri busied himself about as the mute servant, Sante. As throughout most of this triple bill the staging was clever and energetic and the choreography – helping to keep characters out of touching distance – was sublime.

Mascagni was basically a one-hit wonder and never really replicated the success of his 1890 Cavalleria rusticana and by 1896 his thoughts turned to creating another one-act opera that could be paired with it, though it has been Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci which proved more popular down the intervening years. Over the course of 50 minutes a couple’s romance – somewhat implausibly – flares up and peters out. It is Brief Encounter at its briefest!

A former courtesan, Silvia, falls instantly in love with a roving minstrel, Zanetto, who arrives at her hotel and who she recognises as the young man she had once seen and liked the look of. There is an instant mutual attraction, but Silvia must conceal who she is and her past life from him, and their relationship is doomed. In the end Silvia gives the youth up to continue his iterant life, admitting to Zanetto – also perhaps trying to convince herself – ‘I love you, like a child I want to save’. Silvia hands him a white rose and sings ‘By the time it withers you’ll have forgotten me.’

The plot is extraordinarily thin, but it is great that the young singers are given some melodramatic verismo to sing, rather than more Mozart which is all they sometimes seem to perform. This extended to Wheeler and his orchestra who empathised the wistful passion in Mascagni’s music. There is no overture and Mascagni opens the work with a delightful, a cappella, chorus. There are no formal arias and the closest Silvia comes to one is ‘Senti, bambrino’ (‘Hear me, my boy’) where Mascagni gives her music which sounds as if it was left over from Cavalleria rusticana. Until I read that Zanetto was a trouser role I thought the Guildhall School had gone in for some gender blind casting to put a new twist on the original plot! With her lank hair Jessica Ouston was a very convincing guitar-strumming, slightly androgenous, Goth and she used her plangent mezzo-soprano very intelligently. Ella de Jongh’s voice had a genuine dramatic edge but occasionally was a touch shrill, though hers was also a credible portrayal of an emotionally confused character who ends up totally distraught.

Donizetti’s Rita (otherwise Two Men and a Woman) was completed in 1841 but never performed in the composer’s lifetime and was premiered posthumously in 1860. It is a story (unsurprisingly) of a wife and her two husbands. Rita bemoans her lot and how her first one, Gasparo, was apparently drowned at sea and – assuming he was dead – she got remarried to Beppe. Then her house burned down and so did the village which means Gasparo who survived now believes Rita to be dead. Having made a new life for himself in Canada he returns for her death certificate so she can remarry. The rather dubious theme of Rita is ‘treat ’em mean and keep ’em keen’: Gasparo used to beat Rita to tame her (and we see how she still has the bruises) and now Rita takes it out on the hapless Beppe. When Gasparo comes back to the ‘Da Rita’ hotel, he teaches Beppe to stand up for himself and strike back. Unhappily marital – or any – violence against women (or men) is no laughing matter in the twenty-first century, and disturbingly when a beating is mentioned it is mimicked by what we hear from the orchestra.

Perhaps Rita was not staged while Donizetti was alive because he seemed to have reused so much of the music from his earlier L’elisir d’amore and Rita and Beppe are direct descendants of Adina and Nemorino. Also, the opera sags during a buffo duet for Beppe and Gasparo when they compete for Rita and it makes the opera seem much longer than 50 minutes and this could have been trimmed. This undermines the opera even though Dominic Wheeler conducted an outstanding account of the score, inspiring his young musicians to give their all. As in everything we heard, balance of the instruments and – Rita’s meanderings notwithstanding – tempi were well handled, with the orchestral accompaniment perfectly attuned to all three singers.

Near the end soprano Laura Lolita Perešivana sounded a little overparted but otherwise was a vivacious – though also sometimes over-excitable – Rita. As Beppe Thando Mjandana’s tenor voice was projected with ease and had a natural bel canto charm. Equally good was Chuma Sijeqa’s performance as a charismatic Gasparo. Sijeqa is a towering presence with a deep and rich (bass-?)baritone voice and it will be interesting to see what the future holds for him.

As an exclamation mark to Stephen Medcalf’s overarching concept of beds and dreams, Rita who had awoken at the start beside Beppe awakes at the end as if from a nightmare next to Gasparo!

Jim Pritchard

For more about the Guildhall School of Music and Drama click here.