United States Verdi, Il trovatore: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera, New York / James Levine (conductor). 15.10.1988 performance reviewed as Nightly Met Opera Stream on 7.7.2020. (RP)

United States Verdi, Il trovatore: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera, New York / James Levine (conductor). 15.10.1988 performance reviewed as Nightly Met Opera Stream on 7.7.2020. (RP)

Production:

Designer – Fabrizio Melano

Sets – Ezio Frigerio

Costumes – Franca Squarciapino

Lighting – Gil Wechsler

Chorus master – David Stivender

Cast:

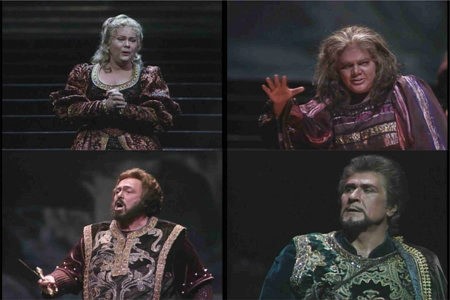

Leonora – Éva Marton

Azucena – Delora Zajick

Manrico – Luciano Pavarotti

Count di Luna – Sherrill Milnes

Ferrando – Jeffrey Wells

Ines – Loretta Di Franco

Ruiz – Mark Maker

Messenger – John Bills

Gypsy – Roy Morrison

The Metropolitan Opera’s stream of this 1988 performance of Il trovatore made my day. For most of my waking hours over the 24-hour span that it was available, I listened to glorious voices, which I had often heard live, singing Verdi’s wonderful music. After the initial viewing, I was content to listen although, truth be told, every time my eyes wondered to the screen, a new detail emerged in a characterization or the staging. I don’t recall seeing this production, and definitely not this cast, but I might have as I was a regular during those years.

Generally panned by the critics at its premiere in 1987, Fabrizio Melano’s production served as the backdrop to Joan Sutherland’s final appearances in the house. The set is minimal and consists of six groups of marbleized pillars, which were moved about to create vast spaces. Jets of flames shooting from the stage floor at pivotal points in the story line would still garner applause today.

Little of this mattered for streaming purposes, as Gil Wechsler’s lighting, or absence of it, meant all focus was on the singers. Large painted murals depicting storm scenes, volcanic eruptions and the like were visible, but little else. Solo spots and closeups of the singers afforded the opportunity to savor the visual delights of Franca Squarciapino’s sumptuous costumes, with even Azucena getting a bit of sparkle. Principals and chorus performed unimpeded by any discernible concept or stage direction.

To give Melano his due, it’s not likely that he could impose his vision of the opera on performers who dominated the stage by mere presence and vocal endowment. You would have had to put bags over the heads of the Met chorus to reign in their enthusiasm, even if they often had little to do but sit or stand about on the stage. With the benefit of hindsight, it’s a matter of counting blessings instead of sheep, as the song goes.

The cast fared little better in the reviews – Éva Marton’s dramatic soprano was not right for Leonora, Manrico was too heavy for the lyric-voiced Luciano Pavarotti and Sherrill Milnes was generally described as barking his way through his role. Only Delora Zajick, making her house debut as Azucena in this run, garnered praise.

Zajick was deemed a ‘useful addition’ to the Met roster, although it was noted that the quality of her voice and ‘certain details of craftsmanship’ were rarely found in singers who take on Verdi’s demanding mezzo-soprano roles. After a 45-year career, the great mezzo is planning to retire from the stage in 2021. Her final performances at the Met were to have been in Katya Kabanova in May 2020. Her last performances of Azucena opposite the Leonora of Anna Netrebko were at the Arena di Verona in 2019.

It was Éva Marton as Leonora, the role in which she made her La Scala Milan debut in 1978, that drew me to this Met offering: I had only seen her in heavier dramatic roles such as Tosca, Turandot and Elektra. If your definition of Leonora is floating high notes in ‘D’amor sull’ali rosee’, you were bound to be disappointed. If, however, integrity and intensity, both vocal and dramatic, are to your liking, Marton hit the mark. The middle and lower ranges of her voice were stunning, its innate metallic quality running to molten bronze. The camera catching her kissing the ring which contained the poison that she would later take was a subtle foreshadowing of what was to come.

Pavarotti had turned 53 just days before this event. By then, he could already be erratic as a performer, but this captures him in fine form and, moreover, wearing a handsome costume that flattered his frame. The sound of his voice is unmistakable, whether singing a melting legato or hurling ‘Di quella pira’ at the audience. I found his scenes with Zajick especially affecting. At his best, Pavarotti was a consummate artist and considerate colleague, and that is evident here.

The American Verdi baritone of his day, Sherill Milnes could chew up a stage and steal a scene even when not singing. (I once watched him catch the light in a wine glass that he was holding and grab a moment’s attention away from Marton while she was singing ‘Vissi d’arte’. Tosca’s stabs were particularly vigorous at that performance, and I wondered whether Scarpia would be on stage for the curtain call.) Here, he was as dashing as ever and in fine, if not fresh, voice for this stage of his career. The large shoes that he left behind at the Met were only filled when the late Dmitri Hvorostovsky arrived on the scene.

Bass-baritone Jeffrey Wells as Ferrando, captured at the start of his 25 years at the Met as a principal artist, was energetic, virile and clarion-voiced. Loretto Di Franco was one of the marvelous comprimarios active at the Met back in the day; this performance was just one of the more than 900 that she sang there over more than 40 years. To a large extent this valuable cadre of performers no longer exists, having been replaced by young artists in training. Their absence is mourned by many.

James Levine, looking impossibly youthful, was in the pit. He was then a demigod at the Met and had already began to work wonders with the chorus and orchestra. I always found him at his best when working with a soprano who possessed a voice of great amplitude and passion. Marton fit the bill. The orchestra was excellent throughout, but there just seemed to be a bit more elasticity and emotion to the sound when he and Marton breathed as one.

The curtain calls were long and boisterous. It was a time when confetti and pages of programs rained down on the stage. Bouquets were deftly tossed to Milnes. 1988 was the year that the Met began to tape performances prior to broadcast, rather than presenting them live as it had been doing since 1977. Surtitles would not come to the Met until 1995. It was another era, and nothing has made me yearn to be back at the Met more than this Il trovatore.

Rick Perdian

For more about Nightly Met Opera Streams click here.