Review: Eight Songs for a Mad King

King George III, despite having been a learned and enthusiastic sponsor of scientific and industrial progress, a faithful husband and father, and in many ways very liberal for his time (except pro-slavery, just saying), is basically famous for having gone mad.

That madness has been scrutinized, diagnosed, and mocked roundly in modern literature, film, TV, and theatre, and no doubt was similarly treated in the scandalous print media of his own time, like a 1700s reality show.. It’s gross, it’s sad, and it’s hypocritical, as we’re all really only one or two events away from breakdown.

So I felt uncomfortable at the start of last night’s show, seated outside the new(ish) RNZB Dance Centre. We peered through the many-paned windows, shifting to see around the frames, the poles of the marquee, and the heads of other audience members, trying to watch poor mad King George perform for us.

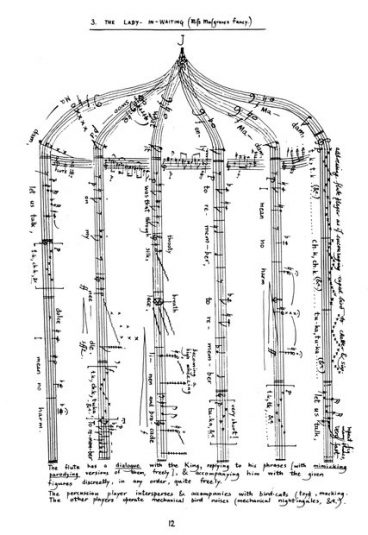

Eight Songs for a Mad King is a thirty minute operatic monodrama by Sir Peter Maxwell Davies. His friend, novelist and poet Randolph Stow, took Maxwell Davies to see a small mechanical hand organ that George III had owned. Apparently the king had tried to teach his captive birds to sing along, while his own voice was ravaged by incessant raving. An idea blossomed. Derived from eight of the songs the organ played, Maxwell Davies composed the piece, with Stow providing libretto based on real records of the king’s words.

Thomas de Mallet Burgess, General Director of NZ Opera, has acknowledged the challenge in staging exciting modern productions to attract a larger (and younger) audience, without losing the loyalty of longtime fans of the genre. Choosing to direct this show is extremely brave in that context, as it’s a confronting piece in subject matter as well as delivery. He split the audience in twain, one outside the windows, and one inside, with the outside half experiencing the performance through headphones. After completion of the piece, a short interval, and then the two audiences switched places for a repeat.

I started outside, and I think it was the best way around. With the headphones on and a very limited view of the action, I could only really focus on the audio. And dear God, what an experience that was.

Robert Tucker is wildly talented. In a conventional part, his deliciously resonant baritone warms your cockles, and his charismatic and sensitive characterisation brings a part to life. He is, truly, a brilliant operatic star.

As King George, his freakishly large range becomes apparent. Maxwell Davies intended the performer to illustrate King George’s mental state through an extended vocal technique, including howls, growls, whines and shrieks. With all senses dulled except my hearing, I sat almost immobilised by Tucker’s voice, tensely straining to glean from the libretto some idea of what he was going through to produce such noises. It was unnerving and confusing and what little I could see through the window only made it worse, as he appeared to throttle a flautist, smash a violin, and romance a light fixture.

I had a moment of sick disconnect. It felt like a parody… mental health is a complex and personal issue to be treated with respect and compassion, and this guy was rampaging up and down screeching like a caricature of “crazy”….. and we were all oohing and aahing delightedly like paying visitors to Bedlam, hoping to see a lunatic. How revolting. But then, this was written in the 60s, experimental and intended to shock, and based on historical records of King George’s condition, which also would have been very much of their time.

The first performance ended, and after a short interval, we moved inside. And here my discomfort subsided. Now able to see the performance as well as hear it, I realised that Tucker, under de Mallet Burgess’ direction, was genuinely trying to create from this part a real person. His George was struggling, yes, to love his people and his country. To articulate through his delusions feelings of loss, of confusion and pain, trying to explain to us that he fought his condition, and sometimes succumbed, sometimes won.

Some of the tropes were cliched; removing clothing, smashing things, howling like an animal, the minimalist lighting wrenched from orderly to haphazard… the score was scripted 50 years ago, so I can’t judge that era’s ideas of mental illness. In fact, Tucker found a truth within that. His expressions, his physicality let us see a real vulnerability, and a strength. And his voice, dear God… the publicity said he has five octaves, but truly I was dumbfounded. For a baritone to produce such strength in the higher registers, rather than just a weird falsetto… it’s a triumph. It’s possible that Tucker isn’t human. Just saying.

I know that de Mallet Burgess didn’t mean to parody mental illness, and he’s lucky to have found a lead with not only the talent for this vocal part, but also an actor willing to commit to it with sensitivity and kindness.

Hamish McKeich conducted the Stroma New Music Ensemble perfectly, and they delivered the score brilliantly, as well as being willing and able participants in our king’s delusions. The score is not easy – it’s dischordant and arrhythmic and disjointed. I especially appreciated Luca Manghi as a prop and puppet, playing flawlessly even as Tucker shook and spun him about. I could say more about the harpsichord themes and birdsong moments, but if I’m honest they faded into the background of Tucker’s wild and fragile performance. Suffice it to say, the ensemble was exactly as they should have been; immaculate and humble.

It’s always hard to stage productions with antique social perspectives. Madama Butterfly, for example, portrays devastating assault of an innocent girl, “married” to an American against her family’s wishes, then abandoned, dishonoured, and ultimately ending her own life as her child is taken to be raised by her foreign abuser and his real wife. Jesus, what the actual fuck? It’s a tragedy, and Puccini knew it was, but he still basically glorified it for the Likes.

This, sadly, is opera. But it’s also blockbuster movies these days, books, TV. We, like the visitors to Bedlam, like the audience last night, are eager voyeurs to others’ misery. The themes are enduring, human, and timeless. And we have been creepy peeping Toms for centuries.

What this means for opera, and for any art form which reproduces these classics time and time again, is that we need to find ways to make it topical. Otherwise the genres will genuinely fade into obscurity. As we shake off monarchy, will Shakespeare still have impact? Of course, because human themes endure, even though royalty goes out of fashion. So it is with opera, but those of us who love it must embrace new interpretations. It’s a duty but also a world of possibility.

In the back of my mind I feel like we have a responsibility to reframe these productions into something more appropriate to our new understanding of social issues. But King George was a victim of his time as well as his mind, and it’s equally important to show that time, and to highlight how these issues were seen and treated in our history, so we can be better. Mostly I’m really glad I got to see this weird and wonderful production, and also to see the audience around me, primarily older opera stalwarts, open themselves to confronting new styles of performance. I mean, we all fucking love La Boheme, but last night was a rollercoaster, and good on them for riding it with me.