Glyndebourne opens its season and marks the 150th anniversary of Berlioz’s death with a new production of The Damnation of Faust, directed by Richard Jones and conducted by Robin Ticciati.

Like many of Berlioz’s major scores, his version of Goethe’s play transcends the formal boundaries of genre, and his “dramatic legend” – part opera, part oratorio – was originally intended to be performed in concert. Bringing the piece on to the stage consequently presents its own series of challenges, and Jones’s solution to the work’s disparities is striking, if by no means ideally successful.

Firstly, he has added a spoken text, derived from Goethe, written by Agathe Mélinand, delivered by Christopher Purves’s Mephistopheles either at the start of scenes or over quieter orchestral passages, ostensibly to clarify the narrative and align it with Jones’s concept. Secondly, he and Ticciati have relocated the Menuet des Follets to the end, where it now forms a triumphal dance for Mephistopheles’ crew after Marguerite’s apotheosis. And finally, the score’s hybrid nature is reflected in the staging itself, which takes place in a lecture theatre, where the chorus alternately gaze down from upper tiers on the drama played out below, and descend to stage level to participate in it.

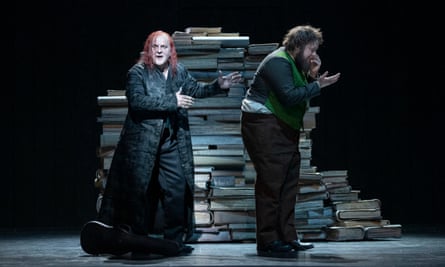

Jones’s interpretation, however, is hampered by uncertainties of tone since what he gives us is an inherently anti-Romantic vision of a deeply Romantic work. Allan Clayton’s Faust is a lonely bookworm with the unlikely job of teaching poetry at a military academy – where the cadets treat him with contempt – and his aspirations throughout are seen as either too naive or too fragile to hold up to reality. Julie Boulianne’s Marguerite is the put-upon barmaid at Auerbach’s bierkeller, dreaming of a life beyond everyday drudgery. The work can be viewed as a commentary on the seductive, demoniac power of music itself, and Purves’s sinister, sardonic Mephistopheles looks like Paganini, complete with violin case, while his sylphs have become the druggy inhabitants of a brothel.

Gradually, however, we realise that hell is the here and now, and that both damnation and paradise are redundant fictions. The additional texts allow Purves to identify the audience as “créatures d’enfer”, while Marguerite’s ascent to heaven is a figment of Faust’s imagination, for which Mephistopheles supplies the soundtrack by conducting his own devilish choir. Some of it is unnerving, some of it irritating, but the nihilism and cynicism of Jones’s vision all too frequently grate against the beauty, awe and wonder generated by the score.

Ticciati, an exemplary Berliozian, conducts with great beauty and a keen sense of dramatic pace. The London Philharmonic play with refined sensuousness of detail, while the Glyndebourne Chorus, augmented for the occasion, sound terrific throughout. Clayton sings with admirable ease and freshness of voice. His fervour in Nature Immense is beguiling, even though Jones has reduced the grandeur of the nature to a few bedraggled pine trees in the rain. Purves, slightly gritty in tone, is all malign irony and caustic wit. A superb actor, he speaks the interpolated text with great poetic eloquence and irony. The real revelation, though, is Boulianne, a distinguished mezzo with a velvety tone and a wonderful way with words. D’Amour l’Ardente Flamme, ravishingly done, is in many ways the evening’s high point. Musically, it is extremely fine, though Jones’s staging won’t be to everyone’s taste.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion