Maddening yet spectacular, prickling with insight but oh so laboured in execution, Stefan Herheim’s new staging of The Queen of Spades (1890) at the Royal Opera House pounds Tchaikovsky’s late masterpiece to a pulp as if resolved to break down its very enzymes. That’s Herheim’s habit, though he may not describe it that way. If you saw the Norwegian director’s Pelléas et Mélisande at Glyndebourne, or his La Cenerentola in Edinburgh, or his Les vêpres siciliennes at the ROH, you will know he cannot resist a concept, the bigger the better. This one dwarfs the Ritz.

Tchaikovsky’s fateful life is all there: his homosexuality, his fear of women, his possible suicide – not one glass of cholera on offer but an entire pub’s supply. His nightmare story becomes enmeshed in Pushkin’s tale: of a man obsessed with finding the secret of winning at cards. In his libretto, the composer’s brother, Modest, added layers to the terse original. Herheim constructs an entirely new fiction. Prince Yeletsky takes on the persona of Tchaikovsky himself, directing the action to baleful end. He embraces a male prostitute and rejects the advances of the angel of death, that black bird of prey which also represents womanhood (natch). The frenzied composer, or his chorus of clones, waves, emotes, bangs on a piano, in the act of creation, on and on.

Despite moments of perception, the heavy-handedness, at first tolerable, grows ever more burdensome. Let’s not mention the writhing trio of loincloth-clad Saint Sebastians, three too many. But there are vital, redeeming features. First seen at Dutch National Opera in 2016, this UK production has the matchless bonus of Antonio Pappano in the pit. The Royal Opera House orchestra blazes and caresses: agitated string attacks on the “three cards” motif; ferocious pizzicatos; woodwind curdling, yowling, seducing; brass sour and menacing. There is, too, top singing from the company’s enlarged chorus, further aided by Tiffin Children’s Choir and Boys’ Choir, confident and well drilled. How could anyone not want to witness such terrific music-making?

The staging looks good. Philipp Fürhofer’s handsome design, predominantly black and white, with empire-style crystal chandelier, potted palm and three french windows used to spooky effect, provides a backdrop to various visual feasts and follies. The cast is uneven. The British mezzo-soprano Felicity Palmer, now 74 but still vocally flexible, is potent and imaginative as the Countess, a role she first sang some two decades ago. As Liza, the Dutch soprano Eva-Maria Westbroek is thwarted by having to share her passion for the mad Gherman with a snooping third party – that wretched, voyeuristic composer. Westbroek remains a sympathetic presence, but on first night was not on secure form. Nor, as her Gherman, was the Latvian tenor Aleksandr Antonenko. He conveyed the lurching, compulsive behaviour of this antihero, but his tendency to tune his high notes, as if adjusting a violin peg, added an unnecessarily nervy quality.

The Russian mezzo-soprano Anna Goryachova made a sparkling Paulina, with the Swedish bass-baritone John Lundgren (Covent Garden’s recent Wotan in the Ring) an imperious Count Tomsky. The best singing came from the Bulgarian baritone Vladimir Stoyanov, making his house debut, as Prince Yeletsky/Tchaikovsky. The prince’s aria, roughly paraphrased: “I love you. I know you don’t love me. I’d do anything for you”, is perhaps the most heartfelt scrap of music Tchaikovsky wrote. Stoyanov sang with a pianissimo gentleness, beautifully accompanied. In its simplicity, it was as powerful a rebuke to directorial blether as a Gorgon’s gaze, but twice as tender. See The Queen of Spades in UK cinemas on Tuesday (encore, 27 January).

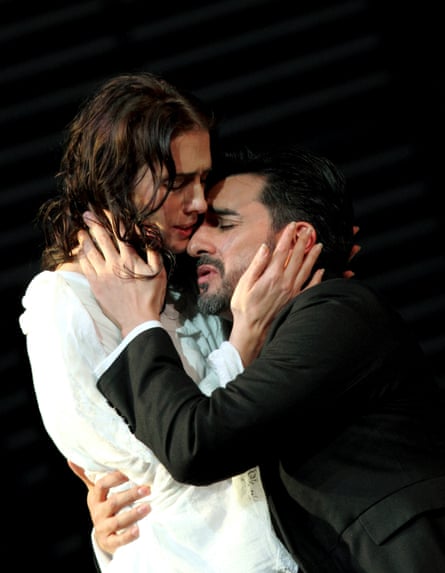

Also unmissable, live or at cinemas on 30 January (and 3 February): the Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho’s return to Verdi’s La traviata at the Royal Opera House, conducted by Antonello Manacorda. After an uneven start, voices not quite settled, pacing ponderous, the 16th revival of Richard Eyre’s sumptuous 1994 staging again worked its passionate magic. Jaho’s mix of defiance, fragility and savage honesty builds to an overwhelming finale. Charles Castronovo’s cool Alfredo finally melts. Jaho shares the role of Violetta in this run (whose double casting includes Plácido Domingo as Germont, here sung by Igor Golovatenko) with Angel Blue.

In a big week, London’s Kings Place launched Venus Unwrapped, a year-long focus on female composers. Hildegard of Bingen and Barbara Strozzi were in at the start, with so much more to come. I’ll be back. It’s a formidable exploration, not a rant.

Star ratings (out of five)

The Queen of Spades ★★★

La traviata ★★★★

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion