‘Siegfried’ at Lyric Opera: Amid witty optics, short-pants hero meets gravitas of Eric Owens

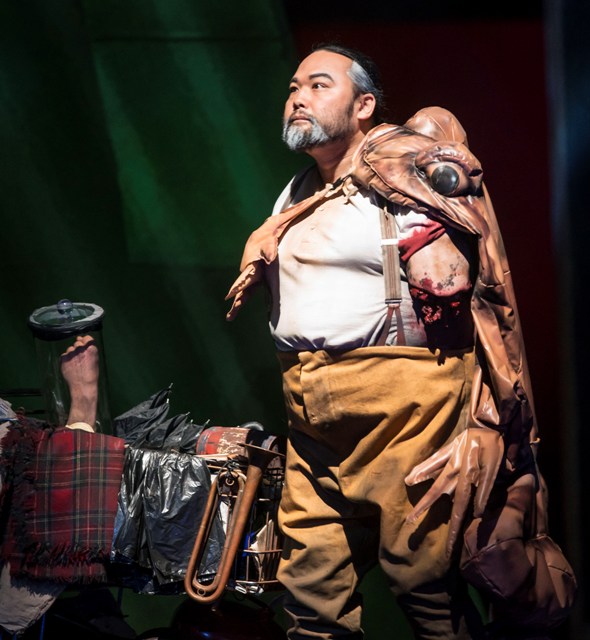

Wotan’s willful grandson Siegfried (tenor Burkhard Fritz) is growing up under maleficent Mime’s care; his dragon-slaying destiny awaits. (Lyric Opera of Chicago photos by Todd Rosenberg)

“Siegfried” by Richard Wagner at Lyric Opera of Chicago, through Nov. 16. ★★★

Nancy Malitz

With the premiere of Wagner’s five-hour ‘Siegfried’ under his belt, and thus three-quarters of the gargantuan 19th-century “Ring” cycle unveiled, the Lyric Opera of Chicago’s head man, Anthony Freud, must be feeling a bit like the besieged top god Wotan himself – guardedly hopeful and still determinedly in the game after unexpected calamity, subsequent creative scramble, and even a strike in the ranks that reflected contention in the realm.

Despite its stamina-testing length, this playful “Siegfried” elicited early roars of delight from a vocal, sold-out opening night crowd, boding well for the Lyric’s “Ring 2020” Festival scheduled for the end of next season, when “Siegfried” and the other operas in the four-part sequence will be presented in a trio of complete runs, an irresistible total-immersion opportunity that will doubtless attract Wagner zealots from around the world.

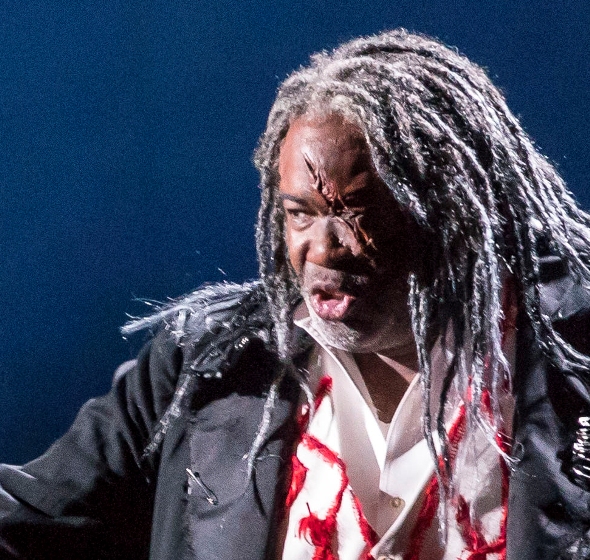

Bass-baritone Eric Owens, who originated the Wotan in this ‘Ring’ cycle directed by David Pountney and conducted by Andrew Davis, will carry it through to the Lyric’s ‘Ring 2020’ fest.

Set to star Eric Owens (top god Wotan), Christine Goerke (warrior-daughter Brünnhilde), and Samuel Youn (the nemesis Alberich) – among world-class Wagnerian singers at the top of their game – this “Ring” project was marked by early tragedy when its eclectic South African designer, Johan Engels, then 62, died at virtually the same moment the scale-model maquettes arrived in Chicago embracing his vision for the full massive undertaking.

Engels’ longtime collaborators, the veteran director David Pountney and Lyric music director Andrew Davis, carried the project forward with designer Robert Innes Hopkins, whose look for Parts 1 and 2 (the 2016 “Das Rheingold” and 2017 “Die Walküre”) did indeed seem akin to Engels’ audacious story-book conceit, his penchant for brilliant color and his touch of cheek: Now comes the third opera, “Siegfried,” which teased the audience with a shiny-red three-toed claw, beckoning from under the closed stage curtain, as if to say, “I’m Fafner the Dragon, and I’m ready to rumble.”

Siegfried confronts the fire-breathing dragon Fafner, whose claw makes a fleeting appearance before the show starts. Fafner’s fearful parts are manipulated by onstage actors.

The crowd rippled with mirth; then whooped happily at the end of the 85-minute first act, a good sign that people were on top of the details of this fairly complicated story about the brashly innocent young Siegfried, his questions about the birds and bees, his dangerously duplicitous guardian Mime, his one-eyed grandfather Wotan (in disguise) and a magic sword that needs mending if Wotan’s grand plan to save the gods has half a chance.

German tenor Burkhard Fritz, in his carefully paced American opera stage debut, starred as Siegfried, the fearless man-child who is Wotan’s last best hope. There’s a dragon that needs killing with that sword, and some gold that needs retrieving, and above all a female warrior-goddess who needs wooing. In this production, Siegfried begins his adventure while still clad in Charlie Brown style t-shirt and playground shorts, operating out of a room with a cage-like crib, his name scrawled childishly in huge letters on the wall above his drawing of a colorful dragon, and below a grinning sun. It is here that the man-child will forge his sword, apparently groomed for the task since early boyhood by an invisible, suggesting hand.

Time does have a way of collapsing in Wagner operas, but there was no getting around the fact that at the end of the night this charmingly juvenile Siegfried must have plausibly advanced through his adolescence into an encounter of gloriously romantic exuberance. The young man and his destined mate, the Valkyrie Brünnhilde, discover each other and will consummate their love, short pants or no.

The Lyric Opera Orchestra, which sounded superb in the aftermath of their season-threatening strike, delivered these blissful passages under the high-energy leadership of Davis with a conviction that nearly saved the production from the crucial weakness of a dopey-looking love scene between a boy and his shy, buttoned-up Brünnhilde. Both Fritz and soprano Christine Goerke, who played the Valkyrie, were in somewhat tentative voice on this particular occasion, as if testing the house, or the concept.

In any case, the scene was undermined. As the orchestra supplied some serious chromatic heat, with Wagner’s lush passages of rapture and sexual awakening filling the air, Siegfried and Brünnhilde lingered in their bright, childish, balloon-festooned cabanas. A young man who has killed a dragon and conquered magic fire is ready for grown-up love, I would argue, as is a former goddess warrior, now a human woman in full flower. Even allowing for some inner-child angle, the scene trivialized Wagner at his most extraordinary. I just couldn’t buy it, not even with Davis and his Lyric Opera Orchestra sounding ecstatically super-charged.

All the more important, then, was Owens’ deeply considered portrayal of Wotan, disguised as the Wanderer. Owens has lived inside the heads of operatic bad guys like Alberich and Beowulf’s man-eating Grendel, whom he has portrayed. It is no surprise his Wotan resonates with the wisdom of serious regard for his enemies. Mighty, ruefully wise, yet still cunning, he shows up on stilts (not a bad metaphor) and then engages in one last play, and yet one more, maneuvers for time, seeks advice, tries to warn, and finally lets go, knowing full well his own responsibility for the downfall of his realm and his line.

Owens’ masterful performance put a strengthening dramatic line under the comedy. So did Davis and the orchestra, whose enchanting “Forest Murmurs” scene, with the magical sounds of the trees and grasses gently rustling, sounded abundant and plush in the quiet. One might have wished for a few more strings, they played so beautifully, but the moment was pristine. Siegfried attempted to “speak” to the wildlife, trying first to play on a flute, then on a horn (assisted by the superb John Zirbel). The young hero seemed sweetly engaged; in all, it was the perfect idyll.

There were amusing directorial and design moves that seemed contemporary and fresh, tying the story’s threads nicely, and Wagner’s time to ours. Wotan’s realm – heavenly Valhalla – drops down like a window-washer’s platform from time to time, reminding us that Wotan is ever-peering, ever manipulating. In one such episode, Wotan seems to manipulate the charming coloratura soprano Diana Newman as the Forest Bird, who twitters timely info, puppet-like, to Siegfried, with a nod to “Chicago’s” Roxy on the knee of Billy Flynn (“…they both reached for the Gold!”).

Young Siegfried follows the fun kit’s do-it-yourself instructions to pump up the bellows, fire the forge and mend a shattered sword.

The express-mail delivery of Siegfried’s sword-forging kit – in installments, with Amazon-style logos on each box and hilarious “easy-to-assemble” diagrams – had the audience pealing with laughter. A troupe of mute but highly physical actors helped to facilitate this nifty sword assembly. They also managed the ocean of a skirt worn by the foreknowing goddess Erda (Ronnita Miller in her promising Lyric debut), and they maneuvered the enormous dragon Fafner. A growling balloon of many parts; the reptilian behemoth was brought to glowing life only to be punctured – and shrink back to almost nothing before our very eyes. (Patrick Guetti, whose dark bass served this outsize synthetic creature well, emerged from the dying dragon skin to appear briefly as a mere giant.)

Fafner’s not the only bad guy one could easily love in this production. There was Alberich, and Mime, too. Bass-baritone Samuel Youn, who first appeared as Alberich when the Lyric’s “Rheingold” was mounted, is now a lot angrier, mesmerizing as he doubles down on his smoldering grudges over the loss of the Rhine Gold and other humiliations courtesy of Wotan, who chopped off one of his arms. Pushing his cart full of junk and swearing mighty revenge, Alberich seemed emphatically credible to me.

And in his Lyric debut as Siegfried’s maleficent guardian, tenor Matthias Klink was a send-up as Mime, the Nibelung dwarf who pretends to be Mom and Pop to Siegfried while plotting his demise. The feverish, simultaneous activity of Siegfried, who’s forging his sword, and Mime, who’s brewing up a potion to kill the boy – just as soon as the young hero has killed that dragon – amounts to a clever side-by-side show. When Siegfried becomes a mind-reader, and Mime is forced to protest the boy’s “lyin’ ears,” there’s a good bit of laughter to be had.

Related Link:

- Performance location, dates and times: Details at TheatreInChicago.com