by Steve Cohen

In

the first article in this series (click

here to read) we saw how Verdi's early operas focused on oppressed

people, and his melodies became theme-songs for the Italian independence

movement. Some revisionist historians have challenged the connection

of Verdi to the struggle. They claim that he abandoned the cause by

1850. But they should check their sources more carefully.

In

the first article in this series (click

here to read) we saw how Verdi's early operas focused on oppressed

people, and his melodies became theme-songs for the Italian independence

movement. Some revisionist historians have challenged the connection

of Verdi to the struggle. They claim that he abandoned the cause by

1850. But they should check their sources more carefully.

From our distant vantage point the Risorgimento may appear to be a steady advancement. In fact, it was an uneven progression and at the end of 1849 the movement stalled. Austrian troops recaptured Venice and restored the princes who had been expelled from central Italy. French forces occupied Rome. The Risorgimento leaders Garibaldi and Mazzini fled into exile; in 1850 Garibaldi was a fugitive in New York City.

Italy remained divided. To travel across the country you had to change coaches at a series of international check points. Italians resented the inconvenience, and the fact that they were under the command of foreigners.

A decade later a diplomatic aspect emerged, led by Count Camillo di Cavour of the House of Savoy, and in 1861 the Kingdom of Italy was proclaimed in Turin by a parliament that included elected representatives from almost all parts of Italy. Not until 1866 was Venetia freed from Austrian rule, and it was 1870 before Rome was severed from Papal control.

After 1849 Verdi had no opportunity to converge with leaders of the revolution. What's more, he was a private man who rarely reached out to others. "Please leave me at home at peace" he wrote to a colleague. Verdi focused on his living-together relationship with Giuseppina Strepponi (a close-knit liaison, because she was shunned by society), and on an estrangement from his religiously-observant parents who disapproved of Strepponi: "For my greater peace of mind...I intend to be separated from my father in my residence and in my business."

Verdi wrote to the father of his late wife, "What harm is there if I live in isolation? If I choose not to pay calls on titled people?...In my house there lives a lady, free, independent, a lover like myself of solitude, like myself possessing a fortune that shelters her from all need. Neither I nor she owes anyone an account of our actions."

Amid all this, he concentrated on his craft. This is a remarkable list of what Verdi composed during that period from 1849 to 1871:

Luisa Miller (1849)

Stiffelio (1850)

Rigoletto (1851)

Il Trovatore (1853)

La Traviata (1853)

Les vêpres siciliennes (1855)

Simon Boccanegra (1857)

Aroldo (1858)

Un Ballo in Maschera (1859)

La Forza del Destino (1862)

Don Carlo (1867)

Aida (1871)

Most of the operas in that list are still popular, and respected, two centuries later. He was 37 years old at the start of this span.

Many of these alluded to Verdi's personal life.

Luisa Miller is an intimate drama of domestic life. In its dealing with bourgeois hypocrisy, it presaged Traviata. Despite a lack of battles and big choruses, Luisa became a popular success, staged in Naples, Rome, Venice, Florence and Milan. Then it had an American premiere at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia in 1852.

Next came Stiffelio, a philosophical drama of hypocrisy concerning a Protestant minister with an adulterous wife. As his private agonies clashed with his public responsibilities, this brave cleric publicly, from his pulpit, forgave her. Verdi wanted Stiffelio performed in modern dress, to indicate its immediacy. Censors eliminated the church scene and the contemporary setting. Later productions made even greater cuts. Verdi angrily withdrew Stiffelio from circulation but reused parts of it for his Aroldo, set in 13th century Anglo-Saxon England. Discovery of the composer's original manuscript in 1992 led to a Metropolitan Opera restoration which is worth seeing when it next appears.

Four months after Stiffelio, Verdi premiered his Rigoletto, the story about the licentious Duke of Mantua, his court jester Rigoletto, and Rigoletto's sheltered daughter Gilda. Included are abduction, rape and murder. It is a compact opera, dark in tone, featuring bassoons and lower strings. The last-act quartet is innovative, as four characters sing dissimilar types of melodies in different rhythms. A vivid storm scene includes lightning flashes by flutes and the moan of the wind by the humming of choristers.

The Venice Gazzetta commented on "the oddness of the subject and novelty in the music....The instrumentation was stupendous, admirable; the orchestra speaks to you, cries out to you, it instills passion in you. [But] we cannot in good conscience praise such taste." The Lombardo Veneto wrote "It is an unbroken fabric of instrumentation which either speaks softly to your soul, or awakens you to pity, or horrifies you." L'Italia Musicale praised Verdi's turning-away from "grandiose ensembles, big arias, noisy finales. [But it leaves us] empty and disgusted at such a horrendous and nauseating spectacle."

(The most recent opera by Wagner, who was Verdi's age, was the grandiose, big-ensemble Lohengrin.)

In an expression of Verdi's personal feelings, the title character is scorned by court society and he becomes a subject of sympathy. We root for him, despite his participation in evil. We care more about him than about his innocent daughter.

Il Trovatore followed just a few months later, in January 1853. Verdi instructed his librettist to avoid standard forms like "cavatinas, duets, trios, choruses, finales." Despite his expressed desire, Verdi did compose duets and trios for Trovatore, albeit with more vigor and personality than in conventional Italian operas. Every principal has hummable arias which define their characters, and so does the chorus as it works on its anvils. In particular, the music stresses intensity and confrontation, which reflects his conception of his leading character.

The heroine of Trovatore is a woman despised by society. This is the gypsy Azucena, assigned to a mezzo or contralto to denote the dark way she was viewed by the world. Verdi wanted to name the opera after her, rather than the troubadour. Verdi wrote that it was "the principal role; finer and more dramatic and more original than the other." Leonora, the soprano, is characterized by a soaring, aspiring, angelic quality whereas Azucena's melodies are direct and blunt. Verdi obviously felt a personal connection to the plight of his leading woman.

In Paris in 1852 Giuseppe and Peppina attended a performance of Alexander Dumas fils's La dame aux Camélias (The Lady of the Camellias) and he immediately decided to turn it into an opera. Verdi wrote a letter saying "it will probably be called La Traviata (The Fallen Woman). A subject for our own age." He wanted it set in the present day, with a "realistic" production. The composer was not being subtle.

Police censors forced the setting to be changed to "circa 1700" yet the opera still was denounced for excusing immorality. Despite the indecent story with a tragic ending, audiences walked out of the theater humming Libiamo, Ah fors' è lui, Sempre libera, Dei miei bollenti spiriti, Di provenza Il mar and Addio del passato. That's six hits songs in one show, far more than any Broadway or West End creation in the 21st century.

And that's where Verdi stood at the age of 40, in the midst of his most productive years- his partner shunned, his choice of subjects criticized, while his operas were the most performed in the world. My hunch is that the Italian masses supported Verdi's free-thinking independent actions as well as they loved his music, even though the ruling class disapproved. Or maybe because the ruling class disapproved.

In the next article, we'll discuss Verdi's respect for words, and his obsession with adapting exceptional literature.

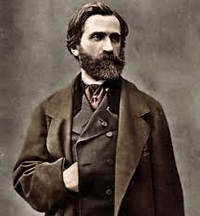

Photo of Giuseppe Verdi