A strange and fascinating piece it is, The Golden Cockerel. The last of 15 operas composed by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, it emerges from the world of Russian folk tales, in this case a fable by Alexander Pushkin. When Rimsky-Korsakov and his librettist, Vladimir Belsky, wrote their opera in 1906-07, it was viewed as a work of political satire, created as it was in the aftermath of the Russo-Japanese War (which humiliated the Russian military) and the cataclysmic social unrest that rocked Russia in 1905. Nervous Tsarist censors demanded so many changes that the composer preferred to leave it unproduced, and it was not staged until the year following his death — and then in a toned-down version. Santa Fe Opera unveiled its first-ever presentation of The Golden Cockerel on Saturday night, in a radiant production overseen by Paul Curran that conveys the work’s folk aspects with loopy charm and visual splendor before going a bit off the rails trying to underscore its relevance to today’s international politics.

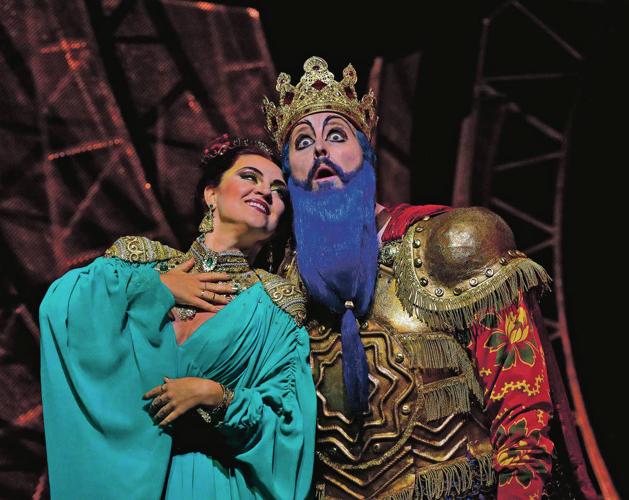

The production is beautiful to behold, with credit for sets and costumes going to Gary McCann. Two basic sets — one for the first act, one for the single span of the second and third acts together — are born of the same Futurist-Constructivist sensibility. Each involves an abstracted metal framework that reaches deep into the stage. The first towers high on the audience’s left and sweeps steeply down to the area of the main action, resembling the three-dimensional graph of some advanced mathematical function; the second looks more like a roller coaster. They support a gauze covering onto which projections (by Driscoll Otto) are superimposed, sometimes in motion, sometimes stationary, to portray landscape details, private dreams, or the cockerel itself (which only ever exists as a projection), or sometimes just to provide a wallpaper-like background. The costumes are stunning: closetsful of vivid folk-inspired dresses, cloaks and headgear sprung from a lavishly chromo-lithographed children’s book, their flamboyance optimized by Paul Hackenmueller’s lighting design.

Tsar Dodon, who would rather sleep than rule his realm, is a Peter Pan of a monarch. (His name is amusingly derived from the French phrase faire dodo, infantilized slang meaning “go beddy-bye.”) In the opening act, he is dwarfed by his super-sized throne. Remember Lily Tomlin’s Edith Ann in her great big rocker? Here, though, the character perches on plush royal vermilion surrounded by gold. Later, he sets off to war on a similarly scaled toy horse on wheels, which he can only mount backwards because of his girth; it takes a handful of courtiers to pull him along. He is a foolish leader who accepts ridiculous military advice from his stupid sons, who are so inept that they kill each other on the battlefield by mistake. He ends up entrusting the security of his nation to a Golden Cockerel, a watchdog of a bird (a gift from an Astrologer) whose call — “Kirikikuku” — is supposed to signal a border incursion from the neighboring country. The Tsar is seduced by the Queen of Shemakha, who is apparently in league with both the Astrologer and the Cockerel; and, after an altercation with the Astrologer, he is pecked to death by the bird, leaving the Queen to rule her newly acquired nation.