Without rage, there would be no opera. Many of the most celebrated arias are composed of a tincture of anger steeped in a bubbling spume of melody. Strauss’s Elektra, though, delivers an especially caustic solution, a single 100-minute act of terrible, scouring fury. Vengefulness propels the title character; revenge redeems her. Howls are answered, a murderous itch is satisfied. In the Metropolitan Opera’s new production, the director Patrice Chéreau forces us to confront our most vicious tendencies, and acknowledge the thrill of seeing appalling wishes get fulfilled. He has stripped away the usual trappings of ancient tragedy — robes, helmets, blood, and ruined grandeur — and let the music explode in a setting of fearsome plainness.

Chéreau created this production for the summer festival at Aix-en-Provence in 2013, but died before it landed at the Met. (Vincent Huguet acts as his posthumous proxy.) The set designer Richard Peduzzi imprisons the stage in an austere compound made of stucco or concrete — something thick, rough, and heavy — sealed off from the outside world by a sliding steel door. We are in the courtyard of a surrealistic palace, a place of De Chirico–like blankness. There is an arch, a staircase, a stone bench, and little more. Within these walls, Chéreau conjures the kind of lethal claustrophobia that Quentin Tarantino can only dream of. Inside, the women come and go, dressed in clothes they might have scavenged from an aid truck but are in fact by Caroline de Vivaise. Nothing quite fits, and costumes merge into a palette of dun and grey.

What gives life to this bleak world is music that is both subtle and fierce. The conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen draws from the Met’s sumptuous orchestra a range of shadows, highlights, and gaudy violets that would do Caravaggio proud. Elektra is the composer’s outer planet, the point beyond which music could only spin off into nothingness, and civilization with it. It’s easy to overdo the extremes. With its ceaseless gallop and snapping, surging harmonies, the score lends itself to hyperbolic performance, but Salonen resists the temptation. Instead, he finds intensity in restraint.

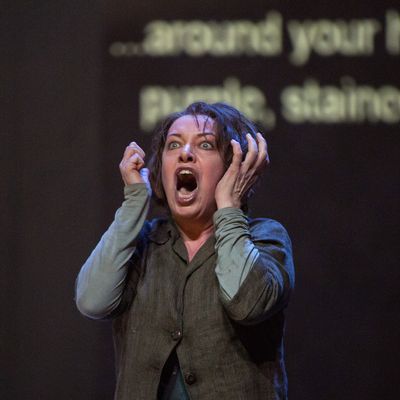

This requires a certain amount of revisionism. Strauss and Hoffmanstahl present the characters as an assortment of unappealing types. There’s the unhinged Elektra who craves her mother’s and stepfather’s death; Chrysothemis, diplomatic and dithering; and Klytämnestra, the treacherous virago who deserves her fate. Chéreau and Salonen together have scrambled these attributes, or rather dialed them down into the range of creepy realism. Nina Stemme makes Elektra’s bloodthirstiness seem almost rational, Waltraud Meier brings poise and grace to Klytemnästra, and Adrianne Pieczonka gives an unexpectedly steely spine to Chrysothemis. Strauss’s vocal writing can tempt singers to treat every syllable as a proclamation, each note a hatchet blow, especially at a ponderous pace. Salonen doesn’t allow that to happen. He keeps tempos brisk, so that Stemme has the breath to float long, pliant phrases. When she first opens her mouth, it is to call her murdered father, Agamemnon. Even at high volume, Stemme sings the passage like an inner thought, lofted onto the wind. Later, when Elektra’s long-lost brother Orest returns, and the brassy charges dissipate, Stemme lets her voice bob on melancholy, glittering strings.

Even as the music soars, Huguet (channeling Chéreau), keeps the action close to the ground. The singers sit, crouch, lie, or cower, so that the best view is from above and audience members seated in the orchestra must crane to see what’s going on. In the midst of all this brown, hunched realism, slowly a suspicion forms that the stage is really an asylum, and we are watching a story that the inmates tell themselves. Maybe that’s why in the silence before the opening downbeat, one maid sows invisible seeds while another sweeps up. Their separate worlds overlap at the edges, where they calmly undo each other’s work. And perhaps that’s why Eric Owens sings Orest with such ghostly, elegant cool: He is not just a bringer of revenge, but a beautiful apparition, there to sublimate our fury into song.