Seth Colter Walls: Hello, Jason! We both saw Thursday night’s premiere of a new production at the Metropolitan Opera – celebrated visual artist William Kentridge’s new take on Alban Berg’s modernist 20th century masterpiece, Lulu. You cover the art world; I write about music. (And I interviewed Kentridge during rehearsals at the Met, last week.) So the idea here is that we’ll (hopefully) be able to hit on all sides of what amounts to a crossover high-art phenomenon in New York’s fall season.

I won’t belabor my own headline-takeaway from last night: I loved it, top to bottom. (Marlis Petersen is a great Lulu – and the rest of the cast ranged from passable to excellent.) I’m probably going to see it again – perhaps in a movie theater, when the Met simulcasts a Saturday matinee performance on 21 November.

I went into the opera with an appreciation for Berg’s dramatic achievement, in adapting the two scabrous, bleak Lulu plays by Frank Wedekind. (Those dramas tell the story of a much-desired young woman who leads a series of admirers to grim ends, before she is in turn killed by Jack the Ripper.) More than that, though, I admire the composer’s musical achievement – fusing Schoenberg’s 12-tone method with sultry late-Romanticism.

While I was a fan of Kentridge’s first collaboration with the Met (directing Shostakovich rarity The Nose), I was concerned that some of his tricks – all those paper-and-ink video projections and animations – might not work as well in presenting the sometimes complex stage action of Lulu. Or that those tricks would become stale over a four-hour opera. Happily (for me), none of that came to pass.

But what about you? Though I expect we’ll both give judgments from our respective critical beats, I’m also interested in your experience of the music. (In New York anyway, this repertoire is thought to be a hard sell, at least to the regular classical ticket-buying audience). I know that, as I did, you saw the Met’s final presentation of the foregoing production in 2010. So how did this new version hit you?

Jason Farago: Like you say, this Lulu is less hyperactive than Kentridge’s The Nose. For good reason. The Nose, Shostakovich’s 90-minute one-act, is pretty inert dramatically, and Kentridge recharged it with a battery of imitation Soviet film reels and wild costumes. Lulu, by contrast, already has an almost overwhelming dramatic intensity, borrowed from Wedekind’s decadent plays. So Kentridge has not made too many radical changes to the book: although he’s added a pair of mute characters, notably a dancer writhing inside a piano who remains onstage throughout, he’s played it pretty faithfully. The invention is in the images.

But I ought to get my personal headline out here, too: this is a landmark production in the history of the Met. Along with the shorter Wozzeck, Lulu is very possibly the most important opera of the last hundred years (though Berg left it unfinished upon his death in 1935). In every way, Kentridge’s version supersedes the Met’s previous production – a competent if staid one from the 1970s, when Lulu was finally presented in a full-three act version, with the last act’s orchestration completed by Friedrich Cerha.

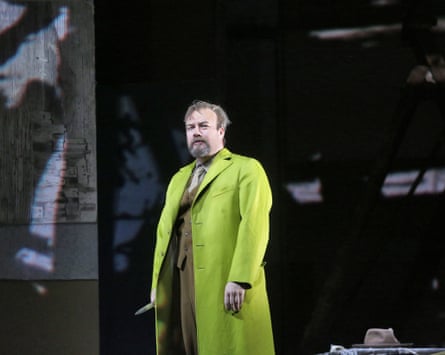

Petersen nailed the title role last night. She first hit it big in New York when she stepped into the role of Ophélie two days before opening night of Hamlet in 2010 – but Lulu is her part. And she can actually act! She pouts, she prances, she transforms from gamine to hag. She’s announced this will be her last Lulu, and I understand why she’s giving it up. It’s a young singer’s role, and you can only do such devastating material so many times. Which means: if you want to see one of the great Lulus, get to New York now.

Seth: I like what you said about the invention being in Kentridge’s images. But it’s not just that his images are cool (though they are), it’s that they serve the story well on the level of stage action. There’s a lot of ushering folks on and off the stage, which can get confusing if the director is more interested in a “take” than in doing Berg’s opera.

Unlike a lot of “radical” stagings of Lulu, this one doesn’t try to add any new director’s “ideas” to the opera – it just tries to get at everything that Berg’s music and drama contains. (The opera is plenty sophisticated already: about sexual politics, about capitalism, about human relations generally. It wasn’t one of philosopher Theodor Adorno’s favourites for nothing.)

So while a description of this production can sound like one of those meddling-director’s efforts to graft new meaning onto an old work, Kentridge’s great achievement here involves using his considerable skills as an artist to present this piece clearly. And the reason Kentridge’s image factory winds up being a great fit for the material is that this opera is about image-making: the fantasy images of Lulu that the succession of men — as well as her lesbian admirer, the Countess Geschwitz – construct in lieu of actually knowing her.

Jason: Precisely. At a few instances we see Kentridge slather black ink in a dictionary, close the book, and then reopen it – creating a Rorschach inkblot. Rorschach, a Swiss, was a contemporary of Berg, and the inkblot is of course an abstraction that says more about the beholder than it does about the creator. So is Lulu. “I’ve never pretended to be anything but what men see in me,” she sings in act two. The men in her life give her different names – Mignon, Eva, Nelly – and no one, not even her putative father, knows much about who she really is. Only the woman is unknowable, of course; we could use a real feminist production of Lulu.

Seth: It’s strange, by the way, that the Met’s English titles didn’t translate the explicitly feminist angle of the Countess’s final scene. In the German libretto I’m looking at right now (from Pierre Boulez’s recording on Deutsche Grammophon), she says she’s going to law school in order to Frauenrechte kämpfen (“Fight for women’s rights”), given all she knows about the ways women are abused. But the Met titles just rendered it as “going to law school” or some such? That was weird.

Jason: Whoa, it’s crazy that you caught that too. I only noticed because by the third act I had switched the little Met titles in front of my seat from English to German. Which, Gott im Himmel, sounds like the most pompous thing in the world to say, but let me explain: Kentridge was projecting the English text directly onto the stage, on screens papered with dictionary pages. Language is a key element in Kentridge’s artistic toolkit, and meaning is often slipping away: he likes to project pithy, off-center phrases, such as “Hearts than move mountains” or “Here you’ll find peace” – here being the grave, I suppose. Most of the ink paintings in this production are done on pages torn from an old Oxford English Dictionary, though there’s also a foreign language dictionary projected at a few points: I’m not sure if it was Afrikaans (Kentridge lives and works in Johannesburg) or Dutch (this production first appeared in Amsterdam).

I happen to think last night’s production marked a big step forward for Kentridge. He first came to prominence for his hand-drawn animations – above all the doleful Felix in Exile, completed in 1994. In those animations, Kentridge would film one drawing, then erase it, draw the next, film it, erase it … such that, when the animation was projected, smudges and remnants would remain. The films bore the mark of their own making, their own history. Which felt especially powerful in the first years after the end of apartheid.

He’s moved past that now, and the projected images take the form of ink paintings on dictionary pages, or else woodcuts and linocuts in the manner of German expressionism. Things were moving fast last night and I didn’t catch every reference, but there’s a pendant exhibition of Kentridge’s preparatory materials now on view at Marian Goodman gallery. None of the drawings there are named, but Kentridge employs clear quotations of Weimar-era painting – Christian Schad’s 1928 painting Sonja, for instance – and even depicts Berg himself, looking very louche and Oscar Wilde-like.

Seth: I definitely need to check out that show. But maybe not until I go see Lulu again. There are several great performances in this cast. Bass-baritone Johan Reuter gave a dramatically nuanced performance as Dr Schoen: sometimes conniving, sometimes playing the victim. And tenor Alan Oke’s multi-role part – including the Prince in act one, and the Marquis in act three – was a revelation. (While projecting an attractive, house-filling sound in both parts, he was buffoonish in the former, and menacing in the latter.)

Given the quasi-grindhouse nature of the first two acts, there’s sometimes a tendency to make Lulu seem all-powerful, like a one-dimensional femme fatale. And when Lulu is having an argument with this or that admirer, sometimes the acting just goes full-throttle intense at the beginning of a scene, and stays there. But Petersen’s interactions with Reuter in the first and second acts had an appealing ambiguity: as though both characters were trying to figure out exactly what kind of spell they were casting on one another.

Jason: Unknowability is at the heart of this opera. It starts right in the first scene of act one, when Lulu is having her portrait painted. In Wedekind’s play, Lulu is dressed up as the clown Pierrot, a stock character from commedia dell’arte. Here, we see Lulu posing in a low-fi, Kentridge-standard getup: a giant paper glove on one hand, some ink drawings on her dress. Additional ink drawings get pinned to her as the scene goes on. But although Lulu hangs onto the painting until her grim end in a London garret, we never actually see it as an object on stage; it appears as a projection, and it’s never the same twice.

A fragment from the outfit Lulu poses in stays pinned to Petersen throughout much of the rest of the opera: a square sheet of paper inked with a crescent and a dot, which sits on her right breast. It’s a marker of femininity, of course, but an abstract one. It’s so spare, in fact, that it barely looks like a breast at all – it’s more of a sign or a symbol than a representation of the female form. (A musical symbol, actually. It’s an upside-down painting of a fermata: the bit of musical notation used to indicate a dramatic pause.) Lulu is always carrying on her body this marker of abstraction. Unknowability again: she recedes from a woman into a free-floating sign.

One other thing: Given that Berg’s music was banned by the Nazis, it’s hard not to see the symbol pinned to Lulu’s chest as a harbinger of other, more vicious markers pinned to clothes in the 1930s and 1940s. Joseph Goebbels loathed 12-tone music, which he called a symptom of “the Jewish intellectual infection [that] had taken hold of the national body”. Perhaps I’m being too literal. But images of Nazis – Leni Riefenstahl, for one, and also Hermann Goering – appear in both the projections at the opera and in Kentridge’s preparatory drawings.

Seth: I noticed Kentridge’s drawing of Berg himself haunting Alwa’s solo feature, in the third scene of the first act. But I did not clock all the other extra-narrative references in the projections. (That’s one reason I’m going back!) Another great thing is that, in this production, the act one painting can loom as large for the audience – thanks to the projection – as it does for the characters.

Jason: And it can mutate in a hundred different ways. Lulu appears dressed or nude, childlike or feminine, with a boa constrictor around her neck at one point. Some of the projected paintings are, by the way, the most erotic artworks of Kentridge’s whole career. At one point he projects a painting of Lulu as an odalisque, bare bottom high in the air.

Seth: In a way, Berg’s multimedia interest was too advanced for the operatic production practices of his day. He called for a silent film to be showed during the act two orchestral interlude, and a lot of productions just ignore this. But Kentridge actually made the film (starring the pianist-avatar version of Lulu), and it works fantastically well. For me, it really connected the two different halves of the second act in a way I’ve never experienced before.

Jason: Well, in fairness, there were attempts to introduce multimedia into the theatre of the Weimar era. In the theatre of Erwin Piscator, for example – whose production of Hoppla, Wir Leben!, from 1927, featured projected films making use of high-speed montage. Or Meyerhold, in the Soviet Union, was experimenting with projections on stage. But you’re quite right that the film component of Lulu has proved a step too far for most directors. Last time I saw Lulu, in 2010, they just left it out. It’s funny to think that the Met needed to bring in a visual artist to do what opera directors considered avant-garde nearly a century ago.

And the film is one of the strongest parts of this night. It depicts Lulu’s time in prison, after murdering her third husband (the first two have already kicked it, one from a heart attack, one from a razor to the throat). An actor in a Louise Brooks bob appears in a mugshot alongside a drawn version of Lulu; we see her try to seduce the prison doctor. And then, in giant letters: DIE SCHULD. Which is the German word for guilt, but also, as everyone in the Greek finance ministry can tell you, also means debt. Money, sex, murder: it’s all one.

Seth: So, we’re agreed: this is a monster show, and everyone needs to know.

Jason: And goodness knows the house needs one. Since 2006, when Peter Gelb became general manager, the Met has been promising more serious and more ambitious stagings than the horns-and-breastplates showcases of a previous generation – and yet often failing to deliver. This Lulu stands alongside a few other productions (Willy Decker’s La Traviata, Phelim McDermott and Julian Crouch’s Satyagraha, François Girard’s Parsifal) as a rare case when the Met brought it.

Seth: I think there are a couple more successes in the mix, too. But it’s true that the recent track record has been uneven. Partly, this has to do with the way that the Met serves many different audiences, with different tastes. (Opera lovers are thought of as a uniform cadre, in the broader cultural conversation. But saying you like opera is like saying you like books. Do tell! Which ones?)

People who are afraid of “12-tone” (or “atonal”) music really owe it to themselves to hear this particular production. For this run, conductor Lothar Koenigs is stepping in for Met music director James Levine, at short notice. The sound he gets from the Met orchestra leans hard on the score’s Romantic attributes. (Which makes sense, since that’s generally how Levine has conducted Berg at the Met, over the decades.) My notes from last night are strewn with exclamations about various sumptuous effects, like the saxophone playing that sways through some of Lulu’s music in the first act, or the lushness of the string music that stalks the Countess, later on. It’s a glorious performance, on a level of sound. And Petersen has the vocal toolkit Berg wanted for this role, including refined coloratura as well as blazing dramatic power.

Jason: I totally agree. Though I’ve never heard Levine conduct this opera. Lulu (and Wozzeck) are two of Levine’s signature works, but the conductor was already in ill health back in 2010, the last time Lulu appeared here. He pulled out of that production too.

I’m hardly the first person to say that Levine’s refusal to retire is part of a larger crisis of leadership at the Met – the largest performing arts organisation in the United States, but one beset by financial and artistic hardships. Neither Levine nor Gelb seems to have what’s needed to turn the place around, and the Met doesn’t have an artistic director, someone who could make the company feel like the vital American and global institution it should be. And yet, every now and then, we get a night like last night’s Lulu: the sort of production that reminds you of opera’s unique power, and what can happen when music and theater and visual arts inform one another at the highest calibre.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion