| Opera Reviews | 19 April 2024 |

The Met's new Merry Widow needs to be merrierby Steve Cohen |

|

| Lehar: The Merry Widow Metropolitan Opera (HD simulcast) January 2015 |

|

|

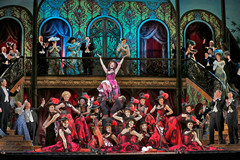

The Merry Widow is an echo of Vienna’s Imperial heyday, with nostalgia that should be crowd-pleasing. Since it has folk dances plus waltzes plus the can-can, it was appropriate to engage Broadway’s Susan Stroman to choreograph and direct the production. But her work here is sub-par compared to her many previous successes. Perhaps she was intimidated by the huge hall or the musical bureaucracy, but her work only came to life in the final act. Most of her cast seemed tentative too. I’ve seen productions of this operetta in Europe and the USA that were much simpler, less star-cast yet more enjoyable. The familiar story is set in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Paris, when the fictional nation of Pontevedro faces financial ruin because its wealthiest citizen, the widow Hanna Glawari, is in the French capital to find a husband and if she marries anyone but a Pontevedrian she will forfeit her inheritance and the country will go broke. Some observers blamed the lack of intimacy in the 3800-seat house, others criticized the translation and some faulted the casting of Renée Fleming. I put much of the onus on the operetta itself, although I’ve loved Lehar’s works for many years and enjoyed a pilgrimage to his home in Bad Ischl. Compare The Merry Widow, however, to the best works by Johann Strauss and Emmerich Kalman (such as Fledermaus and Countess Maritza) and Lehar’s piece is inferior. His predecessors constructed expansive musical sequences with great ensembles; Lehar did not. Strauss and Kalman wrote stage pieces that had drama and suspense as well as humor; The Merry Widow is predictable. It can still work, but it needs careful handling. Renée Fleming convincingly portrayed the haughty and wistful aspects of the millionairess but not her merriness, and her singing was awkwardly over-projected. The floating high B pianissimo at the end of the “Vilia” song was okay on an early radio broadcast but flat during the live radio-and-cinema simulcast. Even when she hit notes accurately, there was little shimmering frisson. Most of the role lies lower than the best part of Fleming’s voice. It has really a middle-soprano range, so it should sound better when the mezzo-soprano Susan Graham takes over the part after Fleming’s departure on January 31. Hanna’s long-ago lover, reluctant to get tied down, was the handsome Nathan Gunn, though his voice was less resplendent than in the past. The accomplished Broadway star Kelli O’Hara made the best impression of the night in her Met debut as Valencienne, the unfaithful wife of the ambassador who was well-played by the reliable Thomas Allen. Tenor Alek Shrader seemed out of his element. The comic embassy secretary Njegus was enacted as a stereotypical flaming queen even though the libretto indicates that the character lusts after women. This impersonation was as confusing as it was homophobic. There’s much too much talk; the libretto could have been cut considerably so we could get to the music which, after all, is what we care about. The plot is so cliché that audiences don’t need to have it spelled out. The best part of the production was the seamless transformation from Mme Glawari’s party to Maxim’s as Act 2 transitioned to Act 3 without a pause. Here Stroman let loose with dazzling dances and O’Hara was surpassingly agile when she joined the can-can.

|

|

| Text ©

Steve Cohen Photo © Ken Howard / Metropolitan Opera |

Die Lustige Witwe in an English translation looked as if it would be the big hit of this Metropolitan Opera season. But it disappointed me and many other critics. What went wrong?

Die Lustige Witwe in an English translation looked as if it would be the big hit of this Metropolitan Opera season. But it disappointed me and many other critics. What went wrong?