Walking in on a costumed rehearsal of a scene at New York’s Metropolitan Opera is a thrilling experience. It’s difficult not to feel a flash of energy in the house when you hear a conductor shouting urgently over the music as the orchestra plays, communicating an interpretive wish to a particular soloist. Meanwhile, you can hear different technical department-heads whispering into headsets — and see stagehands moving props around (while artfully weaving around the singers who are still learning how to hit their marks).

But the rehearsal I walk in on Wednesday – a scene from Alban Berg’s Lulu, in a new production by South African visual artist and director William Kentridge – is busier than any I’ve encountered previously. Massive, writhing video projections of Kentridge’s famed ink-on-paper, collage style illustrations overlay the presentation of this aesthetically sensuous and philosophically grim opera about a sexually voracious – and murderous – femme fatale. Kentridge’s images flutter in place, then blow away at precise intervals, recalibrating the physical set’s underlying art deco style every few seconds. The number of technicians in the aisles, on this occasion, seems approximately double the normal amount.

In the third-act scene under rehearsal, the ever-lusted-after Lulu is being blackmailed by multiple characters, one of whom, the vulgar Marquis, advertises coerced labour in his prostitution ring as an appealing alternative to jail. While soprano Marlis Petersen, an expert in the opera’s title role, stands on a chair to proclaim Lulu’s unsuitability for the gig, the actor playing the Marquis strides over the Met’s stage, and leans against a piano pulling duty as a stage prop.

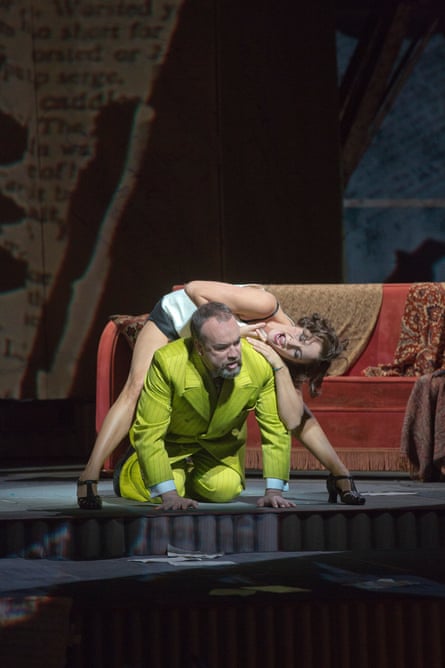

Improbably, a dancer’s leg emerges, pointing skyward. As he dismisses Lulu’s objections, the Marquis fondles the hamstring, while oozing an oily, entitled lasciviousness. The frenetic image-making and gently surreal mise en scene is classic Kentridge, a world away from the straightforward but effective John Dexter production that America’s largest opera house has been using for decades – that is, until the new Kentridge version takes over, next week. (A live broadcast of this production is scheduled for select cinemas around the world, on 21 November.)

A man bearing no headset strides in front of my view. I’m rather irritated, then recognise from his shock of pure white hair, that it’s Kentridge himself. For the next 15 minutes, he paces the stalls from one end of the house to the other, checking sight-lines until it’s lunchtime.

“It’s the first time we’re seeing this scene with video and lights,” Kentridge says, sitting down next to me. “We’re looking at wigs, costumes, lights, video and the orchestra – five elements that are coming together today for the first time, to see how it fits. And it’s really only here in the house, not in the rehearsal room, where you can say: ‘You can watch this scene,’ or ‘it’s impossible to watch it, there’s so much going on.’”

Kentridge seems pleased overall by “the great first scene of the third act: where money and sex come together. Blackmail and making money in the stock exchange – and losing it. Which feels so completely contemporary as a phenomenon.”

On an partial first impression, his strategy for presenting the gloomy grandeur of Berg’s late-Weimar aesthetic does look compelling. Whereas the trend in recent productions of Lulu has trended to porny explicitness – as with Krzysztof Warlikowski’s recent staging in Brussels – Kentridge seems to be charting a less cliched path to the opera’s famed luridness.

“It’s about saying: the object of desire doesn’t have to do with that first level of striptease and sexiness,” Kentridge tells me. “It has to do with all sorts of other things that trigger obsession: sometimes indifference on the part of the object of desire. That can be the most irresistible thing. What do you have to do to try to break through that barrier? So playing cold can be as obsessive-making and as desirous as playing hot.” Speaking of his work with Petersen, Kentridge says “we played with both of those elements, within her: when she’s in control of a situation – and is cooly being able to observe the growing infatuation of different men with her – to when she is unable to see herself.”

As with his house debut at the Met – a critical smash-hit production of Shostakovich’s absurdist opus The Nose – the director is relying on some favored techniques, in presenting a hyperactively visual version of Lulu. English subtitles, for example, will be projected at the base of the Met’s stage (in addition to the customary digital texts that the Met produces on the backs of each seat). The idea, Kentridge says, is to give audiences the option of “one area of focus,” allowing spectators to keep their eyes firmly fixed on the fast-moving stage art.

“The principle that we had in The Nose, of large-scale projections and singers in front of them – or integrated or separated from them – is the same here,” he notes. “But here the whole world is constructed by the projections. Which aren’t projections of scenery, but projections of thoughts and images, largely of people. Different images of Lulu, details of the men in her life.

“At the starting point,” he continues, “I knew they were going to be ink drawings. The pages were constructed out of four or eight or 16 sheets of paper that were collaged. [Each] drawing is not just stuck together … they’re painted as fragments and then the whole is constructed by placing these fragments on top of each other, to find the drawing. So that in itself suggested a kind of fragmentation of the object of desire: how do you hold ‘who Lulu is’ together? She’s there, and you hope she’s going to be this goddess, but she’s not.

This instability, he says, is a theme of the opera. “In operatic terms, instability is always represented by death: something can’t hold, you know there’s going to be a body on stage. And so in the drawings, there are these unstable sheets of paper that can blow apart, that can come together. It’s both a formal device to work with the music, but it also becomes one of the themes of the opera.”

It’s also clear that the director is interested in engaging with Berg’s fascinating and idiosyncratic score – one touched by both the language of Schoenberg’s 12-tone (or, if you like, “atonal”) method as well as late-Romantic lushness. To that end, Kentridge-the-filmmaker has actually followed Berg’s multimedia instruction to shoot a film to go with the palindromic, two-and-a-half-minute Act II interlude (which represents Lulu’s imprisonment, contraction of cholera, and subsequent escape).

The Met’s previous production of Lulu originally included a rather uninspiring series of line drawings – as opposed to Berg’s requested live-action film – and those drawings were omitted entirely during that production’s last revival, in 2010. By contrast, Kentridge’s film is a mini-masterpiece in and of itself. It respects the scenario scripted by Berg, while allowing for some poetic, noir-like smoky images beyond the composer’s imagining. (A few images of the interlude film can be seen in the Met’s trailer for this production.)

Critically, Kentridge’s version of the act two film refuses to fill in all the narrative lacunae that sit between the first and second halves of the opera. He retains the modernist abstraction that Berg seems to have desired, when cobbling together his narrative source material (that being the two different Lulu plays by Frank Wedekind: Earth Spirit and Pandora’s Box). Though by the time of his death, in 1935, Berg had only finished a short score to Lulu’s final act – the work is now performed with a version of the third act orchestrated by the composer Friedrich Cerha – Kentridge notes that the overall work is steeped in the experimentations of Berg’s time. “The 20s and 30s [were] the heyday of German experimental cinema,” he says. “I’m sure it was completely in the air: short, nonlinear experimental films. … I’m sure it’s kind of like having a telephone on set: let’s break with the usual things you expect to see in an opera.”

In that same spirit of breaking with convention, Kentridge says he’s walking into the final week of rehearsal with an open mind about the character of Lulu herself. As a few of the Met’s staffers gathered behind us, eager to have Kentridge’s opinion on the details yet to be decided upon, he told me: “We’ve got the particular talents and remarkable skill of Marlis Petersen. And at the end of the six weeks of rehearsal, we’ll see it on stage on the first night – and we’ll see what our Lulu is. It’s not as if we start with a Lulu and then just execute her.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion