Michael Billington, writing about Endgame in these pages a while ago, once used the phrase “the terrible music of Beckett’s prose” to describe the bitter beauty of the play’s language. In György Kurtág’s opera, the words retain their fierce, lacerating power, though the music extends a deep and ambivalent compassion to Beckett’s characters even as their rebarbative sparring masks fears of decline, isolation, endings and loss. This is not, in essence, the bleak comedy we often find, but a work of pervasive sadness that continues to haunt us after its final notes have died away.

Considered a masterpiece by many at its 2018 Milan premiere, Endgame (more correctly Fin de Partie, as Kurtág uses the French text) has now been given its first UK performance at the Proms by the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra under Ryan Wigglesworth, in a semi-staging by Victoria Newlyn. Playing and conducting, as one might expect, were superb. Wigglesworth dug deep into the score’s detail while maintaining the dramatic pressure throughout, and you couldn’t help but be struck both by Kurtág’s fastidious craftsmanship and the way every verbal and musical gesture tells, often through the sparest and simplest of means. Flaring brass suggested fury, futile or otherwise, and cimbalom taps quietly frayed the protagonists’ nerves. But there were also moments of quite extraordinary beauty, particularly as Nell (Hilary Summers) and Nagg (Leonardo Cortellazzi) lose themselves in memories of the past.

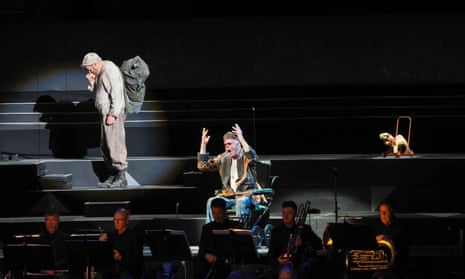

Newlyn, meanwhile, was faced with the unenviable task of having to stage the work in the vast space of the Albert Hall, where it’s difficult to suggest claustrophobia or indeed the dying, possibly post-apocalyptic natural world outside. By and large she succeeded with admirable clarity and great simplicity, positioning the singers on the steps and platforms behind and above the orchestra, with Morgan Moody’s Clov scuttling between Hamm (Frode Olsen), an imposing presence in his wheelchair, and Summers and Cortellazzi in their trash cans. Newlyn’s decision to use (sometimes flickering) videos of laughing faces, vaudeville posters and rippling waves (for Nell’s memories of Lake Como), projected on the screen running behind the players and singers, was a big distraction on occasion, but ultimately didn’t detract from some superb performances.

Both play and libretto allude to The Tempest, and Olsen raged at the encroaching solitude like some impotent Prospero faced with the loss of his powers, while Moody, a wonderful singing actor, bristled with resentment and unexpressed contempt. Summers and Cortellazzi, meanwhile, were both exceptional: she sounded ravishing in those memories of Lake Como: and his wail of misery when he realises she has died was unforgettable and almost unbearable.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion