With operas as storied as those composed by Mozart, it can sometimes be difficult to work through the crust of one’s personal expectations to find what’s funny and fresh about a centuries-old piece of art. The Magic Flute is fanciful and light and escapist; an opera of trials and tribulations and high priests and falling in love. This tone might not seem befitting of our current political landscape, but that’s perhaps precisely why the prospect of a new take on The Magic Flute, playing at Lincoln Center this week (for four nights only), feels so vitally ripe with possibility.

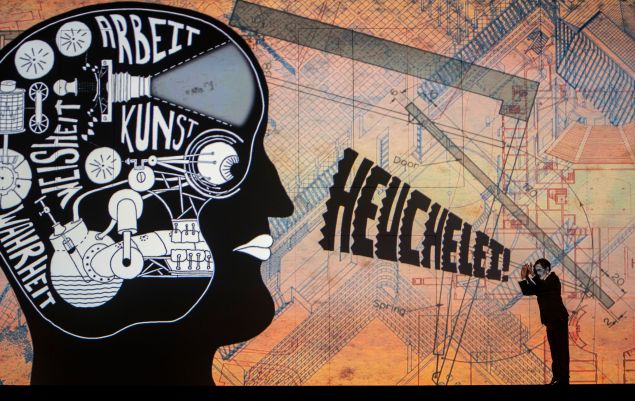

Directed by Barrie Kosky, overseen by the British theatre company 1927 and presented as part of the 2019 Mostly Mozart Festival, this Flute borrows its mood from the silent film Prohibition era—ecstatic emotionality rendered in starkly gorgeous tones—with a set made out of digital projection. Observer spoke to Ulrich Lenz, the show’s dramaturge, about how this production differs from its predecessors.

Observer: Could you take me through what’s involved with being a dramaturge?

Ulrich Lenz: A dramaturge is a person that mainly exists in German-speaking countries. Every German-speaking country has its own drama troupe or more than one drama troupe, and it’s a kind of intellectual advisor and organizer role that’s been present in the theatre since the 18th century and stayed until today.

It has nothing to do with writing a piece. In the Roman languages of Italian or Spanish, it would be the one who writes the play. But, in Germany, it means someone who is in the organization who leads the team, an advisor for the director of the piece, who accompanies the whole process of creating a new theatre production right from the beginning—from the first talk between the set designer and costume designer, the director and the musical director, until the premiere. [The dramaturge facilitates] the connection between the house and the artist, the connection between the audience and the house of the production. A lot of [a new production involves] introduction for the audience, explaining what we’ve done, what we’ve heard about it and what everyone can see in the program. That’s just a small part of my work.

Does it have to do with introducing people to the historical context of the show? I know for this version of The Magic Flute, you have placed it stylistically in the 1920s, with a sort of inflection of silent movie aesthetics. Was your work for this more involved around that period, or was it more for when The Magic Flute was first written and performed in the 1790s?

I think an artistic work is born in some time in a period of history, but the mystery of art is that it speaks to us even over 200 years. Everyone can discover something in the piece and learn about it, and that has nothing to do with just knowing the historical background—that’s interesting, but not necessary. That’s what makes the piece modern, that we can tell the story in our way.

I tried to avoid explaining everything. The historical part is not that important, more important is the thought of the production team and what is told in the story of The Magic Flute. For example, what is told about human beings, about love, about coming together, about the power of love, about the power of beauty. And of course, there is some detail about the historical background, why Mozart wrote it this way, not that way, but I would say a good production doesn’t really need an introduction to understand it. Introduction would help to understand it better, but if you need the introduction to understand it [at all], then it’s a bad production.

What’s a detail from this production that’s a personal favorite of yours?

I must admit that for a long time I hated The Magic Flute, because I found the story and plot a little silly, and I didn’t understand why the characters are going crazy. The story seems to me very simple, and it seems to jump from one side to another and seems not connected to each other. I discovered, working on this production, the secret of The Magic Flute. That is, you can’t interpret the characters as psychological characters. The non-logic of characters: you have to accept this, and if you accept this, then you can dive into it and you don’t have to worry about why he’s there not there, or is she the evil one or the good one; that’s the secret. There are a lot of things you can’t explain in this opera.

That’s my favorite [aspect] of this production—that I learned to accept the inner meaning of this story of the fairytale. There are many, many details that we created to help the story, and invent new images, like the cat, which we called Karl-Heinz, very German name, as the pet of Papageno, who catches birds like a cat does. But you wouldn’t ever “get” a certain character if you explained things. A whole lot of words wont explain what is immediately understood if you see a cat and a bird caught up together. [The cat is] a funny partner for a sad clown, because Papageno is telling 50 percent of the jokes in the play. He’s not really funny, to me—he tries to be funny. He’s the type of sad clown Buster Keaton was, so what’s much more funny and more human is his relations with the other people and his relationship with his cat. That’s the secret of The Magic Flute, that it works for an eight year old child and an eighty year old man, there’s something everyone can discover in this piece.